Mara Trübenbach

PERFORMING MATERIAL DRAMATURGY IN ARCHITECTURAL EDUCATION

PERFORMING MATERIAL DRAMATURGY IN ARCHITECTURAL EDUCATION

Key words

Embodied Knowledge, Emotion, Material Agency, Non-Representational Theory, Performativity, Sensory Engagement, Situated Knowledge

Abstract This visual contribution centers on a performance-lecture developed during my practice-based PhD, which explored material agency and sensory engagement in architectural practice. Using the lecture as a medium, I examine how performative techniques and material interactions illuminate the co-creative process between humans and materials. This approach highlights the importance of non-representational, sensory experiences in rethinking architectural design and knowledge production.

![]()

Preparing the Stage

In my practice-based PhD, I was interested in establishing a methodology in architectural practice that uses techniques one can see in the performing arts focusing on emotional awareness. One reason I brought architecture and theatre together was to consider what the experience of developing a story can teach the process of designing. In short, I was interested in the methods other practitioners—such as textile artists, costume designers, or scenographers—use when they work and interact with materials. My focus was on the agency of materials and the co-presence of humans and materials in the process of making architectural models, scenography and costumes, creating spaces of proximity and engagement.

What I did was to lay down an auto-ethnographic account of my situated knowledge. The aim was to introduce records that would otherwise remain outside architectural research and to make those accessible to others. I considered material not as a representative of something else but as a performative entity in which knowledge is embedded that we can learn from while working, engaging, or entering into dialogue with. This opened a transformative space, where the relationship with the material could therefore be positioned as dramaturgical means that reduces the distance between the creator and spectator.

![]()

Performing the Narrative

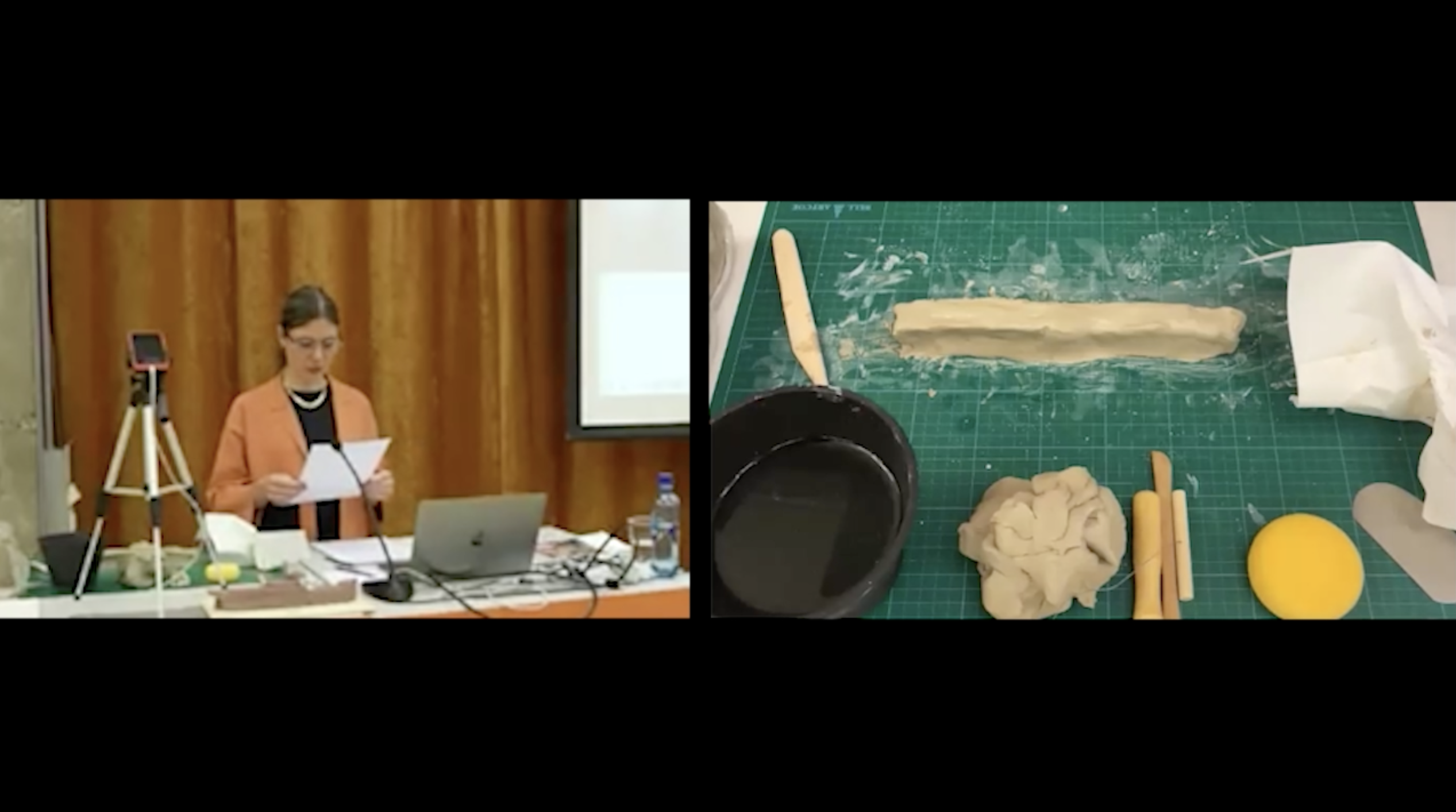

The trailer presented in this visual contribution is an excerpt from a performance-lecture developed as part of my PhD research. This approach was my response to the Oslo School of Architecture and Design's requirement for PhD candidates to deliver a trial lecture on the day of their public defense (fig. 1). Two weeks before my disputation, the committee assigned me the title for my lecture: 'Performing Material Dramaturgy in Architectural Education: A Demonstration Lecture.’ In my response, I worked with clay, modeling, and a pre-recorded voiceover, using the lecture format itself as a medium for animating material—thinking quite literally with my hands. By disrupting the conventional structure of a lecture, I created a space that was both playful and hybrid, offering a form of participation that made making a model an act of engagement with materials (fig. 2). As Cérèzo states, “the form of the performance-lecture enables an ongoing interplay between theory and practice, between the thinking and the making and between the making and reflection.” This interplay is at the heart of what the performance lecture does—where the boundaries between theory and practice blur, allowing material to “speak” and co-design with us.

![]()

Reflecting on Material Agency

But why is it interesting to capture the moment of what I experienced? It is impossible to translate into language the attention and tactility of the sensed moment. By integrating performative techniques, such as improvisational modeling and staged interactions, I aimed to blur the boundaries between architectural practice and the performing arts. The body's role in this process was crucial, serving as a mediator between the human experience and material agency. This embodied approach provided new insights into the emotional and sensory dimensions of material interaction. For this, I see the architect’s body as a relational entity that helps to connect with the surroundings. Making these personal internalizations accessible by taking material seriously in its ability to awaken emotions through our sensing enables other modes of communication to the outside. In 1988, Donna Haraway questioned the notion of site by way of her concept of “situated knowledges” and critiqued the privilege of the insider perspective as a matter of power rather than truth. Following this critique, I invite thinking about other kinds of mediation of knowledge in architectural practice, which are non-representational and event-based.

![]()

To grapple with the questions of the relation between knowing and sensing to perform material dramaturgy, I draw on non-representational theory. This theory focuses on processes of becoming where much happens before and after conscious reflexive thought, emphasizing affects (inter-relational) and emotions (personal). It offers a critical lens for understanding the relational dynamics between humans and materials. This framework emphasizes the importance of affective experiences and the continuous process of becoming, which informed both the methodology and the interpretation of results. I argue, in architecture, the interaction of body, perception, and material forms a loop that feeds back into how we understand material.

Inspired by Stenger’s concept of ‘ecology of practices,’ my research reimagines the role of materials as co-creators, challenging traditional hierarchies and inviting us to reconsider the dynamics between humans and materials (fig. 3). By embracing the co-creative potential of humans and materials, I can recognize limits and push boundaries, opening up new dimensions of knowledge in architecture. By fostering sensory and emotional engagement, ‘material dramaturgy’ promotes non-anthropocentric ways of knowing. Integrating such approaches into design studios or workshops could, for instance, encourage architectural students to experience materials as active participants, enriching their understanding of the environment and the impact of materials on their decision-making moments in the design process.

![]()

Conclusion

This visual contribution reflects on the multifaceted dimensions of architectural knowledge, particularly how non-representational, performative, and emotional aspects enrich our understanding of architectural design. The exploration of ‘material dramaturgy’ underscores the importance of sensory and emotional engagement, bridging the gap between theoretical constructs and practical applications. As Frichot suggests, “Crucially, these limits or borders should not only be used as a line of defense, but rather a generous threshold of exploration, a reaching out, an experimental groping.” This open stance enables a deeper inquiry into the emotional and relational aspects of architectural practice. It challenges traditional notions of authorship and control in architecture, promoting a more collaborative, process-oriented approach in knowledge production.

Key words

Embodied Knowledge, Emotion, Material Agency, Non-Representational Theory, Performativity, Sensory Engagement, Situated Knowledge

Abstract This visual contribution centers on a performance-lecture developed during my practice-based PhD, which explored material agency and sensory engagement in architectural practice. Using the lecture as a medium, I examine how performative techniques and material interactions illuminate the co-creative process between humans and materials. This approach highlights the importance of non-representational, sensory experiences in rethinking architectural design and knowledge production.

Preparing the Stage

In my practice-based PhD, I was interested in establishing a methodology in architectural practice that uses techniques one can see in the performing arts focusing on emotional awareness. One reason I brought architecture and theatre together was to consider what the experience of developing a story can teach the process of designing. In short, I was interested in the methods other practitioners—such as textile artists, costume designers, or scenographers—use when they work and interact with materials. My focus was on the agency of materials and the co-presence of humans and materials in the process of making architectural models, scenography and costumes, creating spaces of proximity and engagement.

What I did was to lay down an auto-ethnographic account of my situated knowledge. The aim was to introduce records that would otherwise remain outside architectural research and to make those accessible to others. I considered material not as a representative of something else but as a performative entity in which knowledge is embedded that we can learn from while working, engaging, or entering into dialogue with. This opened a transformative space, where the relationship with the material could therefore be positioned as dramaturgical means that reduces the distance between the creator and spectator.

Performing the Narrative

The trailer presented in this visual contribution is an excerpt from a performance-lecture developed as part of my PhD research. This approach was my response to the Oslo School of Architecture and Design's requirement for PhD candidates to deliver a trial lecture on the day of their public defense (fig. 1). Two weeks before my disputation, the committee assigned me the title for my lecture: 'Performing Material Dramaturgy in Architectural Education: A Demonstration Lecture.’ In my response, I worked with clay, modeling, and a pre-recorded voiceover, using the lecture format itself as a medium for animating material—thinking quite literally with my hands. By disrupting the conventional structure of a lecture, I created a space that was both playful and hybrid, offering a form of participation that made making a model an act of engagement with materials (fig. 2). As Cérèzo states, “the form of the performance-lecture enables an ongoing interplay between theory and practice, between the thinking and the making and between the making and reflection.” This interplay is at the heart of what the performance lecture does—where the boundaries between theory and practice blur, allowing material to “speak” and co-design with us.

Reflecting on Material Agency

But why is it interesting to capture the moment of what I experienced? It is impossible to translate into language the attention and tactility of the sensed moment. By integrating performative techniques, such as improvisational modeling and staged interactions, I aimed to blur the boundaries between architectural practice and the performing arts. The body's role in this process was crucial, serving as a mediator between the human experience and material agency. This embodied approach provided new insights into the emotional and sensory dimensions of material interaction. For this, I see the architect’s body as a relational entity that helps to connect with the surroundings. Making these personal internalizations accessible by taking material seriously in its ability to awaken emotions through our sensing enables other modes of communication to the outside. In 1988, Donna Haraway questioned the notion of site by way of her concept of “situated knowledges” and critiqued the privilege of the insider perspective as a matter of power rather than truth. Following this critique, I invite thinking about other kinds of mediation of knowledge in architectural practice, which are non-representational and event-based.

To grapple with the questions of the relation between knowing and sensing to perform material dramaturgy, I draw on non-representational theory. This theory focuses on processes of becoming where much happens before and after conscious reflexive thought, emphasizing affects (inter-relational) and emotions (personal). It offers a critical lens for understanding the relational dynamics between humans and materials. This framework emphasizes the importance of affective experiences and the continuous process of becoming, which informed both the methodology and the interpretation of results. I argue, in architecture, the interaction of body, perception, and material forms a loop that feeds back into how we understand material.

Inspired by Stenger’s concept of ‘ecology of practices,’ my research reimagines the role of materials as co-creators, challenging traditional hierarchies and inviting us to reconsider the dynamics between humans and materials (fig. 3). By embracing the co-creative potential of humans and materials, I can recognize limits and push boundaries, opening up new dimensions of knowledge in architecture. By fostering sensory and emotional engagement, ‘material dramaturgy’ promotes non-anthropocentric ways of knowing. Integrating such approaches into design studios or workshops could, for instance, encourage architectural students to experience materials as active participants, enriching their understanding of the environment and the impact of materials on their decision-making moments in the design process.

Conclusion

This visual contribution reflects on the multifaceted dimensions of architectural knowledge, particularly how non-representational, performative, and emotional aspects enrich our understanding of architectural design. The exploration of ‘material dramaturgy’ underscores the importance of sensory and emotional engagement, bridging the gap between theoretical constructs and practical applications. As Frichot suggests, “Crucially, these limits or borders should not only be used as a line of defense, but rather a generous threshold of exploration, a reaching out, an experimental groping.” This open stance enables a deeper inquiry into the emotional and relational aspects of architectural practice. It challenges traditional notions of authorship and control in architecture, promoting a more collaborative, process-oriented approach in knowledge production.

Download Essay Here

Images and Figures Here