DONATE

Please help The Hoosac Institute grow our vibrant and engaging initiatives! No contribution is too small. The Hoosac Institute is a sponsored project of Fractured Atlas, a non-profit arts service organization. Thank you for your support!

Please help The Hoosac Institute grow our vibrant and engaging initiatives! No contribution is too small. The Hoosac Institute is a sponsored project of Fractured Atlas, a non-profit arts service organization. Thank you for your support!

#avoidance

#book

#breakup

#california

#care

THE HOOSAC INSTITUTE

The Hoosac Institute is a curated platform for text and image focusing on pieces that don’t fit conventional disciplinary narratives.

MISSION

Despite language expounding the necessity of experimentation, creativity, and interdisciplinarity, too many institutions keep their textual and image boundaries tightly controlled. We have all written, produced, or created projects that didn’t find a home; projects to which we devoted time, energy and skill. The Hoosac Institute dedicates itself to these very works of people whose titles may not reveal everything about themselves and their productive capacities.

HISTORY

Founded in 1970 in Williamstown, Massachusetts, The Hoosac Institute was dormant for nearly 50 years. The Institute was revived and restored in 2018 by Jenny Perlin in an effort to open drawers, shine lights, and reshuffle categories. The Hoosac itself is a river that runs through Massachusetts, Vermont, and New York. Its name can be translated from the Algonquian to either “the beyond place” or “the stony place.” Either one suits the founder fine.

— Jenny Perlin

Director, The Hoosac Institute

All names linked to their journal contributions

A. S. HAMRAH

ABIGAIL CHILD

ABOU FARMAN

ALEJANDRO CESARCO

ALINA STEFANESCU

ALINA TENSER

ALISSA QUART

ALIX PEARLSTEIN

AMY KAO

AN-MY LÊ

ANDREA RAY

ANDREW HIBBARD

ANDREW INGALL

ANDY GRAYDON

ANGELA WASHKO AND JESSE STILES

ANNA CRAYCROFT

ANNA FAROQHI

ANNA TALARICO

ANTHONY BANUA-SIMON

ANTHONY ELMS

ANTHONY GRAVES

ANTHONY HUBERMAN

ASSAF EVRON

ASTRIA SUPARAK

BARBARA HAMMER

BASIM MAGDY

BIBI CALDERARO

BILL BRAND

BIRGIT RATHSMANN AND RICK KARR

BRANDEN KOCH

BRENDAN FERNANDES

BRIAY CONDITT

BRIAN FRYE

BRIAN FUATA

BROOKE SINGER

CARLA DELLA BEFFA

CARLOS GAMEZ

CARLOS MOTTA, KORAY DUMAN, THEODORE (TED) KERR

CAROL BECKER

CAROLEE SCHNEEMANN / RACHEL CHURNER

CELINA SU

CHARLES BERNSTEIN

CHELSEA KNIGHT AND NEAL WILSON

CHELSEA SPENGEMANN

CHRIS SULLIVAN

CHRISTIAN GRÜNY

CHRISTINA BATTLE

CHRISTINA MCPHEE

CHRISTINE HUME

CHRISTINE REBET

CLAIRE BARLIANT

CLAUDIA HART

CRAIG BALDWIN

CRISTÓBAL LEHYT

DAVID C. PORTER

DAVID HARTT

DAVID SCHAFER

DEBORAH LIGORIO

DEBORAH STRATMAN

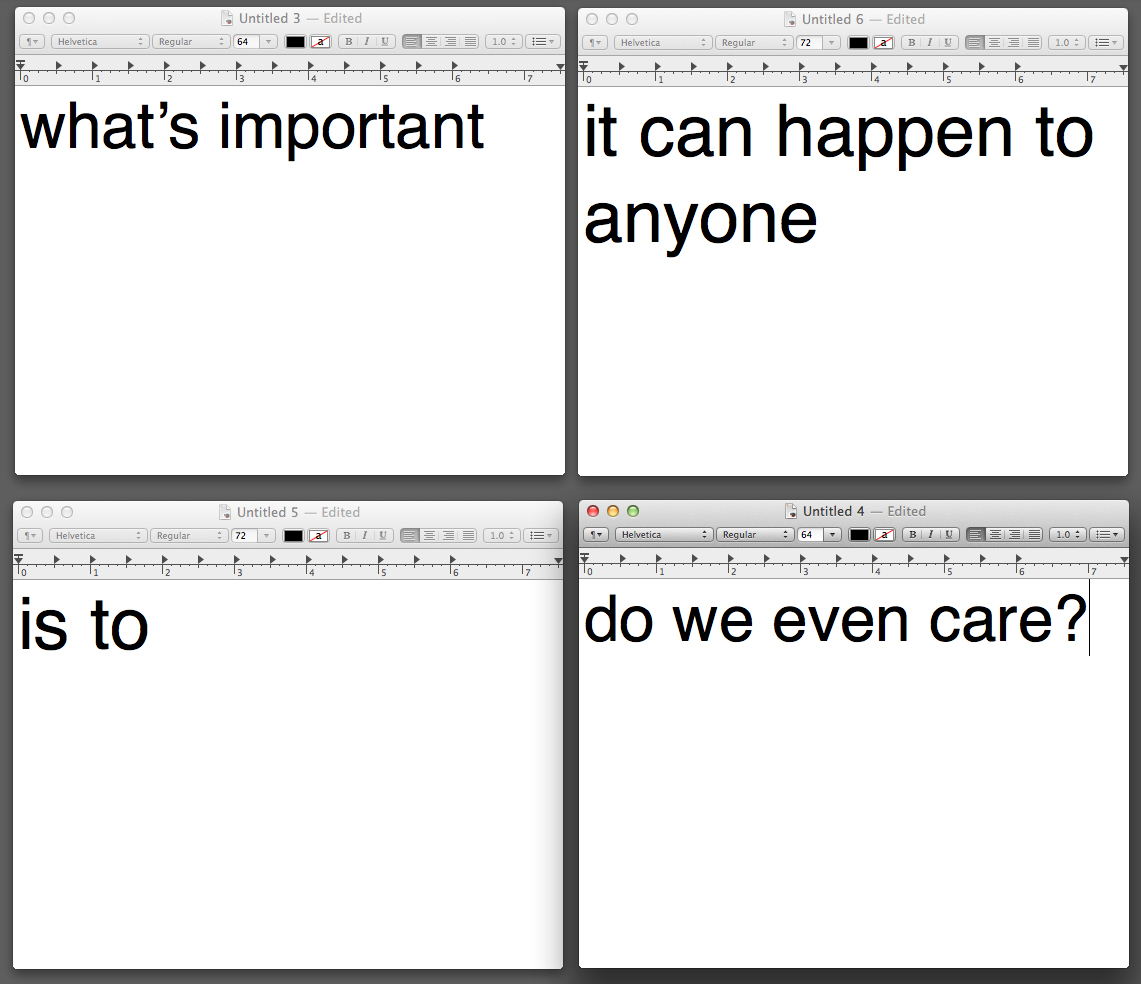

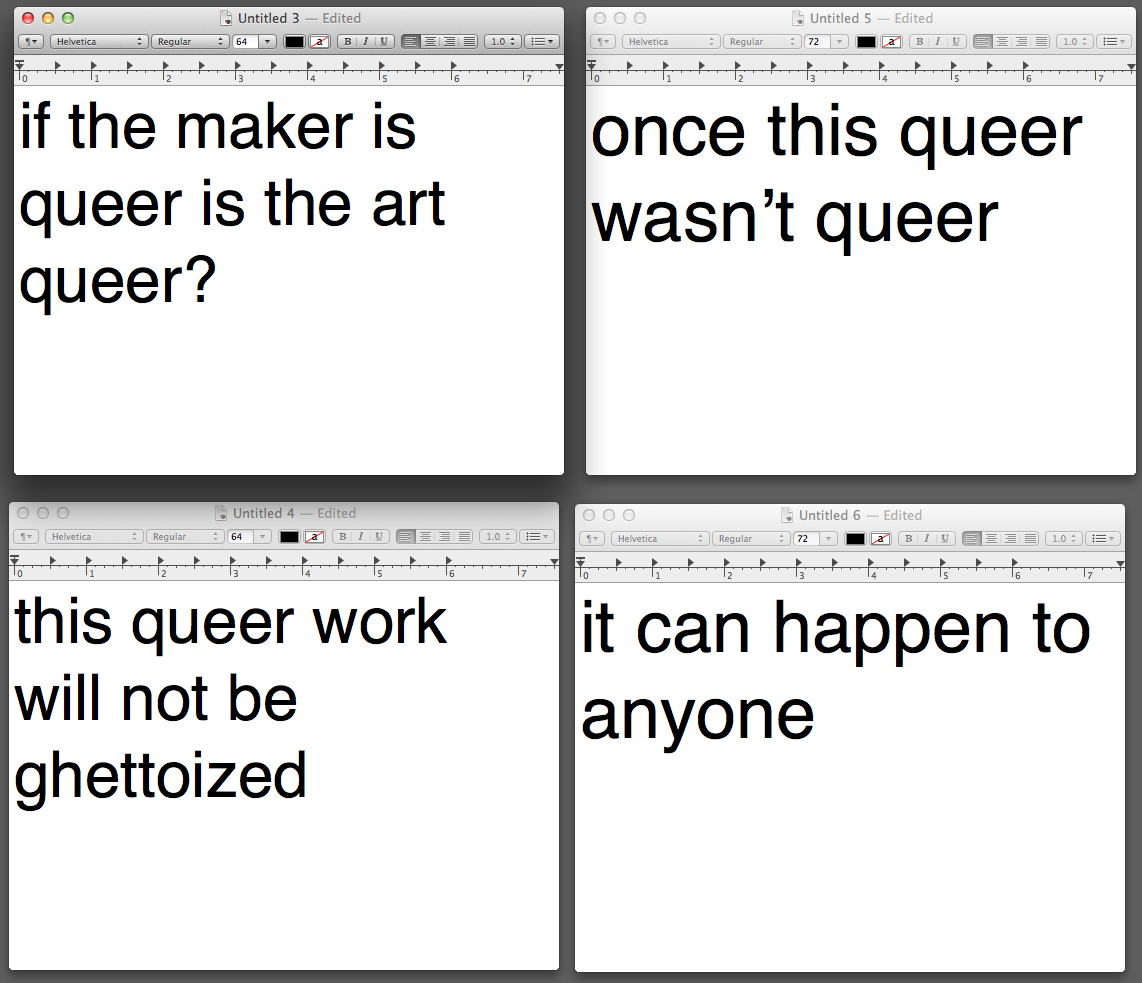

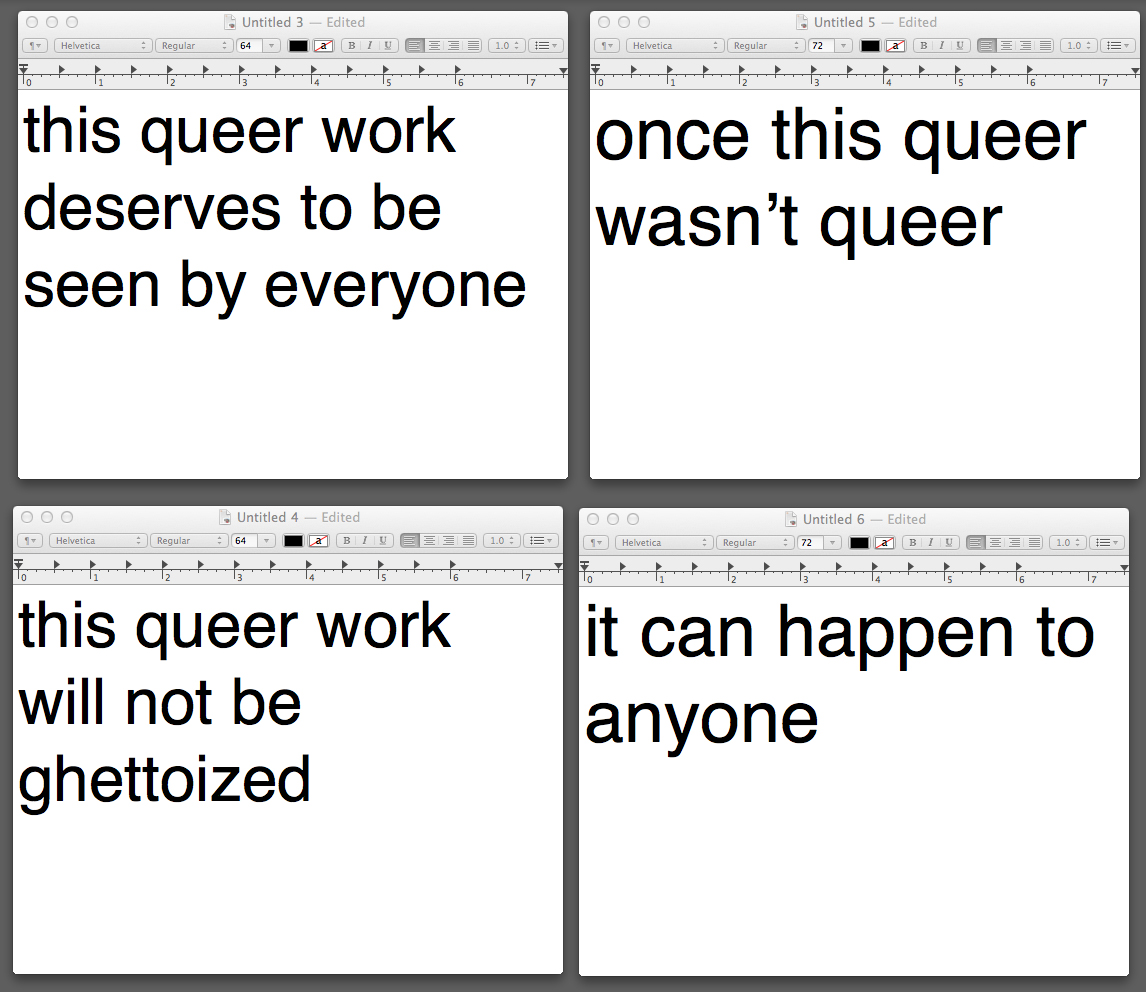

DISCOTECA FLAMING STAR

DORIS DUHENNOIS

DREAD SCOTT

DUBRAVKA SEKULIC

EDGAR ARCENEAUX

EKREM SERDAR

ELI HILL

ELIZABETH BOTTEN

ELLEN HARVEY

ELLEN ROTHENBERG

ELLIE GA

EMILY STEWART

ENRIQUE RAMIREZ

ENRIQUE ROURA PEREZ

ERICA BAUM

EVA STENRAM

FRANK CARLBERG

GABE CARBONARA

GABO CAMNITZER

GEORGE BAKER

GIANCARLO NORESE

GRETA BYRUM AND ANNABEL DAOU

HANS SCHABUS

HEATHER RASMUSSEN

HEIDE FASNACHT

HIND MEZAINA

HOMAY KING

HONG-KAI WANG WITH BOPHA CHHAY

HOPE GINSBURG, MATT FLOWERS, JOSHUA QUARLES

INSTAGRAMACUS

ITZIAR BARRIO

IURY SALUSTIANO TROJABORG

JAMIE ATHERTON

JAN BARACZ

JANICE GUY

JASON CHARNEY

JANE IRISH

JEANNE LIOTTA

JEN LIU

JENNIFER GERSTEN

JENNIFER REEVES

JENNY POLAK

JENNY YURSHANSKY

JESSICA BARDSLEY

JESSICA MEIN

JESSE ASH

JILL MAGID

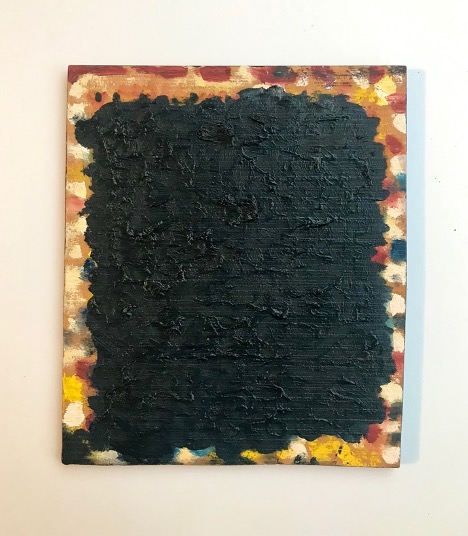

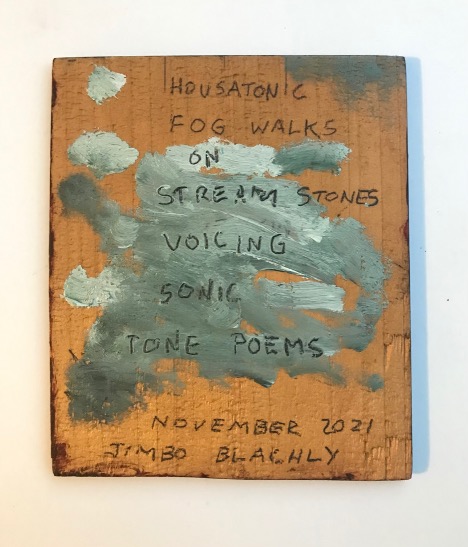

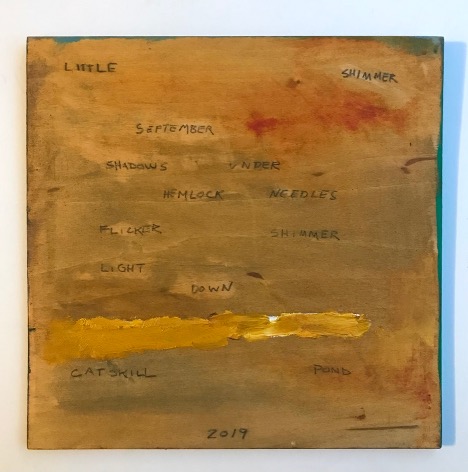

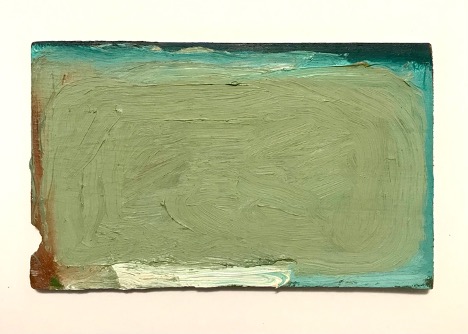

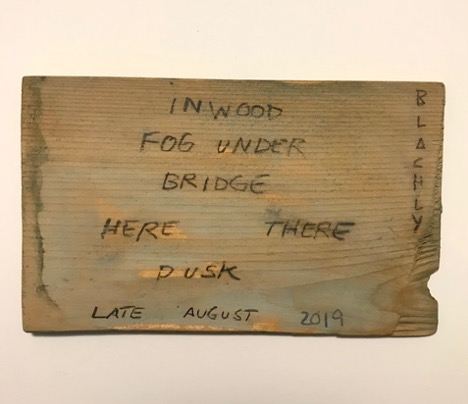

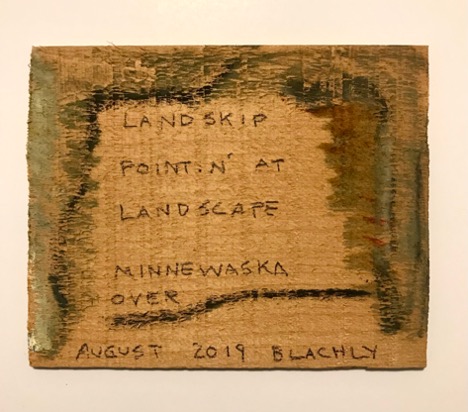

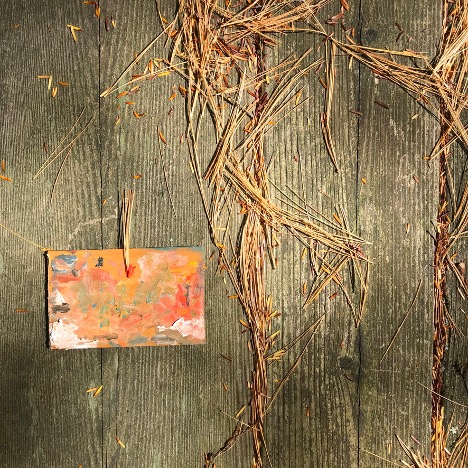

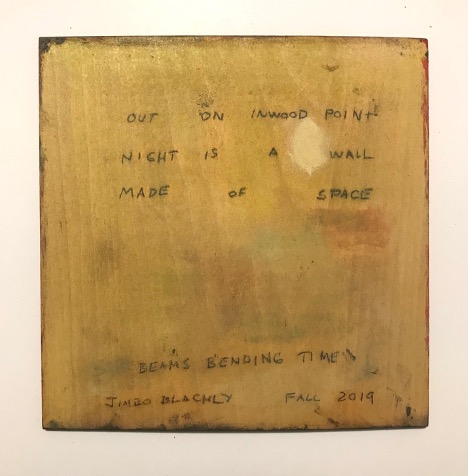

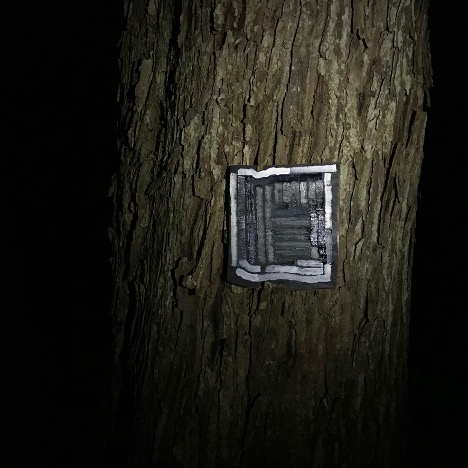

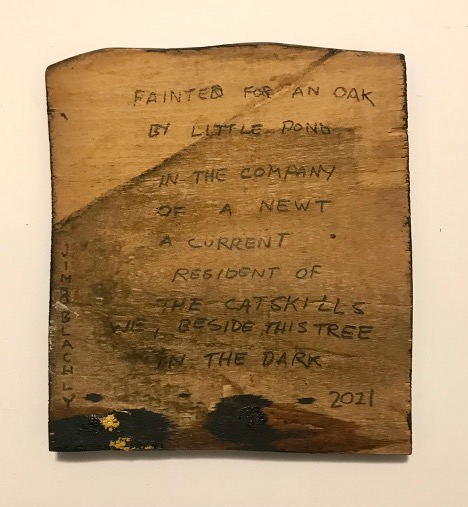

JIMBO BLACHLY

JOHN G. HANHARDT

JOHN GUTMANN

JOHN PILSON

JON DAVIES

JULIA PAULL

JULIAN HOEBER

JULIAN MAYFIELD

JULIET KOSS

JULIO GRINBLATT

JUSTIN BLINDER

JUSTINE LAI

KAREN YASINSKY

KATHERINE BEHAR

KEITH WALDROP

KENNETH TAM

KERRY TRIBE

KEVIN MOORE

KOAN ANNE BRINK

LARISSA HARRIS

LAURA LARSON

LAURA PARNES

LEE ARNOLD

LIBI ROSE STRIEGL

LINDSAY PACKER

LISA TAN

LJ ROBERTS

LOUISE BOURQUE

LUBA DROZD

LUCY SANTE

LUIS CAMNITZER

LYNNE SACHS

MADELINE DJEREJIAN

MAI-LIN CHENG

MARA TRÜBENBACH

MARIANGELES SOTO-DIAZ

MARIA PALACIOS CRUZ

MARIUS MOLDVÆR

MARJANA KRAJAC

MARISSA BLUESTONE

MARY LUM

MARY MANNING

MARY SIMPSON

MATHILDE BONNEFOY

MELINDA RICE

MELISSA GORDON

MICHAEL BLUM

MICHELLE ROSENBERG

MICHELE ALPERN

MICHY MARXUACH

MIRA SCHOR

MIRIAM SIMUN AND DEDE

NADIA HIRONAKA & MATTHEW SUIB

NAEEM MOHAIEMEN

NAOMI ROHATYN

NELSON SANTOS

NELL IRVIN PAINTER

NELL PAINTER

NIAMH O’MALLEY

NINA KATCHADOURIAN

NINA MENKES

NORI PAO

OLAV WESTPHALEN

PABLO HELGUERA

PAIGE K. BRADLEY

PAUL MCDEVITT AND LUKE DOWD

PAULINE GLOSS

PAREESA POURIAN

PATTY CHANG

PETER ROSE

PETRINE VINJE

RACHEL STEVENS

RACHEL URKOWITZ

REA TAJIRI

REBECCA BELL

REGINE BASHA

RIA BANERJEE

RICHARD BLOES

ROBEL TEMESGEN

ROSALIND NASHASHIBI

ROSMARIE WALDROP

ROYDEN WATSON

SAISHA GRAYSON

SAM ROSNER

SARA MAGENHEIMER

SARA VANDERBEEK

SARAH JANE LAPP

SARAH RUHL

SARAH TORTORA

SELBY HICKEY

SHEILA PEPE

SHELLY SILVER

SHOSHANA DENTZ

SNOW YUNXUE FU

SO MAYER

SOFIA LOMBA

SOPHIE TOTTIE

STANYA KAHN

STÉPHANIE SAADÉ

SUSAN BEE

SUSAN DAITCH

SUSAN JAHODA AND ROBERT BLAKE

SUSETTE MIN

SUZANNE SILVER

T. KIM-TRANG TRAN

TATIANA ISTOMINA

TAVI MERAUD

TERENCE GOWER

TERESITA FERNANDEZ AND JOSH FRANCO

TERRY PERLIN

THOMAS DEVANEY AND RAINY ORTECA

TONY BLUESTONE

TRINH T. MINH-HA

TYLER COBURN

ULRIKE MÜLLER

UMBER MAJEED

VALERIE TEVERE AND ANGEL NEVAREZ

YANE CALOVSKI

YEVGENIYA BARAS

ZELJKA BLASIC AKA GITA BLAK

ZOE BELOFF

The Hoosac Institute presents

RENEW

An occasional event series.

Anna Faroqhi & Haim Peretz;

discoteca flaming star

EVENT #7

Live from BERLIN!

Thursday, January 28, 2021

19.00 Berlin time/12pm EST/9am PST

Video + conversations about care, sustenance, collaboration and mutual aid. Anna Faroqhi and Haim Peretz in conversation with discoteca flaming star (and vice versa).

Anna Faroqhi & Haim Peretz are artists and authors of experimental and documentary films. They have been working together since 2003, both as a team and in individual projects. Faroqhi is also an author of graphic novels. As a team, they create films, design exhibitions,and are interested in participatory forms of creation.

Frequent recurring themes are life in big cities, migration, and lifelong learning. Faroqhi and Peretz teach video at the Hochschule für Musik "Hanns Eisler" Berlin.

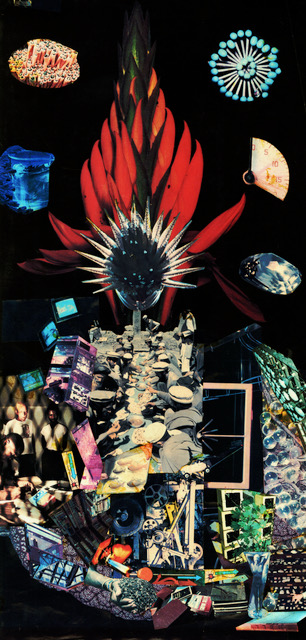

discoteca flaming star is an interdisciplinary collaborative art group, a group of people who use songs and other forms of oral expression, understanding them as a personal response to historical events and social and political facts. Through conceptual, visual and musical transfers, they create performances, sculptures, drawings, stages and situations whose foremost intentionis to question and challenge the memory of the public, transforming old desires and finding invented pasts, or pasts which never occurred. DFS is the place where the oracle speaks through the non-chosen. DFS is a love letter written in the present continuous, a love letter to thousands of artists.

discoteca flaming star is an interdisciplinary collaborative art group, a group of people who use songs and other forms of oral expression, understanding them as a personal response to historical events and social and political facts. Through conceptual, visual and musical transfers, they create performances, sculptures, drawings, stages and situations whose foremost intentionis to question and challenge the memory of the public, transforming old desires and finding invented pasts, or pasts which never occurred. DFS is the place where the oracle speaks through the non-chosen. DFS is a love letter written in the present continuous, a love letter to thousands of artists.

Past Events

SERIES: Renew

Anna Faroqhi & Haim Peretz; discoteca flaming star

January 28, 2021

link to conversation

SERIES: Escape

Laura Larson, Christine Hume, and others

December 2, 2020

link to performance

link to conversation

SERIES: Escape

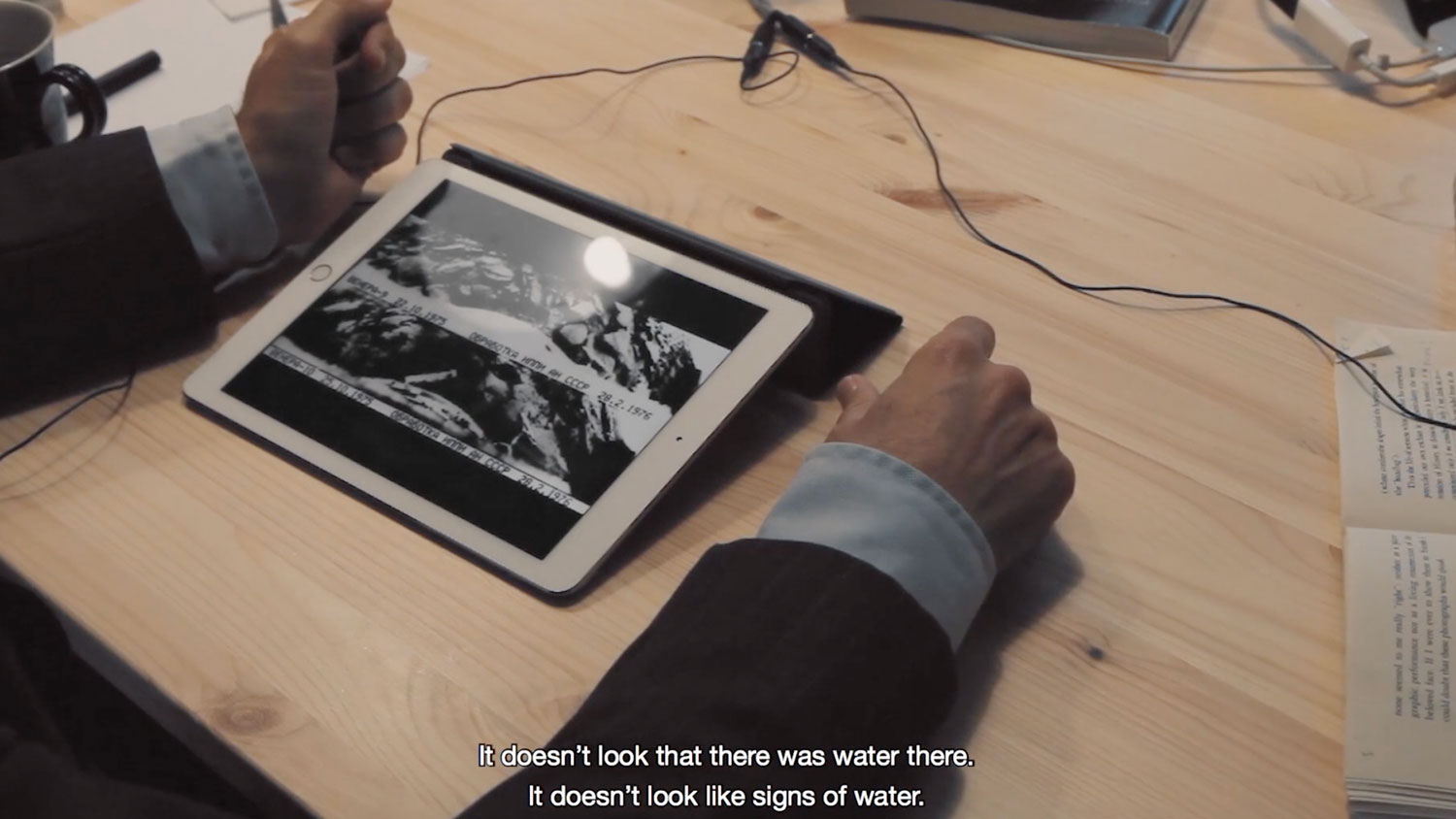

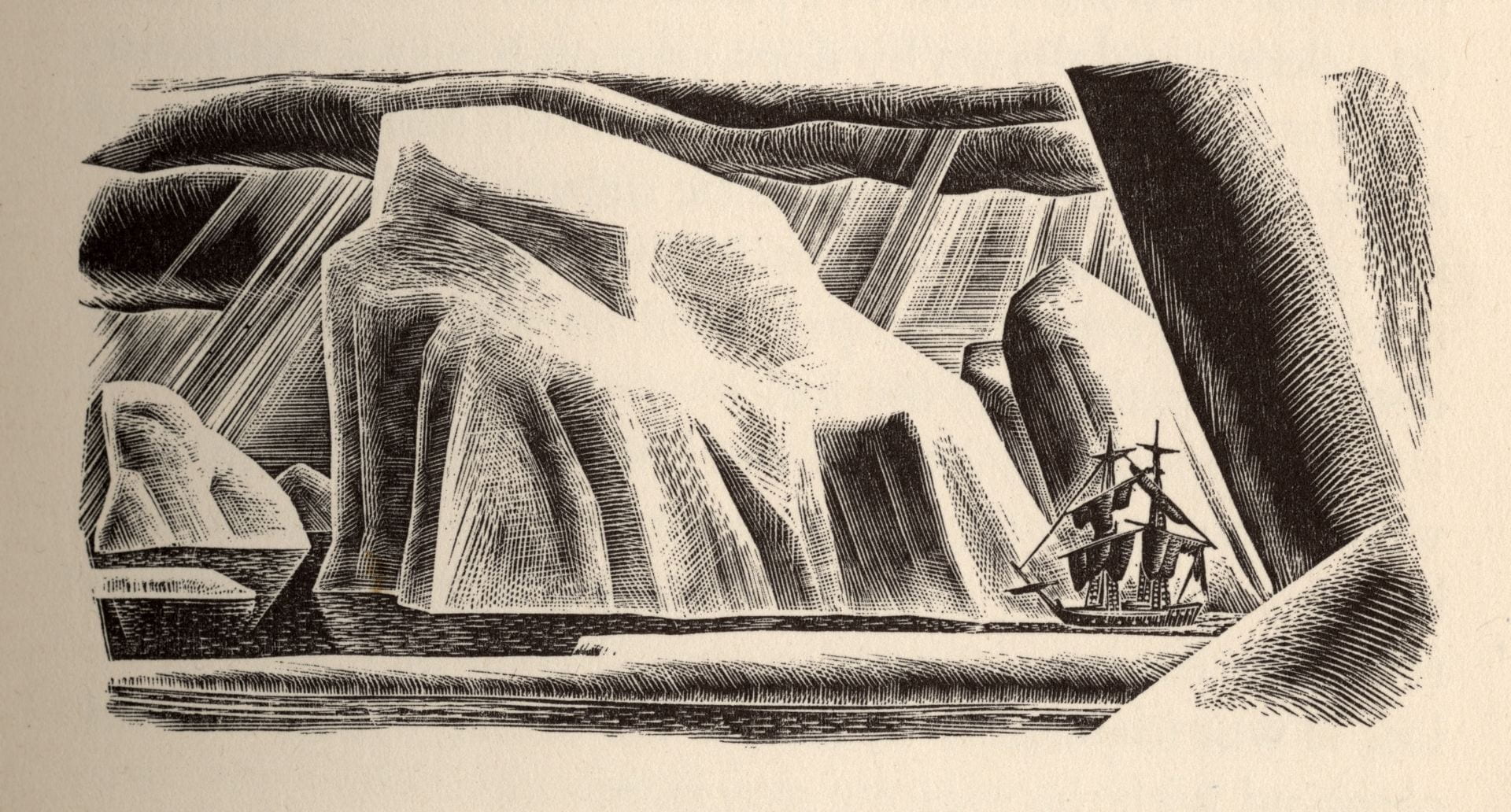

Ellie Ga and Lisa Tan

October 28, 2020

SERIES: Escape

Josh T Franco and Adan De La Garza

September 2, 2020

SERIES: Escape

Brian Fuata and Matthew Lyons

August 26, 2020

SERIES: Escape

Claire Barliant and Elizabeth Phelps Meyer

August 14, 2020

DONATE

Please help The Hoosac Institute grow our vibrant and engaging initiatives! No contribution is too small. The Hoosac Institute is a sponsored project of Fractured Atlas, a non-profit arts service organization. Thank you for your support!

Please help The Hoosac Institute grow our vibrant and engaging initiatives! No contribution is too small. The Hoosac Institute is a sponsored project of Fractured Atlas, a non-profit arts service organization. Thank you for your support!

Anthony Huberman

Eine-Machine.mp3

Fran-and-me.mp3

Here are two pieces of electronic music I made in....2001.

I remember it was a few months before 9/11. I would stay up really late and make loops!

Enrique Roura Perez

Our Common Shapes

Our Common Shapes unfolds as a moving archive—a video-based catalogue that animates a growing collection of sculptural casts made from single-use plastic packaging. Each form, cast in pigmented plaster, appears as both artifact and echo—an intimate fossil of contemporary life. The photographic documentation reveals the tactile qualities of these objects—their surfaces, shadows, and subtle imperfections—inviting a contemplative encounter with the ordinary.

The sequence transforms plastic fragments into symbols of collective memory, exposing how design, consumption, and material culture intertwine. This digital chapter expands the project’s sculptural logic into the virtual realm, where the objects circulate freely, detached from scale and function—reflecting on the mutable relationship between form, context, and meaning.

--enrique eduardo roura perez

Jennifer Gersten

Artist-in-Residence

Some years ago I was living in an old mansion on the other side of the city. A wealthy couple needed an attendant in exchange for free lodging, as the person who occupied the post was moving overseas. The house was six immense floors if you included the attic and basement apartment and contained, at any given turn, a cabinet heaving with silver, birthday wishes from some commander-in-chief, an armored safety deposit box braced for the end of civilization. In the dining room there hung a tentacular gold chandelier strewn with dried hyacinths that struck me as the stuff of myth, like a god frozen mid-metamorphosis. The back of the house featured a courtyard with a spiral staircase from which you could rubberneck onto the courtyards down the rest of the block, including the basketball-playing teenager two doors down whose dribbling, I would later learn, comprised the neighborhood ostinato.

My duties included occasionally vacuuming, though the couple’s ancient objects, many of which were truly ancient, made more sense to me covered in dust; if anything, I should have let myself collect dust in order to fit in. The most onerous of these tasks was watering their twenty or so plants, not a few of which lightened my burden by dying immediately after falling into my care. Because the owners were often traveling, the house was mostly mine. I had the idea that the owners were too accustomed to their money to even realize what sort of deal we had made in exchange for doing almost nothing.

About a year into my residency, the couple left. What started as a family vacation had been engulfed by an international emergency. In the interim, the couple said I could stay. I would be allowed to live there by myself, free of obligation, while the world sorted itself out. Suddenly I could set up on any of five floors in this house at the city’s heart and practice the violin—my profession, under less catastrophic circumstances—unseen and unheard, a fabulous privilege.

Within a few days, however, the situation already felt ridiculous. I practiced at a pulverizing volume, walking between the fifteen sumptuous rooms, playing something different in each one, playing not even for the sake of getting better, but just because I could. Long after I left a room, I imagined the sounds still lingering: sonatas swinging from the chandeliers, scales slithering into my bed.

When the owners told me they were finally on their way back and that I’d need to leave, I planned my move gladly. My need to fill up all the empty space had become compulsive, and I thought I could use a place with fewer floors, more boundaries. That very night, I started my search for a place where I wouldn’t be living alone, and found my roommate Lucy. I’m listening to her now. On the other side of our shared wall, the show she is watching has been proceeding in the same fashion for some time. Someone yells, someone else yells back, there is a crash or a clink, then there is a long stretch of mumbling, then the yelling restarts. I cannot hear exactly what they are yelling or why, but from the diversity of voices I can at least report that everyone on the show is getting a fair chance to express themselves.

I’d ask her what she’s watching, but she made clear from the outset her disdain for my questions. We met on a housing website for young people, where her profile was among the few not claiming to enforce an “intentional household,” implying authoritarian rule by vegans. In our first messages to each other, she said that she was a floral designer professionally, but upon moving in I discovered that the apartment plants were starting to plan their own funerals, which I guess is a sort of work-life balance. She was dismissive of my enthusiasm, and I was starting to suspect we might not be a good match. But when she said she didn’t mind that I was a musician who needed to make substantial noise on a regular basis, I thought about getting her name tattooed. This I reconsidered on the day that I moved in, when she dropped my key out the window by way of greeting and withdrew for the rest of the night. I lugged my boxes inside and opened the door to find her cats darting in and out of her room like panicked nurses. They still scramble if I come close, as does Lucy.

At Lucy’s, I remembered that closer the quarters you keep with strangers, the more you have to keep up the pantomime of privacy. At first I was alarmed by her reluctance, sometimes even her refusal, to respond to anything I said or asked, or how her calculations to avoid ever making eye contact could launch the next space mission. But now I have learned the drill. If one of us sees the other approaching, the other averts her eyes. If one is in her room, the other pretends she did not see limbs flashing behind the cracked door. This is the footnote to all small shared spaces, that they are even smaller if you take into account everything you are trying not to notice.

This tendency of hers was what ultimately made Lucy the perfect roommate. The violin is the instrument that, perhaps above any other, demands an early start on account of how long it takes to become even remotely proficient. The novitiate’s squeaks and scratches are easier on the ears when the novitiate is also cute, less so when she is paying her own taxes. You cannot let on to a musician that you can hear them working without firing their apology reflex, though there is nothing they can do about the state of affairs. Mention that you have enjoyed the sound of practicing and the musician will understand that you have issued an eviction warning. Lucy, blissfully, has never said a word, but I worry all the time that she might, and so I am careful. When her TV characters drift over the wall, I let them in without a word.

Some weeks ago, I was in my room when I overheard an electric guitarist whom I think lives on the floor above. For many months now, I have heard this person work through the same few passages, practiced mostly as one should. Slowly, diligently, until they ring. Starting and restarting, more slowly this time, now much too fast, now the bitterly slow tempo of someone who knows better. A brief silence, for thinking, then restarting. I have memorized every note that this guitarist plays, and in the spirit of romance, I think about playing the passages back as a kind of echolocation. I place my hand against the wall, as though I am quieting an animal. The sound squeezes into my room, lands on its feet, sniffs around. I stick a finger in its mouth and feel the sharpness.

back to home ︎

Kevin Moore

Like Weather

Console yourself, you would not be looking for me unless you had already found me.

--Blaise Pascal

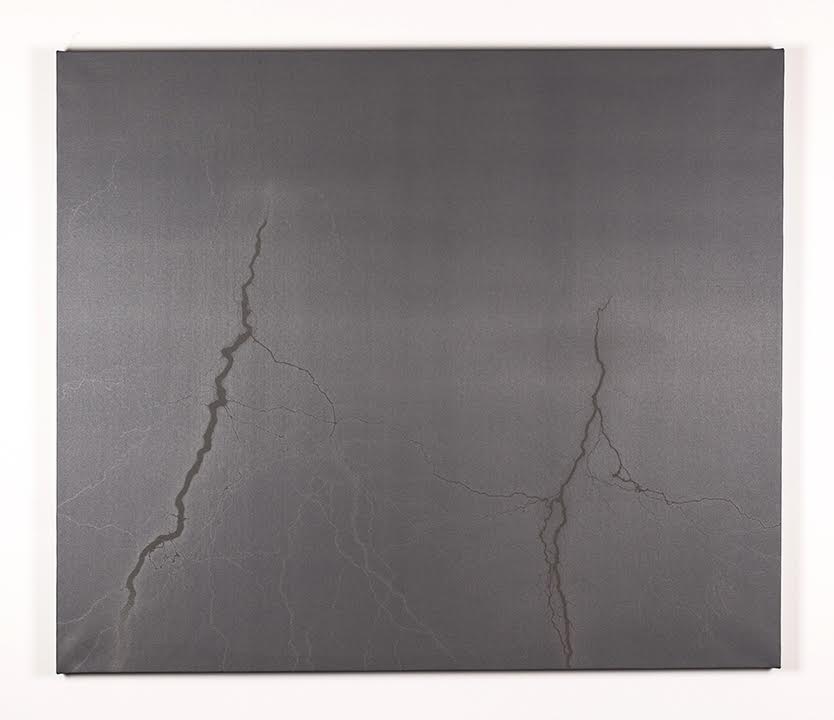

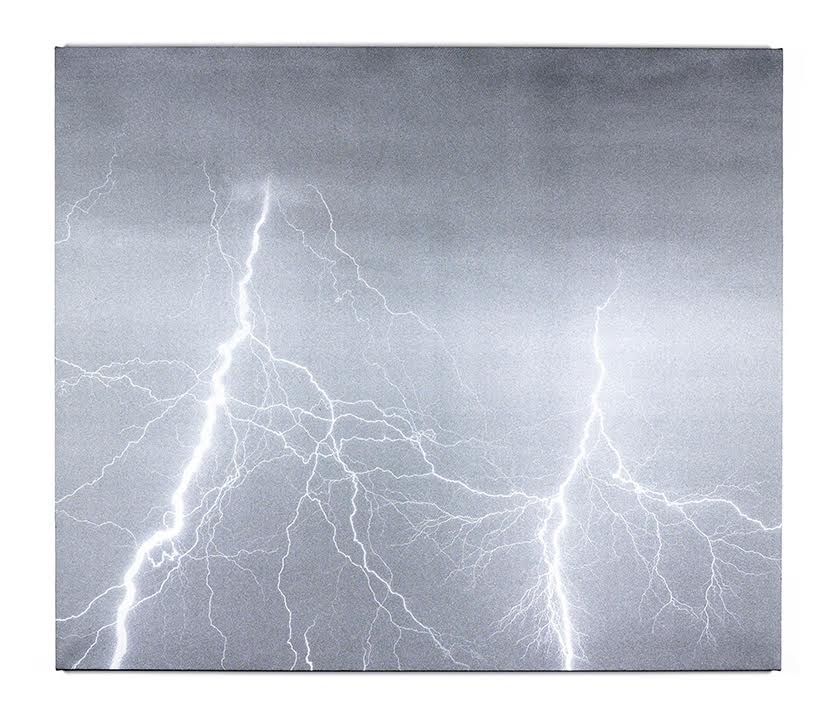

Imagine an art that is more like nature, art you walk through, feel in your nostrils, get doused by. But imagine this art—as so many temporal moments and sensations—objectified, contained, whole. Such is the affect of Robert Buck’s iPaintings, works that exist, as the name suggests, as paintings, yet behave more like mirages: as surfaces approaching and receding, darkening and lightening, containing images—of lightning, eclipses, and smoke—images of ephemeral natural phenomena, by turns revealed and obscured. The iPaintings are also mirage-like in their ambulation: based on stock photographs from the iStock website, selected, cropped, translated to a screen, screened onto a canvas using acrylic and Alert reflective paint, and hung on the gallery wall, they are further subjected to being photographed by viewers and summarily put back into circulation through posting on the web, Instagram, and other social media channels, to be downloaded, cropped, and any number of actions, including made into iPaintings, ad infinitum, again.

The Internet is not nature but it has, of course, natural laws all its own. Sovereign of these is the law of interest-dissemination: items of interest are liked, reposted, and sometimes “go viral.” Whether the iPaintings can properly be understood as entities within the context of the Internet is the open question, for on the one hand they are “of the web,” taken from the web as they might be put back into it, to be consumed backlit on a computer screen, or momentarily “activated” and captured by the flash of an iPhone camera; one aspect of their realism, on the functional side, is the web and its technologies. Yet let’s not forget that the iPaintings—the actual paintings—are also registers for the laws of physics, performing their optical feats as they do in real time and space, for human eyes within bodily proximity—remembering both the “I” and the “eye” in iPainting. For their other realism, more on the phenomenological side, is strictly subjective and perceptual. Trying to get at the intended iPainting experience, between these two realisms, is, of course, the entire point, because the truth is you don’t really get there, you are toggling around a void. Which posits a greater truth, being Robert Buck’s career-long interest in latency, the unsettling notion that meaning is not only buried but multiple, shifting, unstable, there to be revealed, but just for an instant, only to recede and, if returning, appearing next as altered, something else and incomplete. While the cyber version of the iPaintings would seem to contain their meaning and define their place in the world, the other version, relying on the physical encounter and all the myriad coincidences of light, humidity, and mood of the viewer, comes with greater mystery and uncertainty. It is a bit like contemplating the disparity between the dictionary definition of love (“an intense feeling of deep affection”) and experiencing the actual emotion in any of its myriad, often violent, and nuanced forms.

Just what kind of meaning or experience are we talking about here? Starting with the paint surface itself, Alert is a paint with various applications—in the military, aviation, and Emergency Medical Services—that contains glass beads that “light up” when struck by light. Used ubiquitously for road signs, this reflective, utilitarian material holds undeniable poetic properties, such that one might envision, if somewhat fancifully, a sign painter applying lines from Shakespeare—“light, seeking light, doth light of light beguile”—just as easily as the common STOP or YIELD. As for the subjects depicted, barring sunsets and flowers, lightning, eclipses and smoke are about as corny as it gets, not because these subjects are inherently kitsch but because so often the sentiments attached to them, striving to stir emotion, read more like visual cues in a B movie mystery: lightning, a fearful revelation; eclipse, a dark secret; smoke, danger or sex on the horizon. Rescuing these symbols from such media conventions and overexposure, restoring their ephemerality, fragility, and intimation of the sublime, requires something like being in the physical presence of nature itself, or the iPaintings, which in turn requires an openness of spirit, if not a mystic’s bent for divining. For the challenge, thus proposed, is to recognize the signs and assign them meaning—to bear the strike of the lightning bolt and to absorb its significance.

The nature of the message, to the modest degree we are able to make it out, is tantalizingly cryptic, like weather-drawn patterns on glass. Where there is seemingly a figure, there is a non-figure, where there might be a body, an occultation. Circularities of presences and absences, the melancholy of messages glimpsed yet gone, not completely understood. Here we enter the terrain of the vanitas, calling attention to the “emptiness” of earthly objects and experience, all the while fixating on them as glimpsed yet vanished, once held yet lost. The jpeg renditions of the iPaintings behave like the tawny skulls and cracked books and half-burnt candles of those seventeenth-century paintings, reminders of the vanity of our increasing belief in technology, the Cloud, as a means to permanence. Such symbols are but the hollow shells, the mementos mori (“remember that you have to die”) of the act of living and the constant searching that living entails. Yet the paintings themselves are, too, only vestiges, serving as mere stand-ins for the fleeting, lived encounter they attempt to trigger: absences conjuring a blissful fantasy of crystalline revelation, accumulated wisdom, and everlasting physicality. Their presence serves as a reminder that the essential meaning of our existence is of the body and the moment, nothing more.

doris duhennois

who remembers the old fountain

Researched, directed and edited by doris duhennois & filmed and assisted by Mara Chavez

This fountain was inaugurated on the 12th of July 1856 in the French colony of Martinique which still legally belongs to France today.

The fountain celebrated the arrival of fresh and clean water to Fort-de-France

a much-needed necessity

a real progress

but who built the fountain is another obscure(d) story in the aftermath of the abolition of slavery.

a story involving forced labour and racial supremacy and punitive laws,

limitation of movement and imposition of heavy taxation.

and those who can’t pay must work

and their work must be used to make

generations after generations after generations of Martiniquais

remember the great progress undertaken

under the rule of white settlers.

but who remembers?

the walls

the stones

bear memory

the overgrown trees

the iguanas

the ghosts

bear memory

and work slowly

consistently

unfathomably their way

towards forgetting the name of the man

who thought that place was his.

George Baker

Rabbit Holes (Grammatology)

I enjoy “social media” most when I am writing—not sharing something personal, exactly, but something usually dear to me, even if ultimately “useless.” Not an essay, maybe part of a project, hardly systematic, these “posts” are beholden to no art historical standards of scholarship or research. Most often, I call these short reflections rabbit holes; they give me an outlet for all the interests that arise and then fade away, that spark something that may come to fruition later, as something else, but right now needs to be followed to its limits. Digging down deep. For a text that lives for a few people and for a few moments. It is as close as my writing self gets to my teaching self. Thinking out loud. Always digging.

Gordon Parks, Woman who says she is 104 years old, 1943.

This is a photo I came to through the FSA photography resource that is “Photogrammar,” a Yale website. The archive shows that Parks was in Daytona Beach in the early winter months of 1943, mostly taking photographs, hundreds of photographs, of Bethune Cookman College. He took this photo on a clear day in February. A moment later or just before, he would photograph a 3-year-old boy of piercing but worried gaze, his brow knit at whatever he is facing—not the photographer, he looks beyond, on the same oblique as the old woman—looking at history perhaps, or toward history rather. It was the Second World War, it was and is America and he is just three years old in his tight wool cap and his oversized coat with its military patch, just three years old and African American. His face is a weather vane. Other photographs, on the same porch, always with the wood post for comparison: A young woman resting her face in her hand, looking stage left as everyone did that day; an old man, in two coats and a sweater and a bowler hat, his ears akimbo, reminding me in almost all ways of the forensic look of Richard Avedon’s portrait “William Casby, Born a Slave,” 1963, that Roland Barthes included in his book Camera Lucida (“the essence of slavery is here laid bare: the mask is the meaning, insofar as it is absolutely pure…”). The old woman and the old man would sit together on the porch, another portrait, her always in her shades against the Florida light, a 7-Up sign behind them in the shadows. Her sunglasses seem to reflect Parks himself. It is the photographer’s version of the Arnolfini Wedding Portrait. And while I don’t think the single portrait of the old woman is one of Parks’ well-known photographs—I came across it by accident—it seems to want to be emblematic, like his images of Ella Watson in Washington, D.C., as his FSA work began.

The old woman would have been, like Casby in Avedon’s portrait, a living connection to the 19th century, to the Civil War; she would have been born under slavery. But she is all lifted up by Parks’ camera, her head tilted upward, the sun no bother. The store and its 7-Up sign cooperate, like the RC Cola sign in the photo of her male companion—Royal Crown, underlining a reading of his beautiful if well-worn bowler hat—and the wooden post makes of her a heroic monument. She is shadow and she is light, framed by her jacket’s dark fur trim and the black of the contact sheet, encircled by a sunhat of one hundred individual halos, casting lines of sunlight on her face, echoing and displacing her wrinkled skin. In her sunglasses again you see Parks, maybe, perhaps. He seems really well-dressed, in his Sunday finest, in a suit jacket at least, the future director of Shaft. You see the world reflected, in the reflection of this photograph of an African American of extraordinary age. And you do the math, seeing that her claim to be 104 in 1943 means she would have been born in 1839, the year of the public announcement of the invention of photography. Like Ella Watson, the woman is Parks’ personification of the genius of photography. She is a photograph—She is photography—like Watson was, photography as Parks imagined it.

Alan Trachtenberg (1932-2020) by Walker Evans, September 15, 1974.

Trachtenberg had a full-blown theory of photography, a response of sorts to Susan Sontag, and he has not been widely enough recognized for this. It involves a theory of photographic relations, a theory of spectatorship, of how a viewer relates to photographic images.

Writing in 1978:

“Photography is a specular activity; its images are speculations in the double sense of visions and propositions, appearances and thoughts. The photograph is an imaged and imagined relation to a real object, and re-places the viewer toward the object now caught up in a net of new relations—the intricate web of imagination. The image imagines its viewer-subject into being, gives him or her a place, a set of borders. The act of the camera is perforce fictive, perforce ideological. The viewer’s work is to grasp the imagined relation to the world as an idea, and to play over it the critical light of his or her own desires, and not to flinch from withdrawing, from denying power to images whose ideas debase and deform. Criticism is the health of photography…From photographers who are also critics (skeptics) in this sense, their own readers and perhaps writers, can spring a truly speculative photography.”

“...stressing the ineluctable flatness of the surface...”

—Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting.”

I go down the rabbit hole of the ineluctable, which means something like the inevitable, which has roots in wrestling, in the Latin “locator” or “luctari,” to wrestle. In-eluctabilis, unable to struggle clear of, to escape or to avoid. The word “lucha” or the figure of the “luchador” remembers the roots more clearly, and so I am thinking of Greenberg and Mexican wrestling, towards a Newer Laocoon, another arena in which to act, all of that. Someone must have written the essay already on Greenberg and luchadores? If you dig for a second, you will find all the essays on Greenberg and Sullivanian Therapy, the pugnacious, polyamorous, and fight-prone “Upper West Side Cult” to which he adhered. Ineluctable. Fate as a headlock.

Adventures in summer reading. Yes, I'm reading Hemingway again, and sit by the pool to finish A Moveable Feast. But I am distracted by the young woman that comes out to sunbathe. No, not that way, she is on her phone of course the whole time, and the entire conversation puts Hemingway to shame. There is talk of her upcoming marine safari to watch the sardine migration off the coast of South Africa, to see the sharks feeding on them; there is talk of her friend on a safari watching the wildebeest migration across the plains; she tells a tale of being hit by a whale fin slapping the ocean water; she asks her friend if she has ever run with the bulls in Pamplona, and says she is going with her military friends, the only woman in the group, to run with them next year.

I finish the Feast, and move on to a novel by Elsa Morante, and the narrator tells a tale of seeing a white “dugong” crawl out of the Mediterranean sea onto his island. I have never heard of dugongs and look them up, losing an hour. But then I remember that I began my day over morning coffee reading of Doggerland, a lost area of Europe hit by a tsunami 8000 years ago, a real “Atlantis.” I ponder the connections, the dugongs and Doggerland, in the style of my friend Joni Spigler (you should know her). I read a specific account of the dugongs, searching for them off the Philippines, and the guide's name in the story searching for the dugong is Dogong. I read:

“Dugongs (Dugong dugon) are distant cousins of elephants—they grow up to three-meters and weigh about 400 kilograms. Also called sea cows, they inhabit shallow waters of the Coral Triangle, wherever seagrass is abundant—hence the bovine reference! They are the fourth member of the order Sirenia, alongside the three manatee species. The Steller’s sea cow was a truly gigantic cousin at 8 meters in length—but the last of them was in 1768. Dugong comes from the Malay word duyung, which means ‘lady of the sea.’”

Who were you? is a rabbit hole I often go down. I spend the day beating the heat with an execrable book, skimming, the book on the Black Dahlia murder and Surrealism. Struck by the wedding photo at the double wedding of Man Ray-Juliet Browner-Max Ernst-Dorothea Tanning hosted by the Arensbergs in Hollywood, taken—the book tells me—by a “protege” of Man Ray named Florence Homolka. I go down the hole, finding the blazing portraits of her taken earlier in the 1930s by Man Ray. Obviously in Paris, not the local LA story I am expecting. And then I quickly realize she was Florence Meyer, before she married the actor Oscar Homolka—Katharine Graham’s older sister, daughter of Agnes Meyer, member of Stieglitz’s circle, friend of Picabia. Her childhood “home” in Westchester was where the massive “lost” Picabia abstractions now at MoMA were found in the 1970s, rolled up in the basement under birdcages and a croquet set. The estate owned now, maybe only for a little while longer, by Donald Trump.

I find a photo of her, appropriately, by Steichen. She wanted to be a dancer. I become intrigued by the many photos I begin to find of her, very young, taken by Brancusi—clearly in his studio. And then later, photos by Homolka, of Brancusi, or of his studio, of his sculptures treated like Man Ray & Co.’s heads in the double wedding portrait. I find notices of an Eastern European auction, held during COVID year 2020, selling off a trove of Brancusi’s love letters to Homolka. They seem to stretch over twenty years. He writes in French, signs his name in code, but always calls her “Darling,” in English. She died suddenly, in 1962, in her home in Bel Air.

Who were you, Florence Meyer Homolka.

Morning rabbit hole. Picabia grew up an only child, as a child, but later he did have a much younger half-sister, who was friends with Duchamp’s sister Suzanne, and shared Duchamp’s other sister’s name: Yvonne. Picabia made a drawing of her when she was about 18 or 19 years old, it was in his “anti-Dada” figurative art show chez Danthon, in 1923, and it was until recently in a private collection in Encino. I don’t know too much about Yvonne yet. She wrote—she made books—she shows up on the Google as a “judge” in a naturist beauty pageant in the 30s in France. I recently added this later book of hers to my library: Histoires de marins et chansons rochelaises. It is filled with stories, songs, and drawings that seem to share a lot of the (Francis) Picabia topoi—dogs, drunken dogs, a monkey, graffiti, kitsch portraits … Who were you Yvonne (Gresse) Picabia?

Rabbit hole du jour. Here is a Man Ray group portrait from around 1930. It often gets wheeled out now to speak to the Surrealist group’s complex position in relation to homosexuality. In her otherwise incredible anthology on women surrealists, Penelope Rosemont points to the photograph as her reason for including the artist Georges Malkine—here in the back, on the left—as one of the queer surrealists, along with René Crevel and Louis Aragon (and Claude Cahun, and Valentine Penrose, and ...). But the photograph proves more complicated than that, more wild, and more in need of history. Robert Desnos is at the center, beautiful Desnos, who eventually died in the concentration camps, of typhoid, just before the camps were liberated (this fact often now gets wheeled out to speak to the Jewish members of the Surrealist circle, but Desnos was not in a concentration camp for being of Jewish descent—more history needed here as well, another rabbit hole to plumb). In the wake of Man Ray's film Starfish, made with Desnos, to one side is the actor from that film, André de la Riviere. To the other side of Desnos is André Lasserre, a Swiss sculptor, animalist and student of Bourdelle, why is he there? I love him for his biography, and his work on a monument to Paul Lafargue, Marx's son-in-law and author of The Right to Laziness. The most underknown of artists from the original Surrealist group is then behind, Georges Malkine, but he is kissing his wife, Yvette Malkine, who wore her hair short and “dressed in masculine guise” in these years.

And so the group portrait of a kind of collective embrace (the grasping hands, the interlocked arms, the gazes) does open onto a queer history, to be plumbed. Yvette Malkine was born Yvette Ledoux, in 1898 in Canada; her father was Urbain Ledoux, a figure more remembered now than his daughter perhaps, an American diplomat who became a peace activist, an early American convert to the Baháʼí faith, a “champion of the outcasts” who also called himself “Mr. Zero.” As in, when asked who he was as he ran bread lines and other resources for the destitute in New York, the impoverished of The Bowery,

“I am nothing, call me Zero.”

Yvette Ledoux shows up as the character “Angela Martin” in John Glassco's memoirs of Montparnasse. She had been a nurse in Europe during WWI, a dancer in the Ziegfield Follies, a part of an artist colony in Woodstock, NY. In 1920s Paris, she was the lover of the British lesbian sculptor “Gwen” Le Gallienne, notable for her nonconformity “even in Montparnasse.” The anti-Hemingway memoirs of the sexually-fluid fellow-Canadian Glassco remember Yvette and Gwen Le Gallienne and a dinner at “Chez Rosalie,” on the rue Compagne Premiere, which is also where Man Ray had his photography studio. In a blog about the food habits of bohemian Paris, I learn that Glassco memorializes the night at Chez Rosalie, as “run by one of Modigliani’s former models and well-known for the being ‘very good and incredibly cheap.’ Glassco is turned on by the amount of food the two girls eat. ‘They worked their way enthusiastically though the entire menu of the prix fixe and I found their healthy girlish appetites stimulated my own. We finished off with a chocolate mousse served in little earthenware pots covered by a circle of silver paper.’ Glassco follows the girls home to enjoy a night of three-way pleasure. The next morning the two girls start eating as soon as they wake. Buttered tartines, anchovy paste, tea and apricot jam: a feast of French and Anglo delights far more gluttonous than the pared-down breakfast Parisian women supposedly allow themselves today. Glassco leaves the apartment and buys himself a French pastry full of yellow custard. He is definitely with the girls on this occasion.” By 1929, the two women would sail for Tahiti, with Georges Malkine, and Yvette and Malkine fell in love on this voyage.

Unbelievably, the boat they sailed on was named “Antinous.” (The famed young lover of the Emperor Hadrian.)

This is the background I know so far to the group portrait by Man Ray. It is not an image of Malkine the gay surrealist, not exactly, but it is also a portrait of another Malkine the gay surrealist. There must be better ways to frame this, the homophobia of surrealism or the queerness of individual surrealists not the issue—rather the fluidity of these categories themselves. The photograph fixes nothing. And then, and then, I lose track of Yvette Ledoux Malkine. Where did she go after the portrait? What did she do? All I know for sure so far is that by the outbreak of WWII, she would leave Malkine to return to New York, to care for her father. Mr. Zero died in 1941. Yvette did not succeed in her efforts to get Malkine to leave Europe too, to join her in New York. Still alone, she died just at the war’s end, of tuberculosis, in November 1945, in the VA hospital that specialized in treating TB, just north of Beacon, in Castle Point, New York.

I will never visit Dia:Beacon again, without thinking of this photograph by Man Ray, of Yvette mistaken for a man, of the nonconformity of hers and many lives, and her demise so close by where I grew up—and never knew of her.

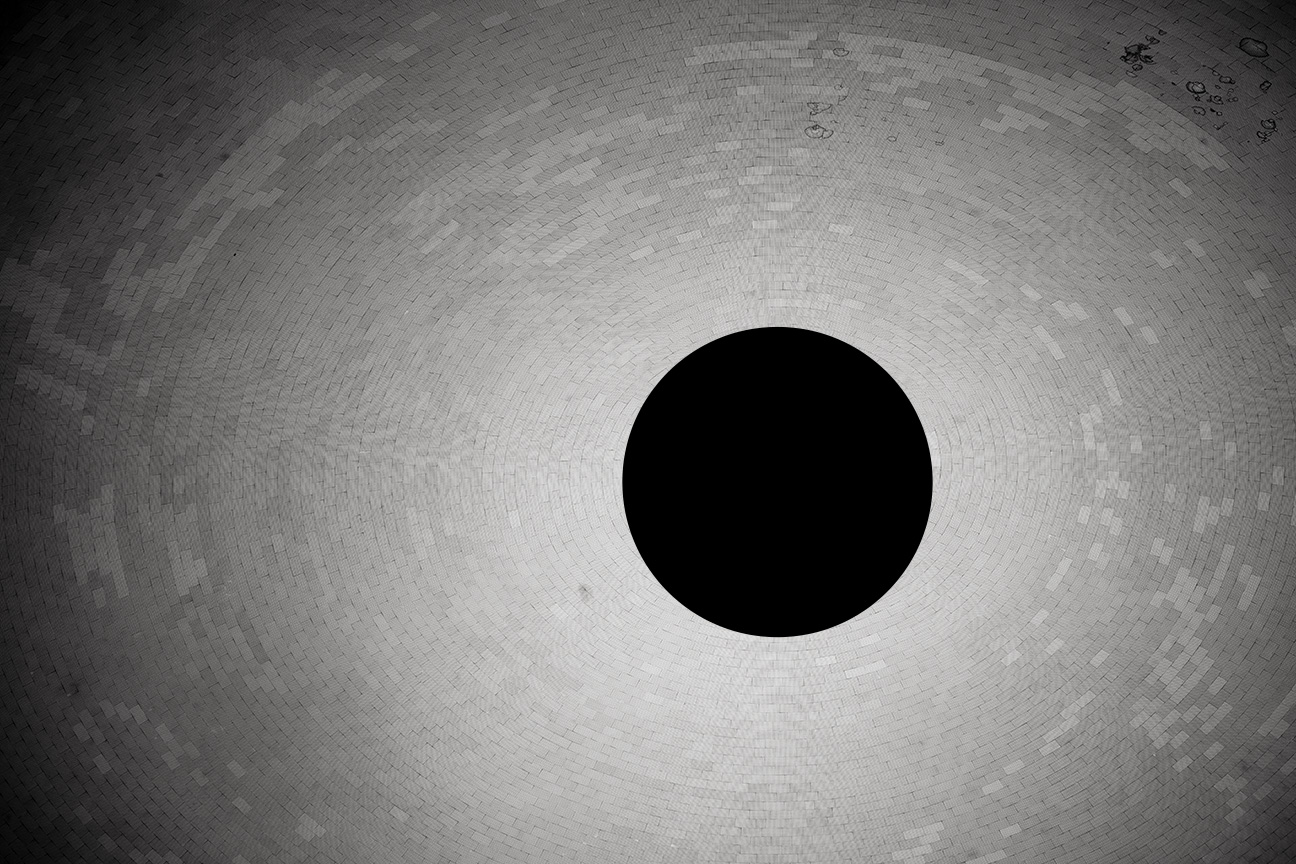

“The living being had no need of eyes because there was nothing outside of him to be seen; nor of ears because there was nothing to be heard; and there was no surrounding atmosphere to be breathed; nor would there have been any use of organs by the help of which he might receive his food or get rid of what he had already digested, since there was nothing which went from him or came into him: for there was nothing beside him. Of design he was created thus; his own waste providing his own food, and all that he did or suffered taking place in and by himself. For the Creator conceived that a being which was self-sufficient would be far more excellent than one which lacked anything; and, as he had no need to take anything or defend himself against any one, the Creator did not think it necessary to bestow upon him hands: nor had he any need of feet, nor of the whole apparatus of walking; but the movement suited to his spherical form which was designed by him, being of all the seven that which is most appropriate to mind and intelligence; and he was made to move in the same manner and on the same spot, within his own limits revolving in a circle. All the other six motions were taken away from him, and he was made not to partake of their deviations. And as this circular movement required no feet, the universe was created without legs and without feet.” ---Plato, Timaeus

All of the short texts here were written on my iPhone, to be posted on Instagram. They are in no specific order, are no longer chronological, and have been edited slightly and lightly for this context. --GB

Iury Salustiano Trojaborg

A Backyard of Affections

2023Image projected on bathroom curtain while audience enters:

Natureza em Tibirke, Tibirke, Denmark, 2013. © Iury Salustiano Trojaborg

Once audience is seated:

Iury is dressing herself behind curtains. Audience sees her silhouette only.

One navy blue military jacket, military boots, and a blue and green bathing suit are hanging in the space.

Voice off:

In 2018 I was 38 years old and I had been living in Berlin for over 5 years. At that point of my life, I had been in a depressive state for one year. I decided then it was finally time to create a performance where I would tackle the difficult relationship I had with my father my entire life. The first thing I decided was that the performance should be called Stories of a Feud (it appears projected on shower curtain) which would contain short stories, written in the first person, mainly dealing with my rigid upbringing as the daughter of a Navy commander and helicopter pilot in Sao Pedro D’ Aldeia, a small town located two hours away from the state capital, Rio de Janeiro. I spent ten significant years of my childhood there and my father still owns the house where my brother and I grew up. Once I started writing the Sao Pedro stories though, I remembered other meaningful stories that had taken place in other cities, such as Salvador, capital of state the Bahia, where I spent the first year of my life. Then even more stories came to the surface such as those taking place in Aracaju, capital of the state of Sergipe where my father served for two years as the highest maritime authority.

Because these were autobiographical stories told from my point of view, I decided that for the performance, they should be accompanied on the stage by photographs and real memorabilia pertaining to my family. Most of these objects, pieces of clothing, photographs, handwritten letters, drawings, cassette tapes, etc., are now with my father in the old family house, so I sent him a message to check the possibility of getting access to this material. Here’s the answer I received from him:

Performer plays WhatsApp audio message sent by Sonilon on October 23rd 2018 04:11am:

Iury, o que eu quero dizer é o seguinte, boa noite, eu tenho muita coisa para fazer, cara, é… a sua prioridade não é a minha prioridade, não que eu não queira te ajudar, agora você me faz uma porção de pergunta, quer uma porção de coisa antiga, eu tenho que revirar muita coisa, eu não sei qual é a sua ideia, eu não entendo perfeitamente essa ideia de performance, são umas coisas que não são do meu mundo, bicho, o meu mundo é diferente, o meu mundo é feijão com arroz e pé no chão e cartesiano, então eu posso lhe ajudar, mas não me cobra prazo porque eu não tenho prazo, eu trabalho muito bicho, eu passo mais da metade do mês dentro de um hotel voando o dia inteiro sem tempo para nada, eu tenho pouco tempo em casa então dentro das minhas possibilidades eu vou te ajudar, vou tentar ver isso aí, mas voce cismou com um negócio, uma loucura (…)

Iury interrupts when the word “loucura” comes up. The word “loucura” is projected on the shower curtain.

(…) I haven’t understood a thing of what it is you want to make, whose story do you want to tell? Why don’t you tell your story instead of mine? Your story is your story, my story is my story; but then you start to mix in my marine corps graduation voyage, my marine corps uniform, plus the photography of your grandmother. Listen, honestly, this is madness (…)

Iury interrupts the message when the word “madness” comes up. The word “madness” is projected on the shower curtain.

(…) I will help you in my own time, as much as possible; I cannot just stop my life, a life already very complicated, just because of a whim of yours (…)

Iury interrupts again when the word “whim” comes up. The word “whim is projected on the shower curtain.

(…) because of this need of yours; so in time I can help you, maybe not at your speed but rather at my speed, my availability. I understood what it is that you want, so I am going to look for it, copy. I just don’t understand what my marine corps graduation voyage has to do with your life, what my marine corps uniform has to do with your life (…)

Performer interrupts the message when the sentence “I just don’t understand what my marine corps graduation voyage has to do with your life, what my marine corps uniform has to do with your life” comes up. The sentence is projected on the shower curtain. Finally, she plays the message to the end.

(…) this is just madness, what you have in your head; I really cannot understand you and you cannot explain it to me, right? So, within my availability, and at my own speed I am going to check what I can do to help you, ok? A goodnight kiss.

Iury performs the answer sent via WhatsApp on October 23rd 2018 11:24am:

Dad, I can explain to you in details the genesis of the performance I intend to create. When you have some free time, call me and I will be more than happy to share my ideas with you. What I am working on right now is not “madness”, as you defined it. It’s just an attempt to understand myself through my ancestors. Not everything that one doesn’t understand can be named “madness”. Following your logic, I could also call your life and your work “madness”. But I don’t, out of the respect I have for you and also for believing that people are different, there are so many different ways of leading one’s life and how to exist in this world. And I profoundly respect differences. I thank you in advance for your support and I put myself at your disposition for a conversation about my ideas.

Iury dresses military with every story and has a comment on each accessory that they are not the original ones, but replacements.

Story 1: Salvador, Bahia

I was born in July 1979 during the Brazilian military dictatorship in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Though my parents were not living in Rio at the time of my birth, but in Salvador, capital of the state of Bahia, a city located 1600 kilometers away from Rio. They were living there at that time because my father joined the Marine corps at a young age, which meant he was often transferred from one city to another, as he moved up through the ranks over the course of his nearly life-long navy career. That also meant that my father would spend a great deal of time joining military expeditions far away from home and his family. Sometimes for several months at a time.

My parents used to tell me this story: Right before my birth, my mother decided to travel to Rio so that I would be born in the same city where both my parents had been born, adding, in this way, the proud citizenship yet another carioca to the family. That’s what Brazilians call people who are born in Rio de Janeiro: carioca, with a sense of central-southern pride. In order to make the story of my birth even more grandiose, they used to tell me that this was my first plane trip, crossing Brazilian skies some 35.000 feet above the ground in my mother’s womb, just to become a carioca. I used to love this story when I was a kid and spread it widely among my friends in school. But many years later, I learned that this was a one-sided version of the story. Another version is that my mother flew to Rio so that she and I would be assisted by my grandmother and my aunts during the first weeks following my birth, rather than my mother being left alone in Salvador, a city she had just moved to where she didn’t know anyone.

This actually happened. My father was traveling when I was born and got to see me only three days after my birth. I had not been made aware of that though.

It took me 38 years to learn that my father was absent when my mother gave birth to me. She only revealed it when I asked her about the real reason for the trip to Rio de Janeiro. Then she showed me this picture of our first encounter:

This photo tells a story I now have trouble believing: the caring father feeding his baby. What I mostly remember from my early years is his absence.

It is confusing to me why after all these years why I still feel my father’s absence.

And why somewhere deep down I am still looking for his approval.

Until when?

For how long am I going to allow myself to walk in these shoes of oppression?

Story 2: Sao Pedro d’Aldeia, Rio de Janeiro

In December 1982, my father was part of the first Brazilian expedition in Antartica, where he spent four long months away from home. I now understand what a great professional achievement it might have been for him. Back then though, for my mother, my brother and I, it was not the happiest of times. It did however provide me with one of my earliest memories: I was 3 years old and I might have been acting a bit strange because my mother kept asking: “What’s going on with you?” I couldn’t reply, I didn’t know. I couldn’t understand my own feelings. That much I remember. After much insistence the only reply I could give was: I miss my father. Yes, despite my strict military upbringing, despite all the chores we had to do every Sunday, such as cleaning the garden, brushing his boots, sweeping the front of the house, washing and polishing both cars etc., despite all those things that I hated so much, those things that kept us from spending Sunday at the beach, I still missed him when he was not around. And he was quite often not around, but involved in military exercises and I remember thinking: what threat are they preparing for? It didn’t seem to me that there was any war to prepare for, and the only threat I remember feeling quite vividly was the possibility of losing my father in a helicopter crash. Every now and then there was a helicopter accident in Sao Pedro D’Aldeia, leaving a military widow and fatherless kids. I still remember one of my classmates, Elson. We were in the 4th grade. One day somebody came to pick him up early from school. Not long afterwards, I heard my mother talking to someone and soon the whole town knew: Elson’s father had been killed in a helicopter crash. That left me sleepless for many nights, thinking my father could be the next.

Story 3: Aracaju, Sergipe

It was supposed to be a boat trip. That’s how my father had announced it. My brother and I got very excited. But an alarm bell rang in my head as soon as I saw the boat, which was actually a cargo ship. To my childish eyes, a huge one. I was 11 years old and we were living in Aracaju, located some 300 kilometres away from Salvador. Already at that age, I understood that we wouldn’t be making a Sunday boat trip on a big ship like that. Something smelled off. There was a lot of wind as I watched the coast slowly disappearing. Everybody seemed to be having a good time while all I thought was: When are are we going back? Then something began to appear on the horizon. A black dot that slowly grew larger and larger. My father and the crew started discussing something but I still couldn’t grasp it. Then, right before my eyes, the small black dot became huge: It was an oil platform. I had never seen one before. Then a new announcement was made: the ship is continuing its journey into the open sea, so we have to move onto the platform in order to return to land. Nobody had told me that before. I became very nervous. I couldn’t accept that betrayal. Imagine a crane hoisting a big block of rock from the ground on a construction site. That’s how we were supposed to be transferred from the cargo ship onto the oil platform and then afterwards onto a much smaller ship, that would finally bring us back to land. To safety, as I thought of it. While being hoisted up from the ship by a crane, All I had to hold on to was a thin piece of fishnet placed in front of me. I heard laughter and screams and I did not dare looking down into the ocean. I felt frozen, paralised and betrayed. I was in shock, I would say. To my father though, I preferred to say nothing in order not to awaken his anger.

Didier Eribon’s Returning to Reims excerpt:

“How the traces of what you were as a child, the manner in which you were socialized, persist even when the conditions in which you live as an adult have changed, even when you have worked so hard to keep that past at distance. And so, when you return to the environment from which you came - which you left behind - you are somehow turning back upon yourself, returning to yourself, rediscovering an early self that has been both preserved and denied. Suddenly, in circumstances like these, there rises to the surface of your consciousness everything from which you imagined you had freed yourself and your personality - specifically the discomfort that results from belonging to two different worlds, worlds so far separated from each other that they seem irreconcilable, and yet which coexist in everything that you are. This is a melancholy related to a ‘split habitus’to invoke Bourdieu’s wonderful, powerful concept. Strangely enough, it is precisely at the moment in which you try to get past this diffuse and hidden kind of malaise, to get over it, or when you try at least to allay it a bit, that it pushes even more strongly to the fore, and that's when the melancholy associated with it redoubles its force. The feelings involved have always been there, a fact that you discover or rediscover at this key moment; they were lurking deep inside, doing their work, working on you. Is it ever possible to overcome this malaise, to assuage this melancholy?”

Eribon, Didier. Returning to Reims. Translated by Michael Lucey. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), p.19

Iury dresses in Voinha’s bathing suit:

Somewhen along the way, I realized how painful and difficult it was to create a performance about the struggles I went through with my father during a depressive crisis. I decided then to turn my attention to my maternal grandmother Voinha, a source of love and inspiration throughout my life. A show initially named Stories of Acceptance (projected) became in the end Feliz Aniversário (Happy Birthday), a celebration of Voinha’s 100th birthday, presented at Hebbel am Ufer Theater in Berlin in November 2020.

In December 2022 I went back to Voinha’s first address in Rio de Janeiro, the same place where we had last met in September 2018. Despite the lack of her bodily presence, I searched for traces of her existence and ways of communicating with her by listening to the environment at my disposition. The recordings of our ancestral exchange were based on the knowledge of the soil, of the flora, of the wind and of one particular memorabilia: Voinha’s ever-present sewing machine.

Voinha was the first person I met who seemed to exhale a sense of freedom and self-control by not allowing anyone to subjugate her. Already from an early age I longed to be free the way Voinha was. Her mixture of a strong-willed and independent personality with an extremely loving and caring presence was an example for me. Voinha was the first non-binary person I met.

Muito obrigade, Voinha. For showing me a way out.

Iury bathes herself in a bathtub.

Video: Quintal de Voinha, by Hilnando, Iury and Lucas Martins

Needless to say my father never responded to my request, so now I am having to make do with replicas of family tokens.

Five years later, I am still trying to tell these stories in order understand my father and, consequently, myself. Maybe I never will. But I keep on trying.

I am my father, but I am also my grandmother Voinha. I am many others who have crossed my different paths along this long journey of migration.

As the genesis of this performance has now taken more than five years, maybe I will need other five to conclude it. Or even fifty and, who knows, five hundred years and a million other stories.

So, Salvador, Sao Pedro d’Aldeia, Rio de Janeiro, Aracaju, Doha, Salzburg, München, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Copenhagen and now Malmö are not only the cities where I’ve lived, but also where I have gathered experiences. Experiences that keep pushing me forward.

Off I go.

Iury and Thiago perform the song Maranhao together.

The End

My current practice as an artist researcher is a consequence of the different educational paths I followed, paths very much informed by a desire of not belonging to rigid epistemological structures and by an attempt to investigate methodologies that contemplate the performative as an arena to deal with the crossing of specific issues related to gender, sexuality, racialization, class and ableism, present in my body and in its relation to the different societies that I have inhabited throughout the last sixteen years since I left Rio de Janeiro for Doha, Qatar and later moved on to the Northern European cities of Munich, Frankfurt am Main, Copenhagen, Berlin, and Malmö.

I understand the performative as a possibility to generate knowledge through the body and via its interaction with other agents, or as scholar Mark Fleishmann in his article The Difference of Performance as Research states: “…performance constitutes ‘an alterity’ that resists the hegemony of the text in the academy. It is a transgression that seeks to break down the separation of subject and object, of body and mind, and therefore it must be either expunged, silenced or policed by the academy (…) What is required is an honest acceptance that the principle of ‘compossibility’ – fleshes alongside images, sight alongside hearing and touching and feeling and moving – is called for”. By making use of autoethnography as both a dramaturgical methodology and a performative tool, I am searching for ways to dramatize and, in this way, re-tell my own and some of my ancestors’ journeys (currently my maternal grandmother and my father’s). I deposit my belief in the iterative power of performance as means to emancipate and to regenerate those involved in such processes.

Iury Salustiano Trojaborg is an interdisciplinary, queer, non-binary, migrant artist who has worked practically and theoretically in Theatre, Performance, Dance and Opera.

Mathilde Bonnefoy

Basim Magdy

Final Release

She was baptized an ambassador

Back when the embassy was in hell

She knew the colors of the rainbow

Were a reflection of her face

Her tears smelled like the Mediterranean

And her cheeks lived up

To her roommates' expectations

The farm was left to rot

The dry canal revealed an ancient

Bitter iron mine

Raging beneath the convoluted

Layers of its masquerading existentialism

Anger can move mountains, they say

But she just laughed

At the blood taste in her mouth

On my 21st birthday I found myself

Sleeping on a stranger’s couch

In Lewiston, ME

All I remember:

A mountain of tie die shirts

Bright green delusion

And the final release

Of religious guilt

I was excited about something

I was never going to find

And there she was

Waiting

For a chance

To

Finally be herself

In the dark wilderness of

Generational pretentiousness

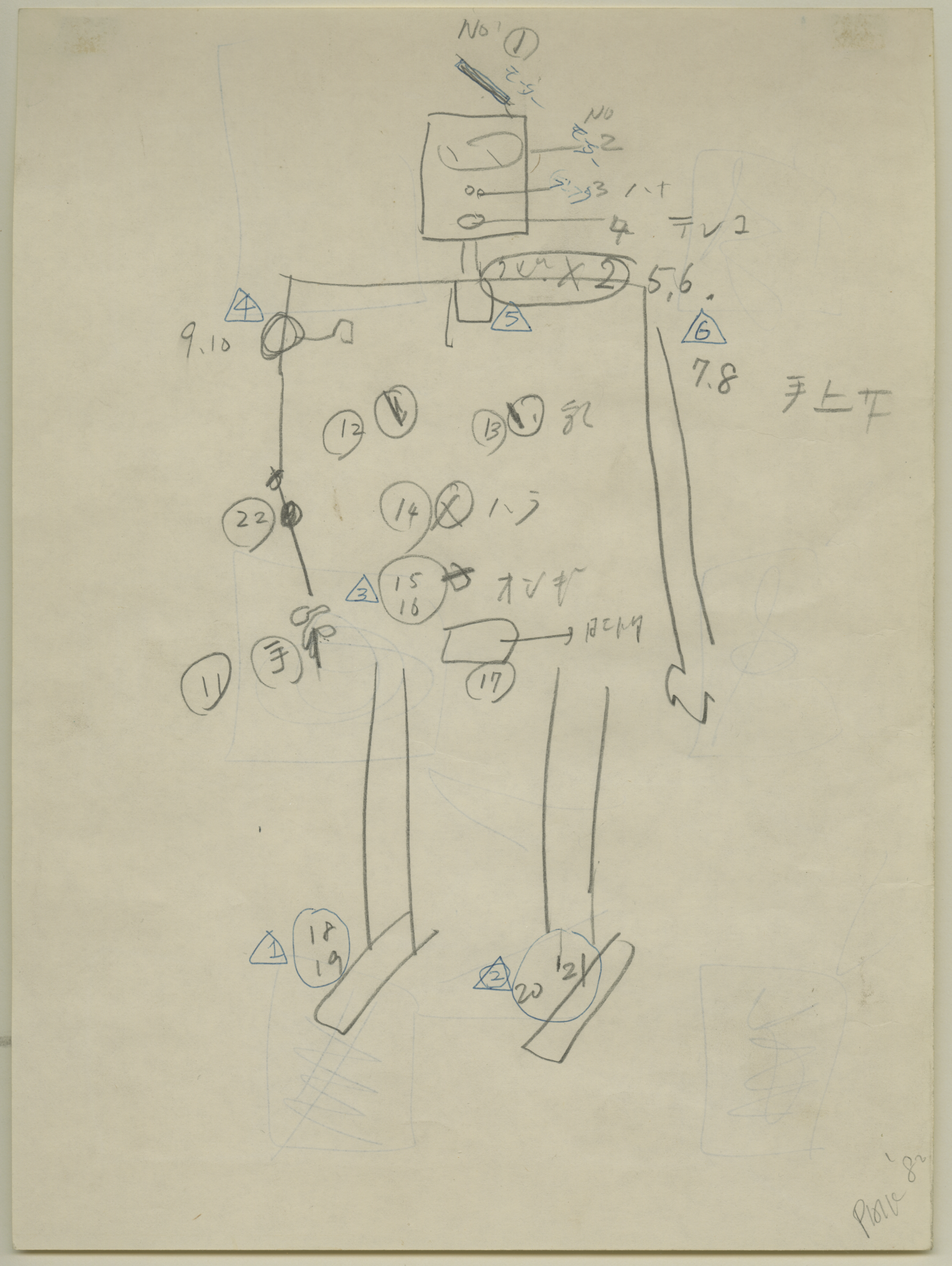

Rachel Churner/

Carolee Schneemann

Carolee Schneemann

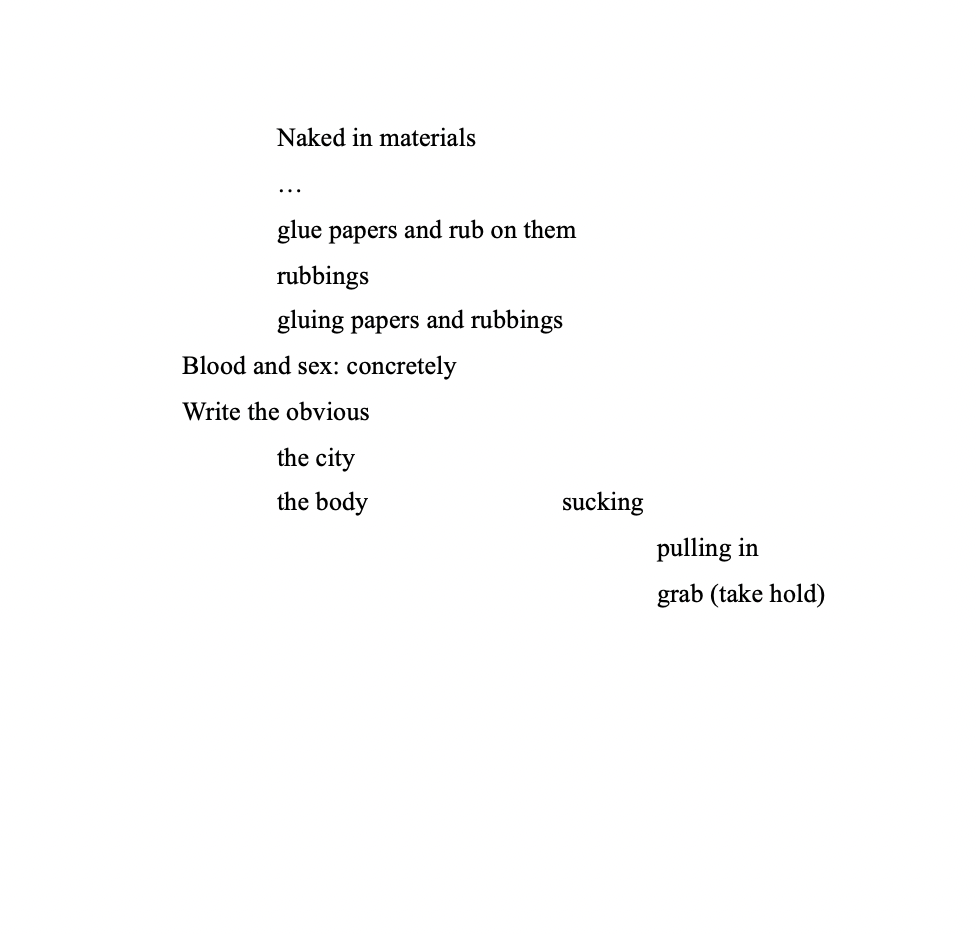

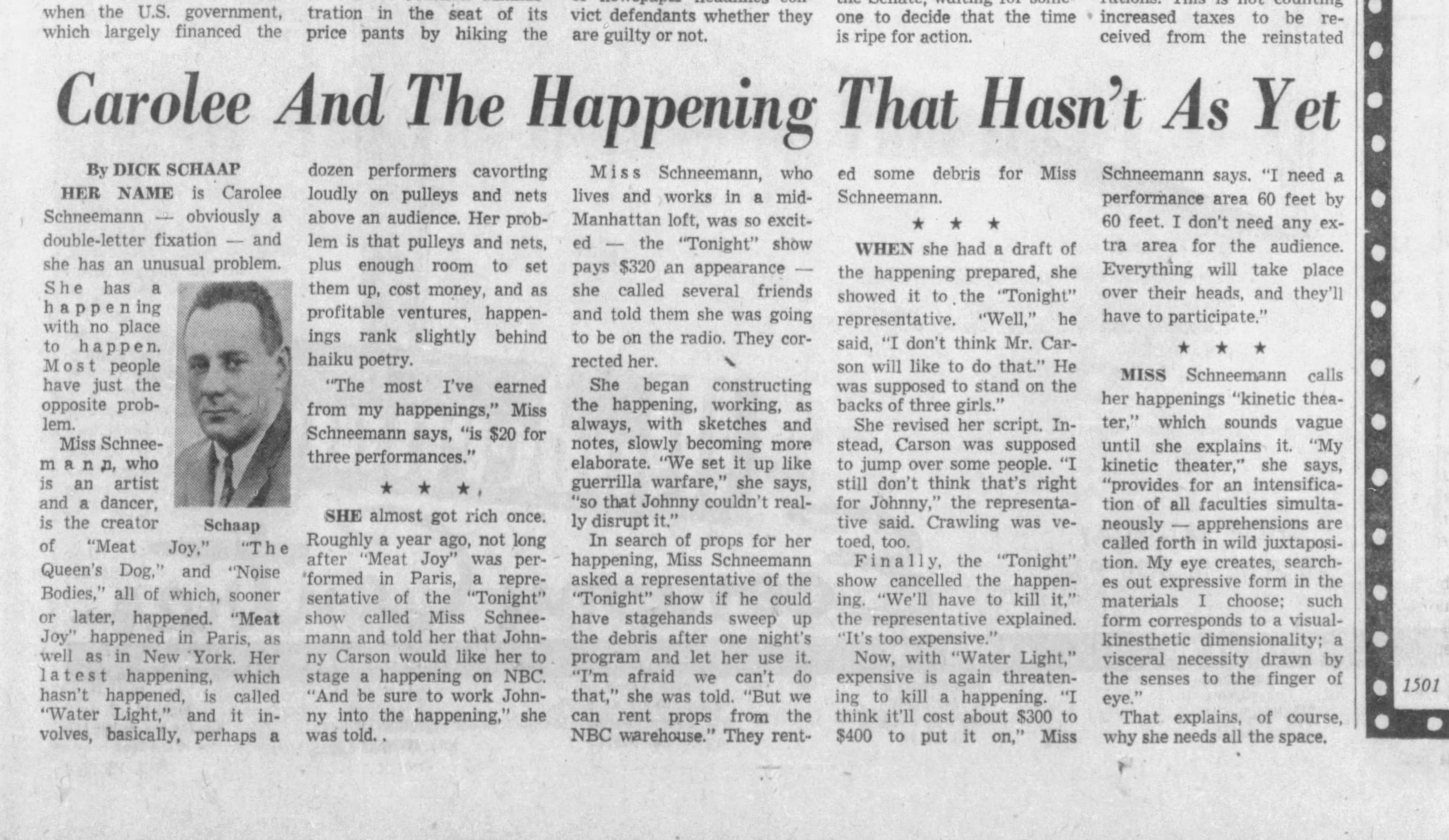

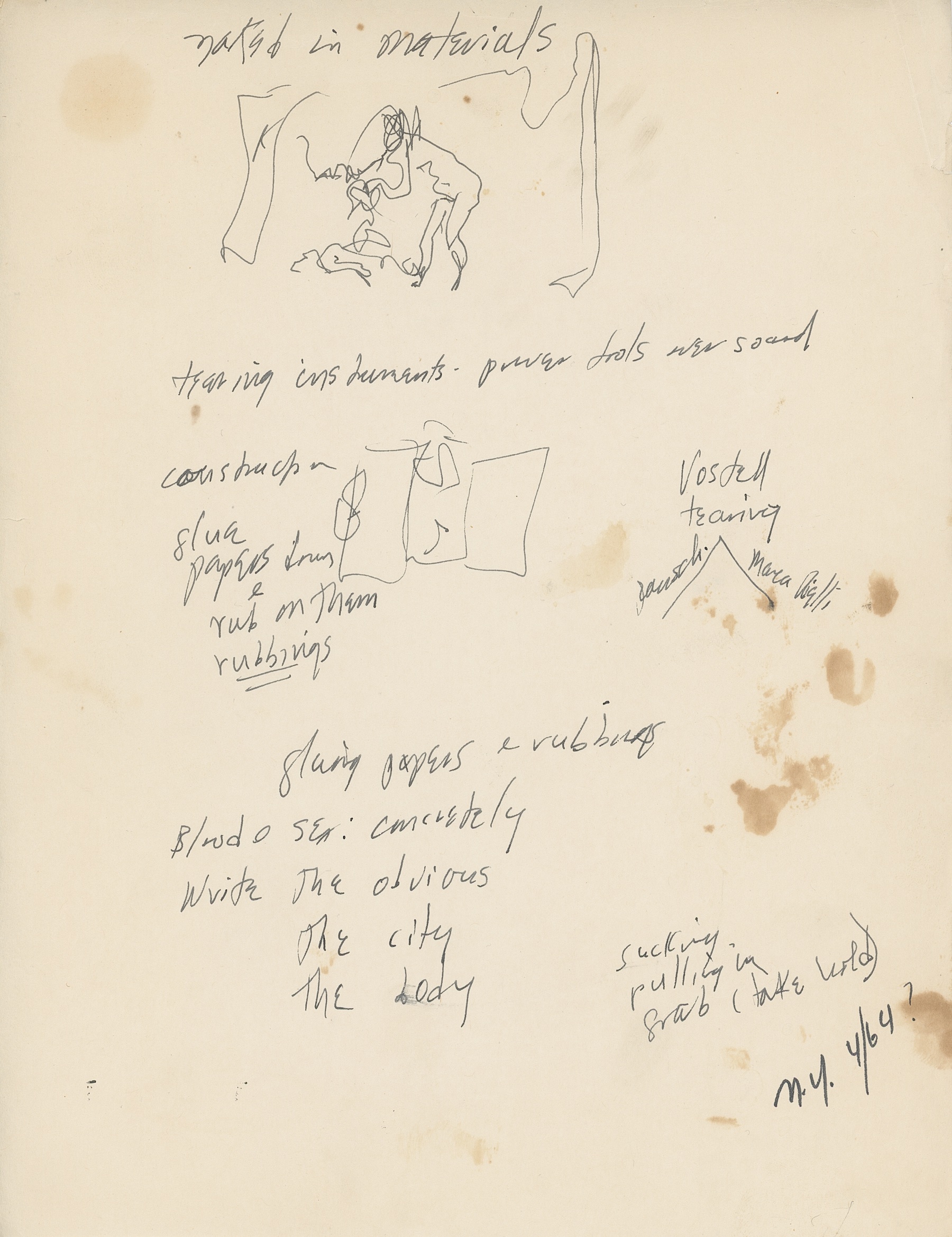

T.V., a Happening

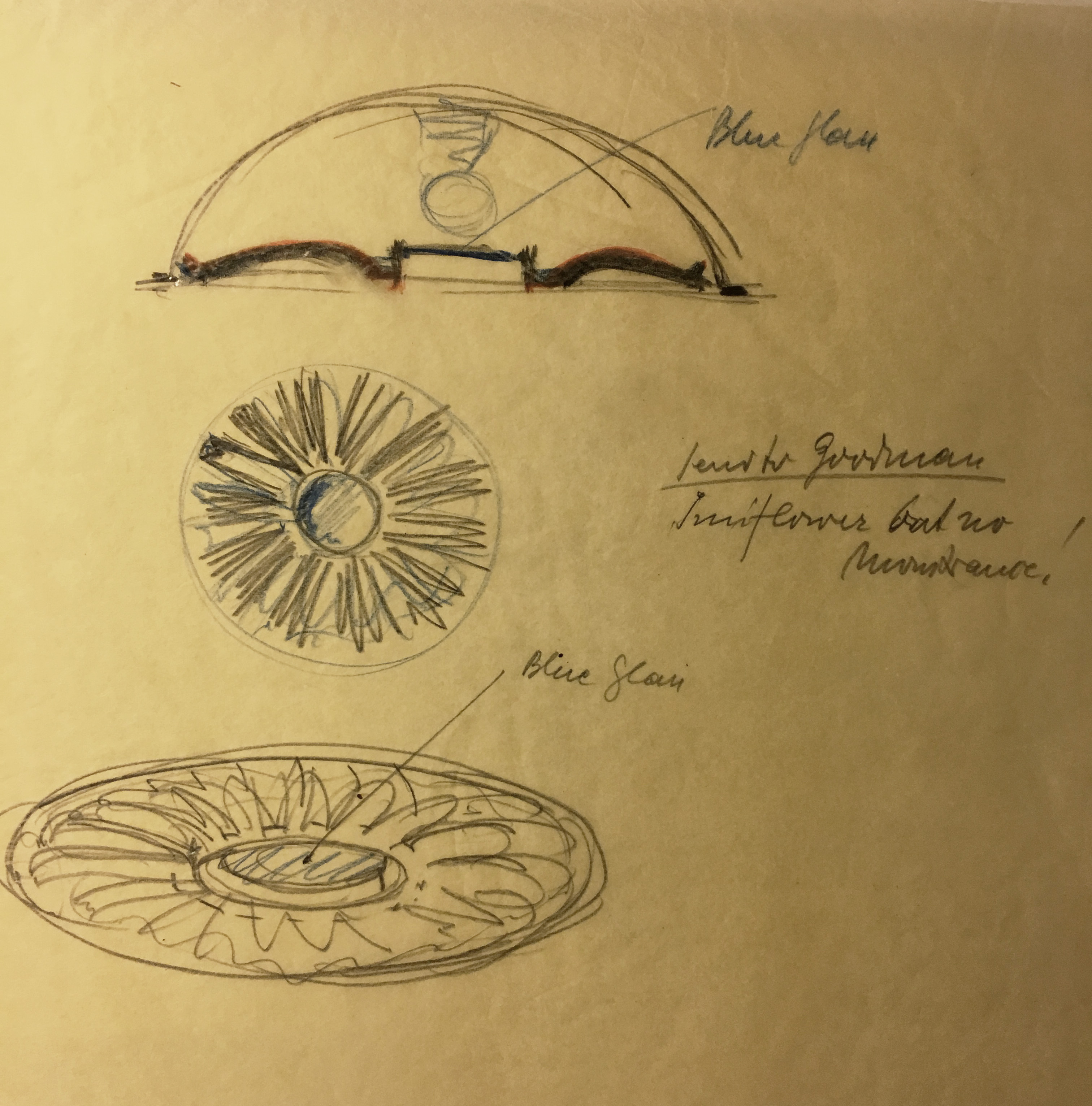

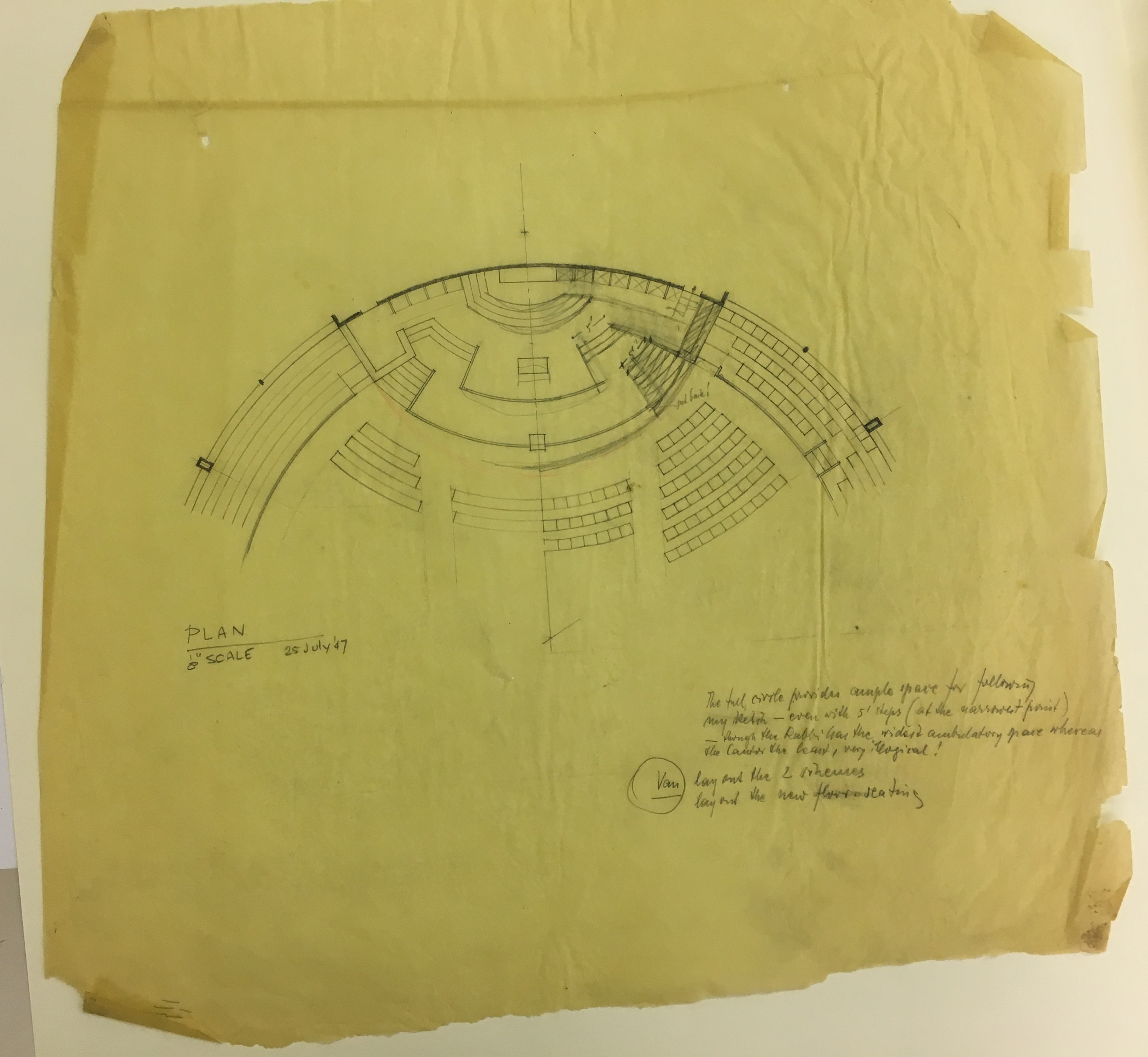

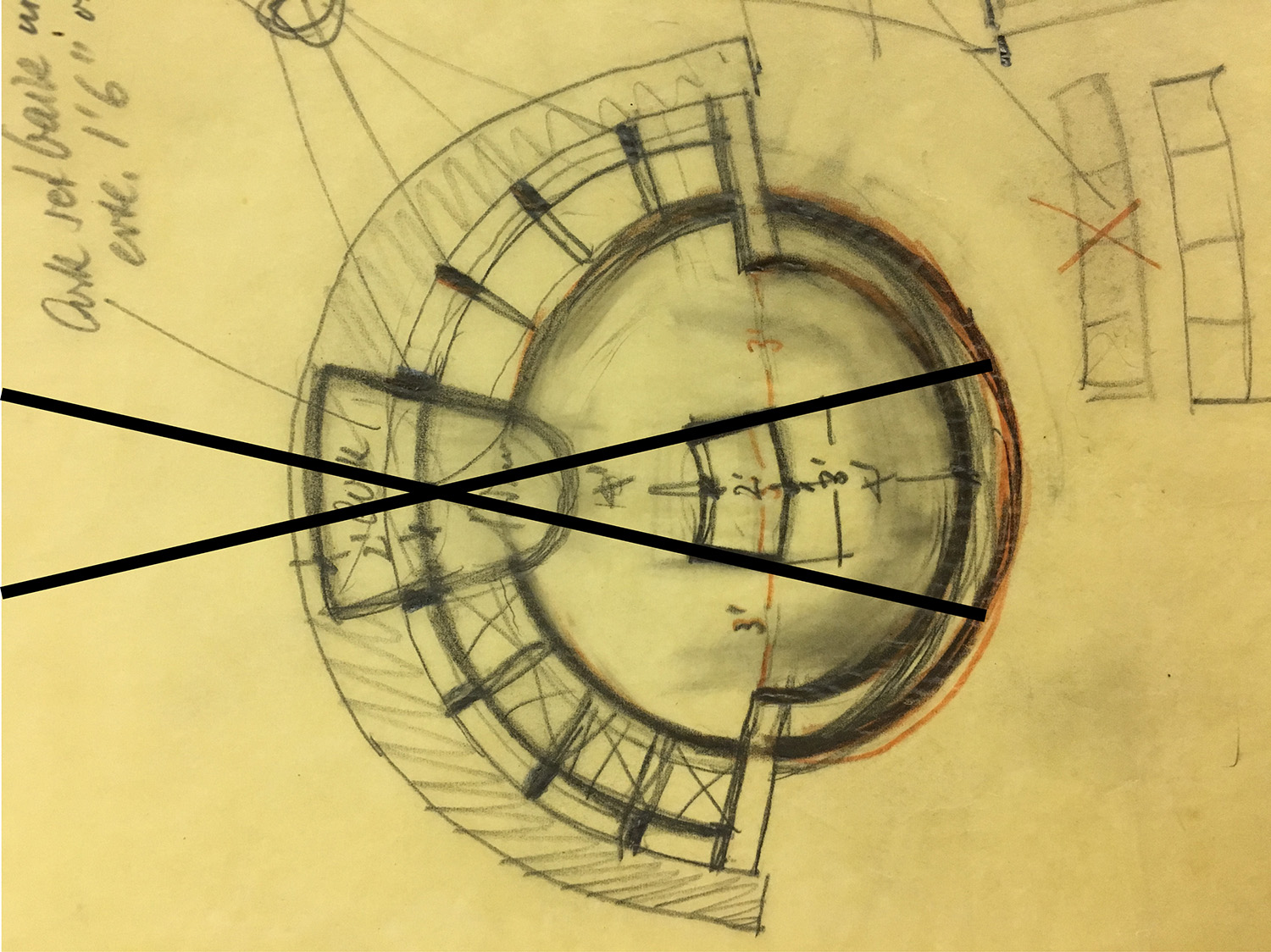

I noticed the performance on Carolee Schneemann’s CV with fascination, awe, and a bit of skepticism: “T.V., a Happening commissioned by NBC Television’s Tonight Show” in 1965, so early in her career, was surely a major event. Schneemann kept extensive preparatory notes and drawings and yet I could find no documentation of it in our archives. The 1965 “Tonight Show” mention, with its carefully phrased emphasis on commission rather than production, had fallen off lists in some exhibition catalogues and books, only to be added back on by the artist, time and again. And so, I added it to my very long list of “items to research.” After all, Schneemann’s history of ground-breaking performances is sizeable and her stories about those events legendary. And there is so much to uncover: What happened to the video footage of “Interior Scroll” from 1975? Who photographed the London performance of “Meat Joy?” Who reported the dramatic screening of “Fuses” at Cannes, in which moviegoers shredded their seats in outrage? How to trace the influences and anti-influences, how to parse an artist’s story from the stories of others who were there, and how to determine if one version should take priority? Incompleteness and indeterminacy are concepts that Schneemann was far more comfortable with than I am. Things were reworked, reperformed, rehung, re-edited; dates were changed, then changed again.

When I looked in the archives for information about “T.V., a Happening,” I came up short. But then I found this piece in the Miami Herald. Dick Schaap—the double-letters clearly were important to him—published a piece in January 1966 titled “Carolee and The Happening That Hasn’t Happened As Yet.” In it he describes how a “Tonight Show” representative called Schneemann and asked her to stage a happening on NBC. She made drawings, notes, a draft of the performance: “We set it up like guerrilla warfare, so that Johnny couldn’t really disrupt it.” But after several revisions, the “Tonight Show” cancelled it altogether. The fact that we don’t have a record of the plans for the kinetic theater (Schneemann’s term for her performances) doesn’t negate the event; the discovery of her description of it—to a rather condescending newspaper columnist, no less—gives us an idea of just how significant the opportunity would have been.

Looking through the drawings from 1964 and 1965 that remain with the foundation, I came across one that seemed to serve as a key for Schneemann’s preoccupations in those years and that would, I think, have informed any happening she created for television. It isn’t specific to the commission; I’ve yet to find that material. But it offers a list of actions that become a type of concrete poetry, a way of entering the artist’s working process, with or without Johnny Carson. Actions that, though unrealized, remained formative.

—Rachel Churner, Director of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation

The Miami Herald, January 22, 1966, page 7A.

The Miami Herald, January 22, 1966, page 7A.

Detail of page 7A: Dick Schaap, “Carolee And The Happening That Hasn’t As Yet,” Miami Herald, January 22, 1966.

Carolee Schneemann, untitled drawing, 1964. (c) Carolee Schneemann Foundation.

Hong-Kai Wang with Bopha Chhay

Violet quartz, honey, cinnamon & huanglien

*This text is the preface of ‘Frequencies: Violet quartz, honey, cinnamon & huanglien’, issue 2 of ‘Beacon – a pamphlet series in ten issues’ published by Artspeak (Vancouver, 2022). The publication is comprised of five texts respectively authored by Bill Dietz, Darla Migan, Övül Durmuşoğlu, Hu Shu-Wen, and John Pule.

It all began with the heart. I started having heart palpitations in the late summer of 2020. My heart would pound tirelessly. Sometimes I could feel my pulse beating from my temples, down my neck, and to my wrists. And sometimes I would walk down the street and feel my heart racing so fast that the rest of my body could barely keep up. My heart is a sovereign being, the inside-out of an out-of-body experience. I had an appointment where a cardiologist ran a full blood test on me and had me wear a 24-hour electrocardiogram vest. Nothing appeared to be obviously wrong. My gynecologist ensured me that my heart palpitations were a common perimenopausal symptom. I had the option to begin taking hormones or do nothing at all, and to live with the imminence of menopause. The Taoist priest I met with claimed my condition was a manifestation of visitations made by karmic creditors from my past lives. She advised me to chant Buddhist sutras and mantras daily to repent for my karmic debts, particularly the Heart Sutra.1 It was my Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) doctor K who I found to offer the most concise diagnosis. That is, my heart palpitations were a symptom of excessive fire in the heart i.e., “heart yang” as opposed to “heart ying,” the result of excessive fluctuant energy. In light of that, the treatment became a matter of how to “compose” this energy— in other words, to consider the various frequencies. To treat a heart that ‘bounces like a drum’, alongside acupuncture treatment, he prescribed the following combination of ingredients:

violet quartz 30g, honey 30g, cinnamon 1.5g, & huanglien (goldthread rhizome) 5g

Vermillion Bird Dan (朱雀丹) is a well-known prescription in TCM derived from the Taoist alchemical medicinal practice (丹醫). It is named after the vermillion bird, one of four divine symbols of the Chinese constellation. Also known as the God of Heart, vermillion bird, according to Wu Xing (五行)2 aka the Taoist five-elemental system, “represents the element fire, the direction south, and the season summer correspondingly.” This prescription Vermillion Bird Dan works to ground the fluctuant energy within one’s body: huanglien clears away “heart fire;” cinnamon warms up “kidney yang;” honey softens the medicine’s sharp taste and effect; violet quartz tranquilizes the nervous system and the mind. Dr. K spoke about the ways that TCM aims to organize one’s frequencies. As such, in my case, it is a matter of how to (re)organize and (re)compose those uncomfortable frequencies that pulsate from the heart and disperses throughout the body. One’s body has its own cosmology, and as the Taiwanese novelist Hu Shu-Wen writes “Every body is a planet with its own tides.”

Taking Dr. K’s alchemical organizing of frequencies as an elemental point of departure, Frequencies: violet quartz, honey, cinnamon & huanglien is a pamphlet comprised of five texts, each of which sets out to interpret frequencies expansively in relation to a perceived ailment, condition or bodily disorder. The prescription, anchored within the Taoist elemental system, aims to adjust at a molecular level the internal workings of the body, seeking to rectify and reclaim an elemental balance within one's body.

Grounded in our inquiry on “frequencies,” each contribution sketches out a cognitive constellation anchored within the body and its politics thereof. It is our hope that this focus would provide a way to open out to a wider social body and ideas of collectivity in different ways, whilst not overlooking ailments (often perceived as negative) and what is felt in the body. Furthermore, we want to think about how complex knowledge systems and practices pass through our individual and collective bodies, and how one participates in different systems of knowledge and care.

This small publication is as much for reading as it is for listening. The contributions offer personal stories and experiences of the way ailments reside in our bodies, something like a poetic repertoire. These contributions speak through the body it inhabits; some borrow the voices of other’s, while all living within a specific order of body politics. How does personal responsibility for one’s own well-being affect and contribute to collective well-being and vice versa? The contributions to this pamphlet reveal how compounding pressures impact our mind, body, spiritually, and the various ways we attempt to ease, live with, and challenge and upturn what ails us.

1 The Heart Sūtra is a popular sutra in Mahāyāna Buddhism. In Sanskrit, the title Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya translates as "The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom". The Sutra famously states, "Form is emptiness, emptiness is form." “The Heart Sutra,” Wikipedia, accessed December 8, 2021.

2 Wu Xing is usually translated as Five Phases, is a fivefold conceptual scheme that many traditional Chinese fields used to explain a wide array of phenomena, from cosmic cycles to the interaction between internal organs, and from the succession of political regimes to the properties of medicinal drugs. “Wuxing (Chinese philosophy)”, Wikipedia, accessed December 8, 2021.

back to home ︎

Hope Ginsburg, Matt Flowers, Joshua Quarles

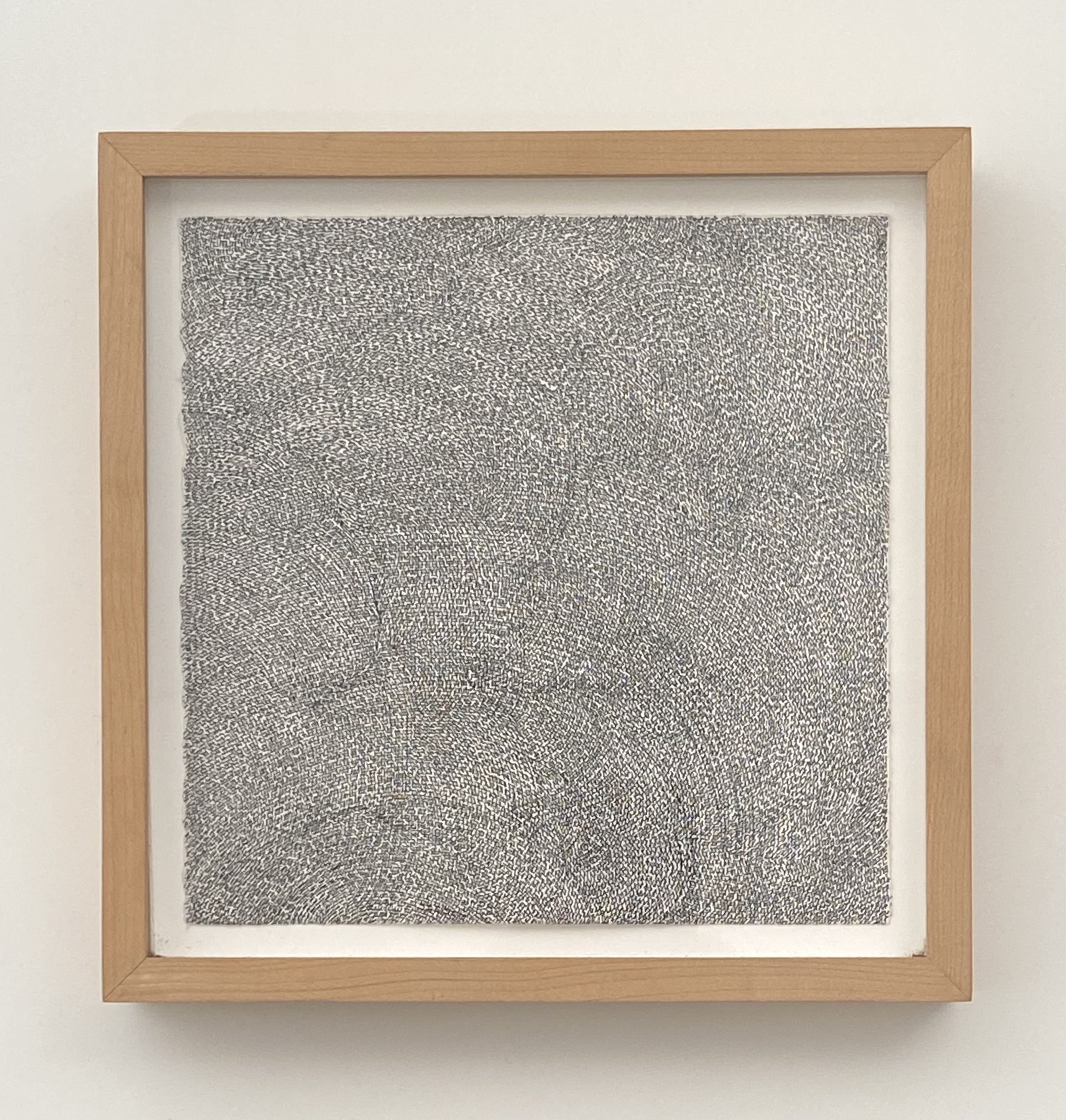

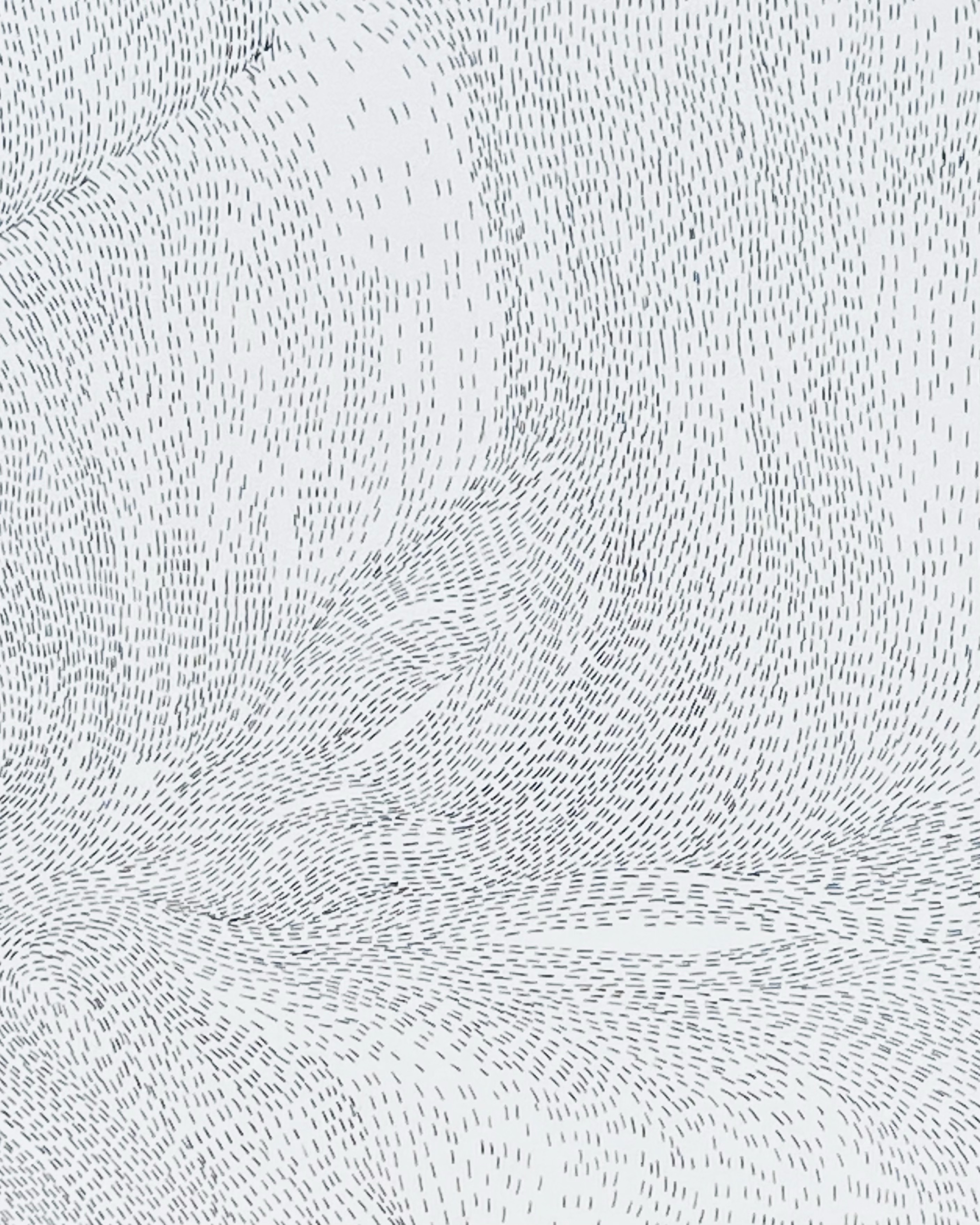

Swirling Postcard

Swirling Postcard, 2023, Single-channel video with sound, 3 min. 57 sec.

Swirling Postcard delivers a snapshot of the coral nurseries and outplant sites of St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, where we filmed our four-channel video installation Swirling (2019) in the summer of 2017, just before hurricanes Irma and Maria made their devastating paths through the Caribbean and Florida. “Postcard” visually updates Swirling’s coral restoration vignettes and offers a brief dispatch on the state of The Nature Conservancy in the Caribbean’s coral restoration initiatives in St. Croix six years hence.

Swirling took its name from the “swirl” of factors impacting the coral restoration story’s outcome, as well as from one of our shooting sites, the Swirling Reef of Death. The staghorn coral nursery “trees” and outplants at the Swirling Reef of Death were demolished by Hurricane Maria. Cane Bay, another of our original shooting sites, fared much better. Matt shot Postcard at Cane Bay, revisiting the same outplant sites and focusing on new staghorn coral colonies and the dome or “table” nursery structures that have replaced the tree design. The lower-maintenance tables are less susceptible to storm surge and breaking loose from the seabed, though they have not yet gone through a major storm. (The damaged table in the video was likely caused by a boat’s anchor, one of many challenges faced by coral reefs.)

Staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornus) is a focus of The Nature Conservancy (TNC) restoration efforts for several reasons. It is fast growing—though some might be older, much of the coral in the video is between one and three years old. The species is “weedy,” it comes and goes depending on water temperature, sediment, and fireworm presence. Fish and other wildlife love to make homes and hiding spots of staghorn coral; it is a habitat-builder. Staghorn coral is easy to propagate in water. If you break off a piece on the reef, it continues to grow; this is actually the coral’s natural life cycle, which lends the species to propagation. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Staghorn coral is not susceptible to Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD), which is devastating coral in Florida and the Caribbean.

TNC has launched several new coral restoration initiatives since we shot Swirling in 2017. In that year, the scientists began work on assisted sexual reproduction, collecting the coral’s eggs and sperm when they spawn once or twice a year. The spawn is brought back to land for fertilization in the lab, settling the gametes onto support substrates. These tiny larvae grow either in the lab or field nurseries from three months to a year, after which they’re outplanted to the reef. Unlike the work with Acroporids like staghorn, which is all cloning, assisted sexual reproduction increases genetic diversity among the corals, which is the only way to prepare them for future threats.

May of 2022 saw the launch of TNC’s Virgin Islands Coral Innovation Hub, a terrestrial lab carrying out underwater coral restoration in almost fifty acres of reef, and impacting three times that area of marine habitat in St. Croix. The lab affords the capacity to grow corals in tanks, specifically those that are difficult to work with underwater, such as boulder and brain corals. These slow-growing species are reef-builders, providing structure, strength, and shoreline protection. Another Coral Innovation Hub initiative is exploring new propagation methods like microfragmentation, in which corals are cut into small pieces to spur additional growth. The divers in Swirling Postcard are gathering fragments for microfragmentation in the lab.

The array of coral restoration actions described here is, without a doubt, cause for hope. However, in the words of TNC’s Lisa K. Terry, it is “just one small piece in a very big puzzle.” Climate change, pollution, coastal development, disease, and overfishing are all coral threats that are not addressed by restoration. If root causes like climate change and disastrous water quality are not tackled, restoration efforts will be in vain.

As with Swirling, “Postcard” flickers between optimistic and tragic. Healthy outplanted coral thrives, providing habitat for technicolor wildlife. The nurseries and outplant sites are portraits of labor between human and more-than-human beings for shared survival. But the scene is set in a reef that is a shadow of what it once was and could be. The repeated bell sounds in Swirling Postcard’s score call us to wake up, sounding a subtle yet persistent alarm.

Hope Ginsburg, Matt Flowers, Joshua Quarles

June 2023

Vast thanks to Lisa K. Terry of The Nature Conservancy in the Caribbean for welcoming the Swirling project over many years and for providing expertise and insight for this update.

Support for Swirling (2019) was provided by the Film/Video Studio Program at the Wexner Center for the Arts and Alumni Residency Project Support from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. The installation was exhibited in Sponge Exchange at the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum (2020) and New Earthworks at the Arizona State University Art Museum (2022).

Alina Stefanescu

Three Poems

Poem to First Love

How could I forget your sonorous touch, Sam?

When you fell upon me near the tree, I had no resistance

built up against love's virulence. In that moment, I was

novel. The first thou laid over my wrist like a stone

carnation, charming, unbearable. To be snapt and

yet sinking. Surely no one had yet been so thou to

you, as none had been thee yet to me. I was 17 and you

were giddying me towards the steamed encounter.

My family hated what loomed between us in dreams,

in dreaming—I was gone to them completely. Gone as

the swound, Sam. Spired in the gallop of your breath's

pacing. I don't think I ever came back; or — when it ended,

I was another person, a different sort of creature, this

raw, anticipative thing wrothed in having been read

though not written. Coleridge, would that we'd never

met! I would not be the lunatic of arcana, the raving

notebook of love's depravity, this Thee to your

Thou, betrothed to poetry.

--after Matthew Yeager

Dear B— would that you hadn't unlatched the symbols

When Thom Gunn admired

the hummingbirds giving blow-jobs,

he did so in a letter to a friend.

Gunn didn't drag their slim beaks

into the room of the poem where beards

and ears judge our exposed orifices.

I am over. Are we closer

now. I am assuming you know

of the pink whale I painted

on the cover of our shared notebook.

It needed marking.

It needed me to leave

the wee words and stroam

the alleys between vacant warehouses,

to heed the birdsong of idling trucks.

I think everything is beaked

if you let me touch it

amply. I wrote three

words on my wrist: alone,

alone, alone. Behind the

assembled dumpsters,

the cold hunch of green mettle

and the hundred-studded dandelions

raising their yellow pricks

to cover the meadow in eyelets.

Of Dignity

My husband is brilliant & statuesque

when he does not speak.

He poses like remorseless lede

on the ripped-up red chaise between towers of books & dead hydrangeas.

Some flowers don't smell when they rot, which reminds me

of Wittgenstein's Eastern Front diary — or the war between dying & writing

& masturbation, the question of suicide —

the way it just sits there.

That tweed hat on the floor

with its jutting lip, the hardness

of an I who'd rather touch you than it — the valor

drafted to fit the worn silence.

Brian L. Frye1

What is Called Legal Scholarship?

Two margarines on the go, it’s a nightmare scenario.2

We learn what it means to do legal scholarship by trying to do legal scholarship. But in order to do legal scholarship, we must learn how to do legal scholarship. So, by trying to do legal scholarship, we recognize that we don’t yet know how to do legal scholarship. What a conundrum!

Fortunately, lawyers do law, and therefore can do legal scholarship, if they learn how. But not all lawyers are capable of learning how to do legal scholarship. Legal scholars are as legal scholars do, and many potential legal scholars are stymied by their disinclination to do legal scholarship. Some lawyers are interested in legal scholarship, but uninterested in doing legal scholarship. Others try to do legal scholarship by doing law, which may itself be valuable, but is not legal scholarship.