Luke Dowd and Paul McDevitt

Dear Paul

January 6, 2019

Dear Paul

Thank you for sending me this new work. It’s great to see how cooled down you’ve become, frozen, gridded, squared off- like looking down on an ice cube tray. I often take the hand out of my own work so it appears like a machine made it. And in this case it has!

I’m struck by the flatness of the image. Artists like Broodthaers might be useful to look at especially in regard to the endgame of flatness as form of advertising, a sign-post to a conceptual position.

The title of Hama is seared into our retina and has a similarity to the Netflix ident. Have you seen this? First the screen flashes, clearing any afterimage. And then Netflix pops up- red- and if you close your eyes you can see it. It’s very clever. I wonder if it produces the same damage to your eyes like staring at the sun? Probably not.

In this representation, the ground that the image sits on is pink. Am I supposed to see this part? If so, then the internal ground, coloured a very pale green, invokes a feeling forestry, a naturalness and reference to the origin of the paper: trees. And then the blue, like the ocean, adds the other component: water. Hama is red like fire. It’s nice to see you covering the elements!

Regardless, I feel the pink is a stand-in for white. It’s interesting because recently when I was scanning a piece of ‘white’ paper when reproduced it also turned pink. It was as if the machine registered a colour we usually take as white. By exaggerating this you’ve colluded with the machine like wanting to merge with a printer, and shouted out, ‘I can be like a machine too!”

The illusion of the lifted page in the lower right corner reveals another thing. In the “clip/edition” section it is backgrounded with, I think, a reference to glass but somehow it feels oceanic in the style of the reveal, i.e. that which is “underneath” the paper, and I mean this in the Freudian sense- that sense of being with the world before being separated from it like breastfeeding. I wonder if this a bit idealism on your part? Are we ever with and fully connected to our artwork? I would say not. They are Easter Island statues. Mute! Impenetrable! Not like the ones in Night at the Museum.

The verticality of the composition mirrors the verticality of the support. Have you been looking at Chinese scrolls recently? Or Brancusi’s endless column, and more to the point his bird in space with the elliptical top slice, a focal point, the masthead saying in this case: Hama. Like the New Times masthead “All the News That’s Fit to Print”, it is authoritative and totalitarian. Artworks should be brutal so please don’t take this the wrong way. It’s politically exclusive but also fictional and playful.

I think the fonts could use some expansion. And putting barcodes on things now is just a cliché. We know…

Best,

Luke

March 12, 2019

Dear Paul

We touch with our eyes; our eyes penetrate this body-this artwork. Our eyes act as tactile registers and we caress it. Our touch sense is acting through our eyes.

When we don’t understand a painted surface or a surface, generally, we want to touch it to understand it. I don’t need to touch this artwork to understand it. I’ve seen, I’ve touched, and at some point, even made artwork that have this tactile register.

The first registration is texture then image. In the same way we acknowledge words before we read them. But the digital is confusing this because, as a format, it seems to be not there but like canvas or paper it is just another texture that at times simulates texture. The digital screen is an empty vessel, a clean empty glass.

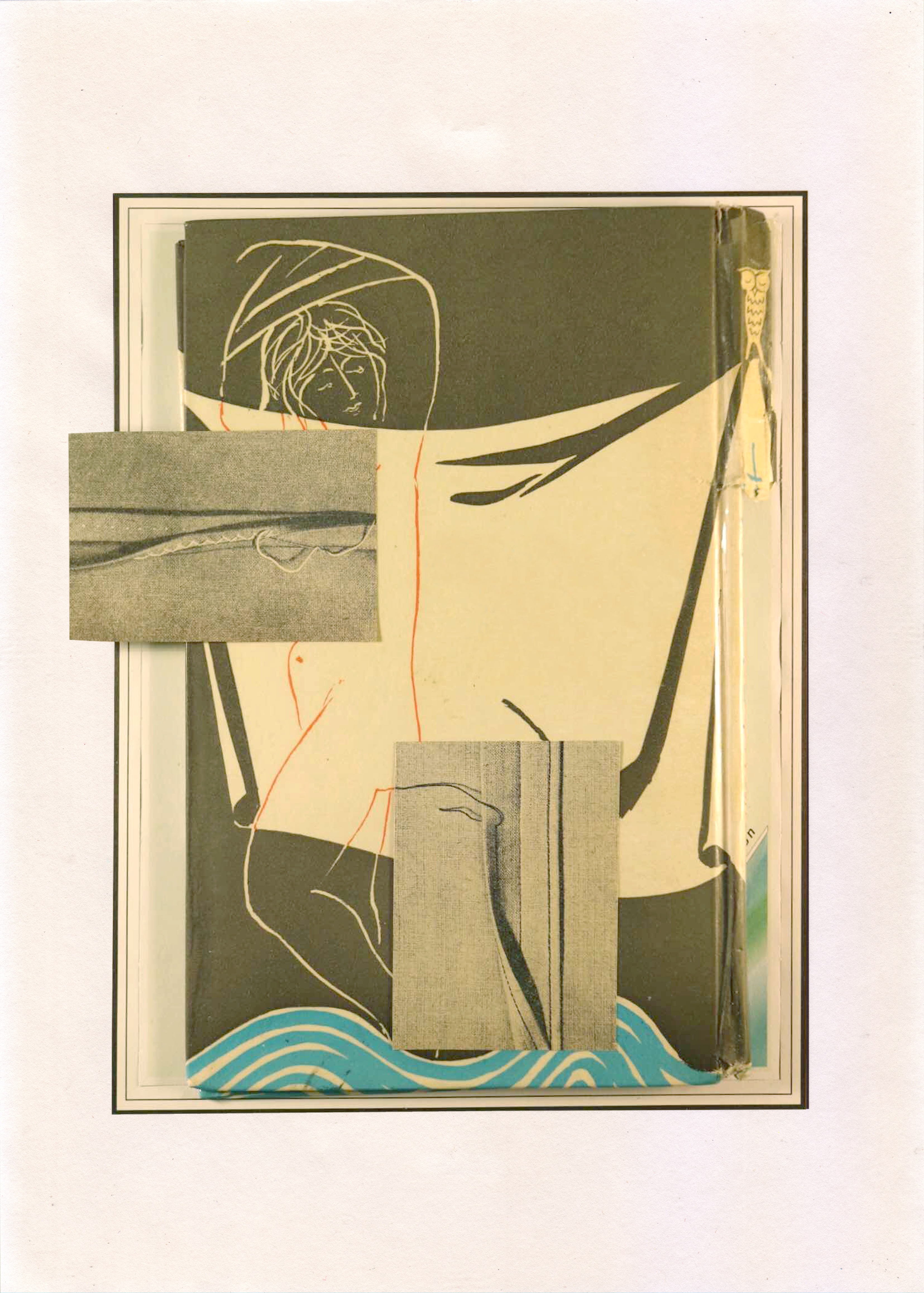

It’s great to see you moving away from a flat plane with the illusion of depth and develop the whisper of Montage. Montage whispers: I’m not real. I was distinctive parts, a collection of objects, but now I am compressed-flattened.

I’m immediately reminded of synthetic cubism. And then I think about this passage from Bad Boy by Eric Fischl, “My mother’s death left my family in tatters. We were a disparate group to begin with….and when a family bonds around an illness, as ours did, you never have the chance to explore and develop other reasons for staying a family. So when our mother killed herself, she released us from our struggle, from what held us together as a family- our common plight, our shared purpose.”

Inevitably, there is falling that happens when forms are broken but lines continue- when you morph line to form. We are falling in the space between- like the space between the monkey bars when we let go of one and before we catch the next. It is that falling that we need in every artwork. It is the imagery space that is not solid but that which are propelled within. It is exciting and has that subjectivity that comes with abstraction that makes it exciting (and disappointing) to experience. We have a feeling of falling, yes, but we are trapped within a composition that is fragmented but continuous and compelled to ask with shaky eyes, “Is this it?”

There is something light here. It is not the ghost of Carlos Casagemas. nor is it the trauma of the suburbs. A woman at the beach in front of a towel together or are you making a face like Kuniyoshi or Arcimboldo? But am I seeing this right, as I get older and collapse the space of abstraction that was once fantastical, open, wild with hope and possibility into the pragmatic limits of figuration?

Best,

Luke

January 23, 2020

Dear Paul

I’m sorry it’s taken me so long to respond. Initially, I was a bit thrown by this image. It felt a little Albert Oehlen, in a bad way. It made me uncomfortable- too Coca Cola, too Great American Nude- so I put it aside and then something took my energy into another realm which I am now only coming out of.

I fell into another conversation which became a sort of relationship and then as quickly as it came it ended. I once said, ‘I am in love with the idea of you’ which took them by surprise. I’d said love too soon (it was the IDEA of you!) and that was the beginning of my journey on a winding dirt road, dangerously above a rocky gorge that I would eventually steer into.

I said relationships are like poker matches: we ante up (you put 5 in, I put 5 in), and that’s the only way they are like poker. They didn’t like that either. Nor this: there is an aspect of relationships in which we lose ourselves, become permeable and impressionable. But it was me who got lost, impressed upon and permeated. I ended with as much form as a wet washcloth. By the end I didn’t know whether I wanted butter on my toast or not.

We might say that artworks are permeable, permeable by the language that surrounds them, our projection that ensnares, traps them. But it’s not true. We are the permeable ones. Approaching an artwork like a dry stiff towel, it can be difficult for our fabric-like pores to begin the process of absorption. It can be a slow. But then it happens. The moisture comes in and then un-noticeably, is breathed out; it goes out through the pores and orifices it entered and is just itself again, unaffected by both entering and exiting. It is still the same. They are given form, constructed, become visible and are as permanent as our breathe on glass.

Artworks, like water, are in a hydrologic cycle.

Best,

Luke

P.S. I recently got up in the middle of the night and saw a fox digging in my plant pot and knocking it over (again). Ah, I thought, it is you guys. And then I wondered do you, foxes, come out every night and say to yourselves, “What the fuck did they do now? Everything’s all moved around again!”

August 1st, 2020

Dear Paul

Thank you for this response. I hope you are keeping well, and safe.

What’s interesting here is the pull, the patterning of things that are ultimately different. Our differences are overridden by matrixes that cluster our similarities, like Richard Prince celebrity-likeness photos or internet memes that liken the Trump gang to pop culture villains, and this removal by sun bleaching has given these two distinct artists a similarity, although I often think that Kandinsky has a figurative bend like Miro.

This collapsed salon hang re affirms similarities, as if the spectrum of these classical modernists is pretty narrow, the plasticity of modernism is a short menu.

The proportion of the canvas is driven by the borders of the collage, it is almost square, Instagram ready but not quite. Usually, we start with a canvas size but here you frame and determine canvas proportion by the contents. It can be anything, any size- your image has the flexibility of a rubber band.

The canvas is glass, plastic, light. Ironic because Chagall made a series a stained-glass pieces. The glass of my computer screen is safe, like safe sex, like a socially distanced (with mask) encounter.

Social distance has always existed in art. We are cordoned off, sometimes separated by glass. If we were to touch it in ‘in real life’, we would do so with gloves or freshly washed hands. We sneeze away from the picture. To be safe, we touch with our eyes. But these images, the images in this conversation have virtuality. They are glass. They are rubber bands that can be stretched visually, they hold the pencil lead and can just as quickly be erased. What was once an impression and smudge on the paper is now wiped clean off our retina like the flicker of a strobe light. Now that’s an efficient rubber!

When Victoria Park, across the street from me in London, re-opened after closing for two weeks during the Covid-19 Lockdown, there were social distancing measures and rules in place. Keep your distance, no clustering, no sitting. And with these rules, I thought about art practice: the art market and its trends and how we as artists develop making sense of our work in relationship to others.

We move as if pulled towards each other, to collect in the generative sense, to become collected, to be part of something. And now we are asked to move away from each other.

In art we glide alongside other art, sometimes knowingly and sometimes not. Our work makes sense to ourselves in this proximity. We pull towards. We pull away. We are caught in gravitational and magnetic fields. When we are released from the hold of others what happens? When we are not constellated and clustered?

Victoria Park hired new rangers to enforce these rules and with bullhorns they order out: “Don’t sit, keep moving, don’t cluster”- and I thought- good for art.

Responding to an audience question, In the Bennington Lectures, Clement Greenberg said, “I haven’t met an artist yet who admired De Kooning in the 1950s who came to anything in his art, and there some prominent artists around now who admired De Kooning. But, they haven’t come to anything in their art, I don’t care how well known they are…De Kooning led a generation lost to New York to their doom…”

It is unfortunate that we are always in the process of identification. As much as we try to run away, we always seem to get locked back in- we can’t escape ourselves and this is both our comfort and our cage.

Best

Luke