Sam Rosner

In the Plantation Cemetery- The Meet

We met in the parking lot of Sal’s Pizzeria in Fork Union, Fluvanna County. The morning had a slightly cool edge to it, the beginning of September in Central Virginia. I drove against traffic, heading along the rural roads that connect 64 to the southern parts of the county. Somewhere on the road behind me was a van full of sleeping students, a group of Honors College students from the University of Liberia who, over the course of the last few years, have been searching for a language with which to identify, preserve, and design the cultural landscapes of their home, Monrovia, Liberia. We were all meeting with a group of architectural historians whom we were joining on their mission to 3D scan the Bremo Enslaved Chapel. In the concrete, pock-marked field that approximates a parking lot, the team stood out like a sore thumb - wearing sun hats, heavy duty hiking boots, and long pants to protect against ticks. They were cheerfully swapping stories about their summers spent exploring historic Virginia buildings, travelling around Paris, Delhi, Rome. Shaheen Alikhan, a master’s student in the UVA Architectural History program excitedly pulled out her phone to show me a 3D scan of a wall, graffitied sometime in the 16th century by Michelangelo. “They just let me climb right up there! No security or anything! And it’s just there!”

We waited in the parking lot until a large black van pulled in. The driver, popped out and walked over to the sliding door, pulling it open to reveal her groggy cargo – 7 students and their two professors, as well as Kristan Pitts, a UVA planning student and pastor- meeting on this warm morning in a very quiet corner of Central Virginia. Allison James, a Cultural Landscape Preservationist and consultant for the World Monuments Fund has been coordinating between the University of Liberia and the University of Virginia for the last few years. From the last few days that I’ve spent shuttled around Washington DC and Petersburg, VA with Allison, I can say with certainty that she is a force of nature. Anyone who can manage to get a group of 13 from the National Mall to Union Station in time to catch a train without leaving anyone behind surely deserves some kind of medal.

The group climbs out of the van, stretching their legs. Sleepy-eyed, but not for long. This group is hungry to get started. They know that their time here during this trip is limited and they’re not missing a single minute. They snap to attention as the whole surveying team calls us to order. We receive our directions: we will be caravanning out to the former Plantation where we have received permission from the current landowners to enter. Will Rourk, 3D Technologies Specialist for the UVA Scholars’ Lab, a broad man, in his blue forerunner will lead the pack. Once we are there, we will first enter the cemetery then walk to the chapel. We break off into our car groups and line up to begin our day, peeling off onto the street.

I spent my summer travelling along rural Virginia roads. In Albemarle County, that’s most of the byways that aren’t 64 (Staunton to Richmond) or 29 (Charlottesville to DC). I was part of a research team called “Finding Virignia’s Freetowns,” a multi-disciplinary group whose goal was to 1) identify the probable locations of historic Black Freetowns 2) map these on ArcGIS, and 3) meet with descendant groups to begin to tell the stories of these quickly disappearing places, and 4) adjust our definitions of Freetowns given our better understanding of who they served and why they existed in the first place. For me, I defined Freetowns as:

Freetown (noun) – a loosely-bounded, geographically-specific community of Black landowners and tenants that arose in the American South around the mid-19th century and in the years following Emancipation until about the mid-20th century. These communities were often created from the cheap sale of land by Plantation owners to their formerly enslaved people. They typically have a church and adjacent Black school at the center serving as a rural common. Freetowns are notable for being thriving rural centers of Black commerce and often include farmers, blacksmiths, railroad workers, general store owners, as well as domestic workers who work in the surrounding white households.

Studying rural lands is difficult. What I had taken for granted walking around cities – public access and a general understanding of where I can and cannot enter – was less clear in the countryside. Streets here are either public or private, marked by posted signs warning off trespassers. Given the longstanding tensions between the University and its surrounding areas as well as a general distrust of outsiders, we stayed along the main roads, pulling off to sneak peeks at rivers, small grave plots, and churches. Back in our studio, we dove into the past to try to understand the present ground conditions.

We developed criteria for identifying these Freetowns. Using maps from 1870-1940, which notably marked the separate racial institutions in the counties, we geolocated Black schools and churches and then checked these locations against census and property tax records to draw a rough radius around them. Street names also provided key clues as to the people who had lived in the areas. We created a cast of characters, and we used the sparse information to guess at their lives. Through the census, I saw families expand and contract. Babies were born and grew up to be husbands, wives, fathers, mothers, grandparents. Where names disappeared, we hoped for the best. Cemetery headstones in church graveyards began to match up with enumeration records. On Browns Gap Road, the main artery of Northwest Albemarle County, named for the Welsh family who had carved up the Shenandoah Mountain hollow with tobacco and wheat fields, we could finally see beyond the thickets of tulip poplars and hickory-nut trees and gaze into the past.

Now, driving along James Madison Highway, we finally turn right onto the private gravel road of Bremo Farms Lane. The road was flanked by bright September meadows, shining yellow with early goldenrod. At the woods edge were jagged stumps, the index of a recent clear cutting. Dust rose around us as we headed into the woods. We reached a metal gate that was attached to a dry-stone wall. In the Virginia countryside, stone walls are key indicators that you are approaching an antebellum site. The stone that comprises these sturdy perimeters is slate, sourced from the surrounding land. It was likely hewn and stacked by enslaved hands. The blue Forerunner flashed its brake lights and Shireen bounded out of the passenger’s side to pull the metal gate open. We proceeded through the iron gates and into the fields.

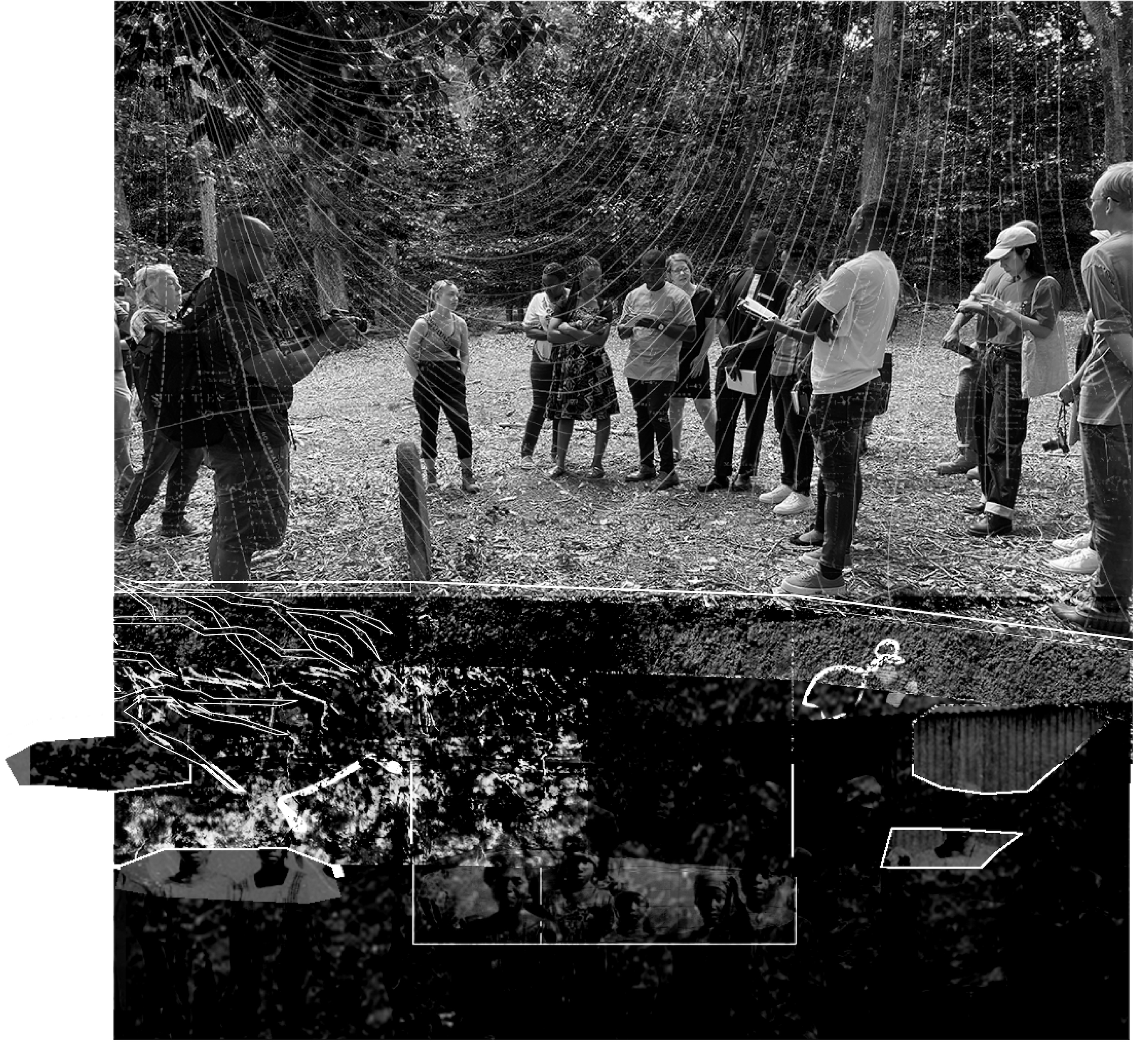

- In the Cemetery

Any morning chill had left at this point. We pulled along a grass embankment in front of a machinery storage pole building. In our eagerness to set off, we realized that we had yet to make introductions between the various groups who were brought together here, at Bremo Farm. Allison, by this time used to explaining the Field School, launched into the history of her collaboration with the University of Liberia’s Honor College students. Each member of cohort steps forward and introduces themselves, their words imbued with deep gratitude and a solemn understanding of their deep historical roots which are buried deep within the Virginia clay: Dr. William Allen and Ms. Lorpu Blackie (the professors), Gayflor Wesley (the geologist), Thomas Gmawlue (the engineer), Harriet Gaye (the social worker), Alexander Dash (the biomedical scientist), Lorpu Flomo (the future doctor), John Delphin (the economist), and John Lissa (the investigator/schoolteacher).

Next, the historic preservationists begin their introductions. They are a group of faculty, librarians, and students who have been drawn to key Virginia sites such as Monticello, Montpelier, and now, Bremo. Will turns. He gestures toward two members of the survey team, and they introduce themselves: Tricia Johnson, the director of the Fluvanna Historical Society and Horace Scruggs, retired music teacher and history buff. Horace and Tricia are both warm, they’ve been eagerly awaiting the Liberia group. They welcome us and we express our gratitude.

Horace Scruggs is a tall, African American man who looks much younger than he reports. He’s dressed in cargo shorts and hiking boots, the unofficial uniform of the historic preservationists. He wears a DSLR camera around his neck. He speaks with the clarity and gravity of a former schoolteacher.

“We are standing on the threshold of the Bremo Plantation, the long-standing estate of the Cocke family.”

To the south of us flows the James River. The Appomattox River, a tributary of the James, flows past Pocahontas Island in Petersburg, VA, the former home of Joseph Jenkins Roberts, the first president of Liberia.

Horace Scruggs gestured towards the woods, “It is on this land that my ancestors were enslaved. We will pass through the stone fence and onto the hallowed ground of the Bremo slave cemetery. Walk softly.”

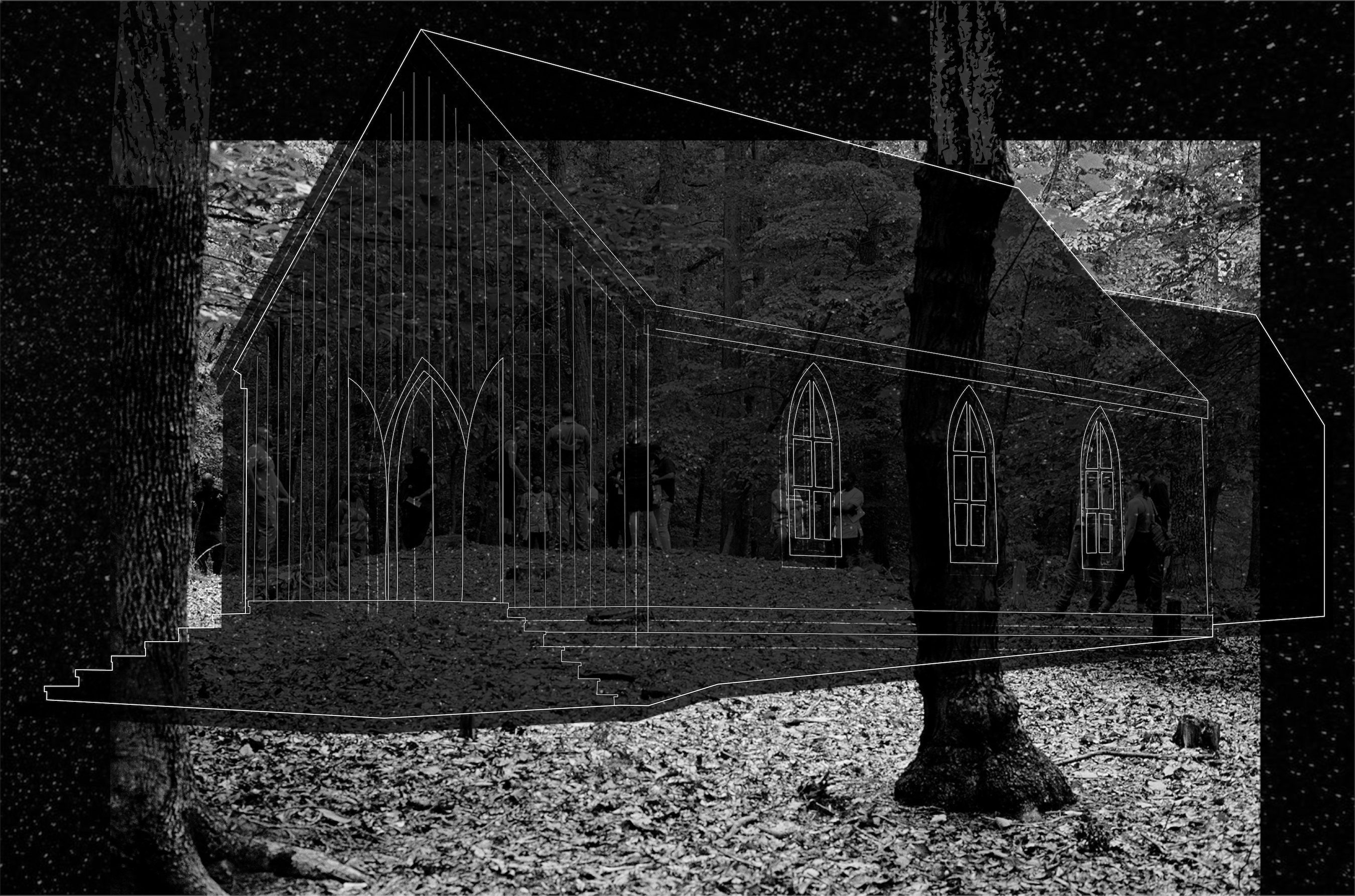

The ground is thick with leaf litter. The woods are new growth and little to no under canopy impedes our path forward. Scruggs tells us that in the 19th century, these woods would have been cleared and used as pasture-land. From both the cemetery and the slave chapel, the only one known to exist in Virginia, there would have been clear views to the main house. Today, all we can see are thickets of oak and hickory.

The group fans out. As far as enslaved cemeteries go, it’s remarkably well preserved. The boundaries of the yard are clear. Dry-stacked slate lines the perimeter and tall, hewn, columnar stone forms the gateway. The interior of the cemetery has a few trees, but large stumps show that the cemetery has been kept with light clearing, creating thresholds of light and dark. Most of the headstones are informal but present. Many are slate, cut with handsome straight lines. If their faces bore names, they have been worn away by lichen, rain, and time. Here and there, young holly shoots poke through, attempting to make use of the canopy breaks.

I didn’t see it right away; it was set apart from the other burial plots. The stone rose like a glacial erratic from the cemetery floor. The stone was slightly askew, with a clean, handsomely arched top. It looked to be granite, deviating from the surrounding slate. As I walked closer, another aberration became clear: the stone held a name.

Gravestones in enslaved cemeteries are typically not carved with names and dates. In the cases that headstones are erected to mark the deceased, the loved ones would leave the stones blank, as writing posed a significant risk for the living. In the early 19th century, white slaveholders heard reports of organized slave revolts led by educated, relatively mobile enslaved men and women, such as Nat Turner’s rebellion in 1831. The fear sparked by these movements became codified and prohibitions against preaching by free Blacks and teaching enslaved Blacks came into law. To write a loved one’s name into stone meant risking severe retribution.

This fact brings us to another one of the peculiarities of the place.

Bremo Plantation is the former estate of John Hartwell Cocke, a friend of Thomas Jefferson and a brigadier general in the war of 1812. As far as plantation owners go, Cocke is complicated. Among that cohort, he held a progressive belief that “slavery is the great cause of all the chief evils of our land… a cancer eating upon the vitals of our commonwealth.” Despite this strong distaste for the institution of slavery, he was also fearful that a purely emancipatory approach would result in a dangerous situation in the Southern states and that White and Black people could not cohabit within the country peacefully. This double consciousness is at the foundation of the American Colonization Society (1817 – 1904), the organization formed “to transport freeborn and emancipated American blacks to Africa and help them start a new life in the “land of their fathers.”

Though he was an early member, Cocke waited until 1833 to emancipate one of the families enslaved on the Plantation, the Skipwiths. This delay could possibly be attributed to Cocke’s tendencies towards meritocracy. Although he knew that slavery could not persist, he felt strongly that he could only emancipate those who showed that they had the strong moral fiber and Christian work ethic that forming a new American colony in Africa would require of them. With this clear goal in mind, Cocke defied antebellum norms and created an educational and vocational program which resulted in the training of skilled craftspeople whom Cocke hoped would be useful in their African conquests.

Johnson reminds us that these skills would also have resulted in a higher sale value of the enslaved themselves. When weighing men like John Hartwell Cocke, the scales of good and evil never seem to balance.

By now we’ve fully circled the grave. Scruggs draws our attention back to the stone. He asks us to look closely at the script: “Ben Creasy.” The B and C are in a large, beautiful, Gothic script, with a double stroke of the primary lines and a dramatic serif. This stone was lovingly carved and performed by the careful and skilled hand of Ben Creasy’s son, a trained stonemason. A chill runs up my spine and I seem to know what Scruggs is going to say before the words form in his mouth, “Ben Creasy is my ancestor.”

There are only a few moments when one can appreciate the thickness of a site. I’m jolted by the familiarity of the name. Creasy of Creasytown, a “Freetown”. The connections between my summer spent searching through archives and driving along country roads and the week I’ve spent in the Field School clarify. I began to step back while Horace reads a letter written by one of Ben Creasy’s sons to a brother, instructing the family to act in accordance with their late father’s values. I wanted to take in the whole scene.

Tricia hands Thomas the book, “Slaves no More, (1980)” a collection of letters written by Liberian settlers to their former masters and master’s families back in America. A page is marked, a letter from Peyton Skipwith, the first emancipated man from Bremo Plantation to be sent to Liberia, to John Hartwell Cocke. Thomas Gmawlue has the heart of a poet, and we are called to attention again.

“Monrovia, Liberia, February the tenth, 1834

Dear Sir: I embrace this opportunity to inform you that we are all in moderate health at this time hoping that these few lines may find you and yours enjoying good health. After fifty Six days on the ocean we all landed safe on new years day.”

Could Ben Creasy have ever dreamed of this moment? Could he have imagined this congregation of people, of family members and long-lost loved ones, gathered at his final resting place. Could he have imagined this bridging of oceans of time, oceans of suffering, oceans of history. Gmawlue read on, his Liberian accent inflecting Peyton Skipwith’s words with the warmth that two centuries of expatriation would give to his ancestors.

The fact of our presence, standing here together, is reason enough to believe that there is hope for the future. This group of students travelled across the Atlantic to return to Virginia in search of connections and networked histories embedded within our shared cultural landscapes. At this place they found traces of ancestors who survived bondage and endured the difficulties of building a country. We did not talk about it, but a brutal and bloody Civil War marked the childhoods of many of Liberia’s youth. 20 years later, these students – Thomas Gmawlue, Alexander Dash, Gayflor Wesley, Harriet Gaye, Lorpu Flomo, John Delphin, and John Lissa- are picking up the pieces and are looking towards the past to rebuild their country in a way that acknowledges the complexity of Liberian identity.

The letter comes to a close. Gmawlue reads the last, brief sentence from Peyton’s first correspondence as a Liberian, “Direct your letters to Monrovia.” We will heed this direction. Our work together is just beginning.