Abigail Child

Ethnography’s Excess

It is perhaps worth remembering that the impetus for collage is from technology and from mass communications, beginning with newspapers from the 19th century on, with their adjacent pages and columns, allocating space to the time of the commuter’s passage to work, to her or his “read”. Thus, work outside the house and printed news—i.e. new forms of labor and information under industrialization with its ability to swiftly reach people across space— combine to underlie what we might call a collage culture.

I grew up within that culture: of the picture magazines, LIFE, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC, the articles switching from country to country, face to face, colonialism to cereal to physics to war. I grew up as well with television, the prodigal exemplar of switching, tuning, changing, channeling content and advertisement. Given this world, and indeed the global world of the internet, of course we glean, we scan, we scavenge, we collage.

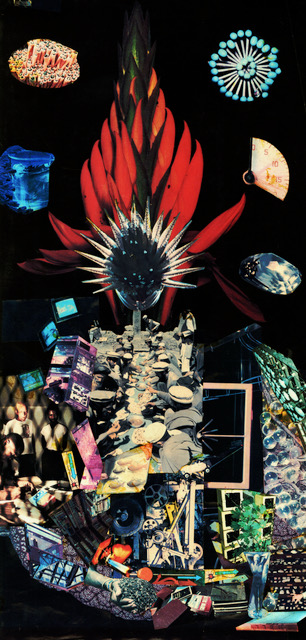

Figure 1. GANGLIA

I have always been interested in excess, what doesn’t come clean. Not the perfect image, but the messy one, the left over, the inordinate, the extraordinary, the scrappy. Not the monumental unity, but the pieced. Not random, but maximal and inclusionary.

“…. What shape does an engaged politics assume in an empire of signs?”

Fragmentation of the image-object invades and evades, the human body is spun and punned across the page. Melodrama relies on intensity and mystery, takes on Sisyphean humor while patterns emerge: of wheels, faces, conundrums, colors. The connections shape a medley of relations, the images acting as free radicals, reaching rhizomatically into the life of other image-objects to build another, impossible? world, a soft architecture of the imagination. Where eyes pass through thresholds to new doors, nuns’ habits become stars in an alternate sky, Arab men feast before a garden in front of a prison. The layers of meeting and meaning proliferate: magnetic, recognizable, estranged, communal.

Figure 2. PLUME

Simultaneously influenced by and eliciting the surrealist Americanism of a Bruce Conner, the cut-and-paste gestures of Hannah Hoch and the sensuousness of color and intensity of the abstract expressionists, these collages are alive to the makeup of the social body. None of these works are works of nostalgia— neither for the 1950s nor family. They are not send-up’s, nor satires of famous Hollywood features, nor adoration of mythic heroines, nor mourning for the dead. These are image worlds built out of refuse, out of the tossed, marginal and kitschy, jumbled, upside down, topsy turvy, gleanings from the mainstream, savings, salvage.

I give myself “obstructions.” This collage will only be made out of triangles, this one structured by color, another only of complete objects or products. In the process I begin to understand the overall figuration of paintings by Bosch, the limits of the page and influence of size, how the process parallels my filmmaking: that moment when every piece ‘suits’—and the next, where it all falls apart. The attempt: to structure the mind’s heap of image-eyes—to re-play/reread/re-arrange the industrial/capitalistic landscape of images flowing to us via the net, social media and media in general. To create amidst the swiftly changing accelerating welter of beauty and information in the contemporary. Not to return to landscape, not to sexual exploitation, but to swim in and twist, “bust” the flow.

Figure 3. NEBULAR

The eras’ modern and now postmodern, post-internet citizens of the 21st century have exhibited a previously unimaginable capacity to cope with the discontinuous, in aesthetics and in our physical, as well as virtual life. We live in a world cluttered with things, so it is a necessity to go behind them, underground, surround them, to locate sources, transmutations, asymptotes— so as to re-contextualize and upset the usual associations— rather, to underline hidden meanings, refresh their vitalities and irresolution.

Questions remain: has digital simply increased the ephemerality of our collective images, even as it has widened the availability and use of same in art and in the commercial spheres? Are we living in TOO MUCH-TOO MUCH to quote the artist Thomas Hirschhorn? Are we connecting everything, because we sense that we are lost, we are frightfully disconnected in the first place? Or as Vilém Flusser suggests— is it that

Human beings forget they created the images in order to orientate themselves in the world. Since they are no longer able to decode them, their lives become a function of their own images: Imagination has turned into hallucination.

Figure 4. NEW MODERN TIMES

Yet for artists who live in the saving/savaging that art-making is— we continue to refigure, and refuse, excavating objects and emotions, remaking relations to confabulate a future—transmuting hallucination (back?) into /and through imagination— reshaping our visualized world into a constitutive and comic realization.

New York City/ Staatsburg NY

May 2021