John G. Hanhardt

Nam June Paik in Performance

(1)

Born in Korea in 1932, Paik pursued his early interest in music at the University of Tokyo, where he wrote his thesis on the modernist composer Arnold Schoenberg. Paik moved to Europe in the late 1950s, following his interest in the avant-gardes emerging there. Soon after arriving in Europe, he met the composer John Cage and George Maciunas, the Lithuanian-born entrepreneur of the avant-garde who founded the Fluxus art movement. Both inspired Paik to challenge the aesthetic forms and materiality of art and the conventions of art exhibitions. As early as 1963, he had a one-artist exhibition at the Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, Germany, where he showed an array of manipulated and interactive televisions and audiotape pieces alongside dismantled and reconstructed pianos. It was a landmark exhibition and signaled Paik’s ability to create events, performances, and objects that opened a new path for artists. Paik’s performances and actions across Europe were gaining attention. The composer Karlheinz Stockhausen’s description of Paik performing his composition “Simple” conveys something of the experience of watching him perform: “Paik came onto the stage in silence and shocked most of the audience by his actions as quick as lightning. (For example he threw beans against the ceiling, which was above the audience and into the audience.) He then hid his face behind a roll of toilet paper, which he unrolled infinitely slowly in breathless silence. Then, sobbing softly, he pressed the paper every now and then against his eyes so it became wet with tears. He screamed as he suddenly threw the roll of paper into the audience, and at the same moment he switched on two tape recorders, which was a sound montage typical of him, consisting of women’s screams, radio news, children’s noise, fragments of classical music and electronic sounds. Sometimes he also switched on an old gramophone with a record of Haydn’s string quartet version of the Deutschlandlied. Immediately back at the stage ramp, he emptied a tube of shaving cream into his hair and smeared its contents over his face, his dark suit, and down to his feet. Then he slowly shook a bag of flour or rice over his head. Finally he jumped into a bathtub filled with water and dived completely underwater, jumped soaking wet to the piano and began a sentimental salon piece. He then fell forward and hit the piano keyboard several times with his head.” (2)

Paik’s actions were inspired by the context of the site and the moment and what he felt would work. His performances were direct, playful, and confrontational, all distinctive features of Paik’s artmaking and exhibitions. For Paik, there were no protocols, and within every action/performance/installation, there was room for anything to happen.

(2)

To Act is to snatch from anxiety certainty. To act is to bring about a transfer of anxiety. (3)I want to focus on a couple of actions taken by Paik and suggest how they speak to the challenge of a contemporary art practice in our time of renewed technological change and the ongoing threat of the pandemic. The first piece I want to discuss is from 1960: during a performance at the Atelier Mary Bauermeister in Cologne attended by John Cage, Paik leapt off the stage to attack Cage’s necktie with scissors. It was an act that alluded to his effort to break free of his dependence on his teacher. Many years later, I visited Jean Brown’s home, a former Shaker seed house in the Berkshires, to see her collection of Fluxus art, which later went to the Getty Museum. Brown showed me a drawer full of ties cut in half – the Paik-Cage tie-cutting encounter had become a celebrated relic of the avant-garde. After Paik passed away in Miami in 2006, a final “cutting of the ties” was performed at his funeral at the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Home in Manhattan. After the eulogies, Ken Hakuta, Paik’s nephew, announced that the ushers were passing out orange-handled scissors. He noted that for anyone wearing an expensive necktie, “it was too late,” and the crowd laughed. On the count of three, each person with a necktie was asked cut it off, and that ended the program.

(3)

I am tired of renewing the form of music….I must renew the ontological form of music…. In the “Moving theatre” in the street, the sounds move in the street, the audience meets or encounters them “unexpectedly” in the street. The beauty of moving theatre lies in this “surprise a priori,” because almost all of the audience is uninvited, not knowing what it is, and why it is, who is the composer, the player, the organizer—or better speaking—organizer, composer, player. (4)

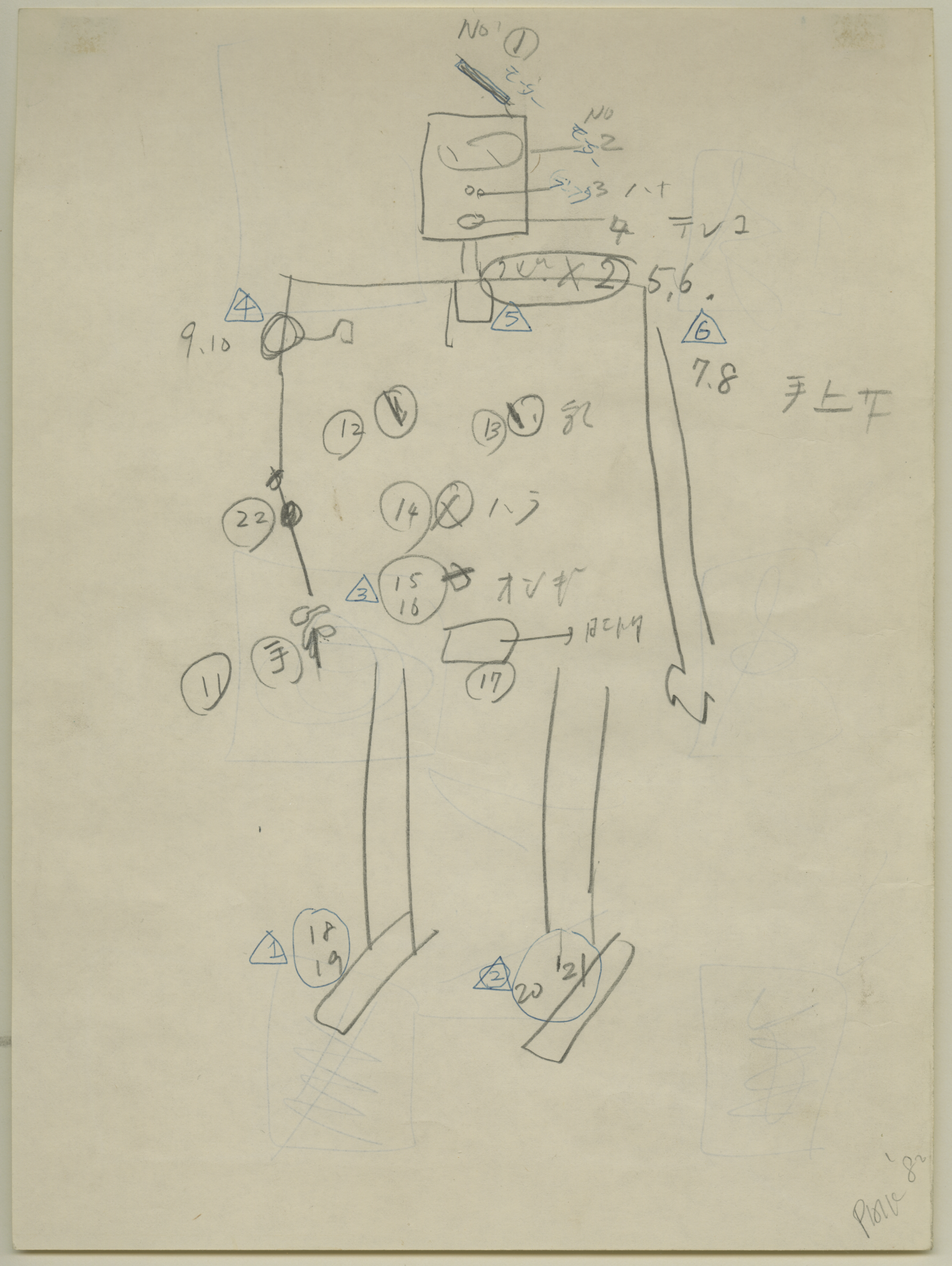

All of this came into play during the Whitney exhibition, when Paik decided that he wanted to take the robot off its pedestal and out of the museum, where he would stage a public event that would attract television coverage. The robot was made to walk up the sidewalk outside the museum and proceed across Madison Avenue, where a staged accident occurred. The artist Bill Anastasi drove his Honda Civic into the robot, throwing it down onto the crosswalk, an event that was, in fact, covered by the local CBS affiliate. Paik was asked by the television reporter what this all meant. He said he was practicing how to cope with the disaster of technology in the 21st century. He also noted that the robot was 20 years old and had not had its bar mitzvah. Playful and extravagant, this performance concluded with the “body” of the robot being wheeled into the museum and reinstalled in the gallery. The street performance demonstrated that Paik did not see his artworks as inert, completed pieces but as objects that could be refashioned in new forms. In this case, the robot became an emblem of the anxiety we were feeling as technology was becoming a harbinger of cheap labor at the same time as it was insidiously dominating our daily lives.

In one final ironic play with the robot, I fast forward to 1989, when Paik released his single-channel videotape Living With the Living Theater. This is a prime example of Paik’s creative manipulation of the electronic image to construct, in this case, a narrative that looks to the radical form and content of the theatrical avant-garde as it simultaneously reveals the contradictions of art in an advanced capitalist society. The Living Theater came together during the 1960s as a collective of performers under the direction of Julian Beck and his wife, Judith Malina. Brilliant and charismatic, they embodied a vision of an alternative collective utopia that featured freewheeling performance pieces such as the celebrated Paradise Now. They remade the improvised theater pieces into a mobile, transparent, and porous space where their genre-busting improvisatory expressions of sexual liberation, drug-taking, and rock and roll could unfold. Throughout the videotape, Paik plays himself as a subversive interviewer and ironist, asking who in a collective washes the dishes and reflecting on the property in Switzerland where Julian and Judith are videotaped smoking dope over the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin’s grave – a bucolic property which, Paik notes, escalated in value when it was sold as a capitalist utopian investment. The tape also records the funeral of Julian Beck in 1985, showing Judith mourning inside the temple and at the graveside. Following the principles of Paik’s dialectical montage, he brings the taped event of the robot accident into Living With the Living Theater so that the robot’s post-accident removal is connected to the mourners at Julian Beck’s gravesite. Here Paik elides the avant-gardes of a new performative technology embodied in the robot, who was born in the 1960s, with the Living Theater, which was coming to life at the same time as a new theater of possibilities. Two years after Beck’s death, Paik reflected on that loss and the last performance of the robot at the Whitney in this videotape. Robot K-456 and the Living Theater, embodied in Julian Beck and Judith Malina, became one in the video as figures of bygone hopes for the future.

Footnotes

1 . Elizabeth Rottenberg, For the Love of Psychoanalysis. The Play of Chance in Freud and Derrida (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019), p. 35.

2. Karlheinz Stockhausen quoted in Edith Decker-Phillips, Paik Video (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1988), trans. Marie-Genevieve Iselin, Karen Koppensteiner, and George Quasha (Barrytown, NY: Station Hill Arts, 1998), p. 29.

3. Jacques Lacan, Anxiety: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan. Book X, edited by Jacques-Alain Miller, translated by A. R. Price (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2014), p. 77.

4. “Postmusic (1963)” in We Are in Open Circuits: Writings by Nam June Paik, edited by John G. Hanhardt, Gregory Zinman, and Edith Decker-Phillips (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), p. 24.

A portion of this essay was first published in The Lacanian Review No. 11, 'The Art of Singularities'. New Lacanian School, Paris, June 2021.

Images courtesy John G. Hanhardt Archives, MSS.010, CCS Bard Library & Archives, Bard College, Annandale on Hudson, NY.