George Baker

Rabbit Holes (Grammatology)

I enjoy “social media” most when I am writing—not sharing something personal, exactly, but something usually dear to me, even if ultimately “useless.” Not an essay, maybe part of a project, hardly systematic, these “posts” are beholden to no art historical standards of scholarship or research. Most often, I call these short reflections rabbit holes; they give me an outlet for all the interests that arise and then fade away, that spark something that may come to fruition later, as something else, but right now needs to be followed to its limits. Digging down deep. For a text that lives for a few people and for a few moments. It is as close as my writing self gets to my teaching self. Thinking out loud. Always digging.

Gordon Parks, Woman who says she is 104 years old, 1943.

This is a photo I came to through the FSA photography resource that is “Photogrammar,” a Yale website. The archive shows that Parks was in Daytona Beach in the early winter months of 1943, mostly taking photographs, hundreds of photographs, of Bethune Cookman College. He took this photo on a clear day in February. A moment later or just before, he would photograph a 3-year-old boy of piercing but worried gaze, his brow knit at whatever he is facing—not the photographer, he looks beyond, on the same oblique as the old woman—looking at history perhaps, or toward history rather. It was the Second World War, it was and is America and he is just three years old in his tight wool cap and his oversized coat with its military patch, just three years old and African American. His face is a weather vane. Other photographs, on the same porch, always with the wood post for comparison: A young woman resting her face in her hand, looking stage left as everyone did that day; an old man, in two coats and a sweater and a bowler hat, his ears akimbo, reminding me in almost all ways of the forensic look of Richard Avedon’s portrait “William Casby, Born a Slave,” 1963, that Roland Barthes included in his book Camera Lucida (“the essence of slavery is here laid bare: the mask is the meaning, insofar as it is absolutely pure…”). The old woman and the old man would sit together on the porch, another portrait, her always in her shades against the Florida light, a 7-Up sign behind them in the shadows. Her sunglasses seem to reflect Parks himself. It is the photographer’s version of the Arnolfini Wedding Portrait. And while I don’t think the single portrait of the old woman is one of Parks’ well-known photographs—I came across it by accident—it seems to want to be emblematic, like his images of Ella Watson in Washington, D.C., as his FSA work began.

The old woman would have been, like Casby in Avedon’s portrait, a living connection to the 19th century, to the Civil War; she would have been born under slavery. But she is all lifted up by Parks’ camera, her head tilted upward, the sun no bother. The store and its 7-Up sign cooperate, like the RC Cola sign in the photo of her male companion—Royal Crown, underlining a reading of his beautiful if well-worn bowler hat—and the wooden post makes of her a heroic monument. She is shadow and she is light, framed by her jacket’s dark fur trim and the black of the contact sheet, encircled by a sunhat of one hundred individual halos, casting lines of sunlight on her face, echoing and displacing her wrinkled skin. In her sunglasses again you see Parks, maybe, perhaps. He seems really well-dressed, in his Sunday finest, in a suit jacket at least, the future director of Shaft. You see the world reflected, in the reflection of this photograph of an African American of extraordinary age. And you do the math, seeing that her claim to be 104 in 1943 means she would have been born in 1839, the year of the public announcement of the invention of photography. Like Ella Watson, the woman is Parks’ personification of the genius of photography. She is a photograph—She is photography—like Watson was, photography as Parks imagined it.

Alan Trachtenberg (1932-2020) by Walker Evans, September 15, 1974.

Trachtenberg had a full-blown theory of photography, a response of sorts to Susan Sontag, and he has not been widely enough recognized for this. It involves a theory of photographic relations, a theory of spectatorship, of how a viewer relates to photographic images.

Writing in 1978:

“Photography is a specular activity; its images are speculations in the double sense of visions and propositions, appearances and thoughts. The photograph is an imaged and imagined relation to a real object, and re-places the viewer toward the object now caught up in a net of new relations—the intricate web of imagination. The image imagines its viewer-subject into being, gives him or her a place, a set of borders. The act of the camera is perforce fictive, perforce ideological. The viewer’s work is to grasp the imagined relation to the world as an idea, and to play over it the critical light of his or her own desires, and not to flinch from withdrawing, from denying power to images whose ideas debase and deform. Criticism is the health of photography…From photographers who are also critics (skeptics) in this sense, their own readers and perhaps writers, can spring a truly speculative photography.”

“...stressing the ineluctable flatness of the surface...”

—Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting.”

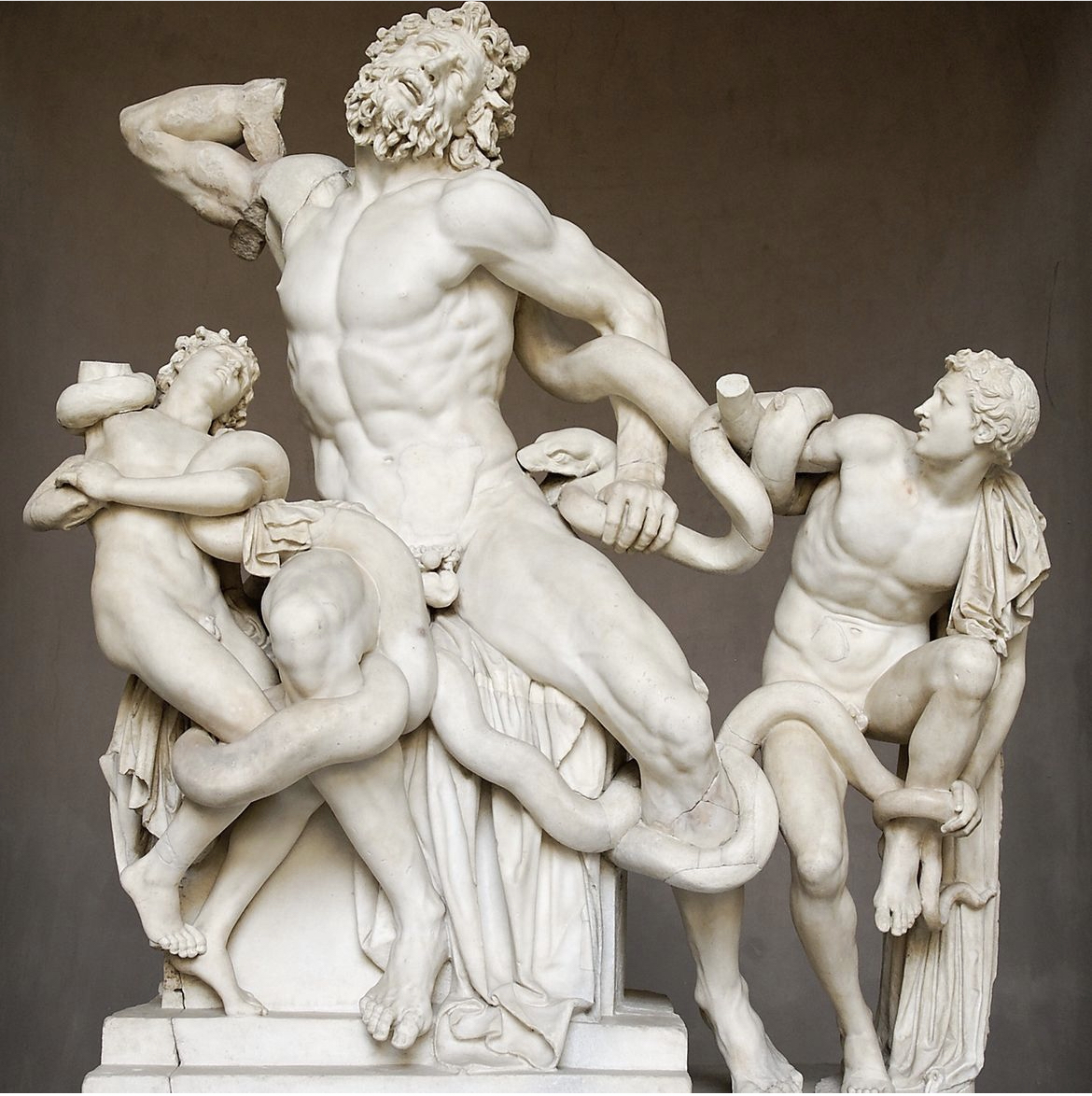

I go down the rabbit hole of the ineluctable, which means something like the inevitable, which has roots in wrestling, in the Latin “locator” or “luctari,” to wrestle. In-eluctabilis, unable to struggle clear of, to escape or to avoid. The word “lucha” or the figure of the “luchador” remembers the roots more clearly, and so I am thinking of Greenberg and Mexican wrestling, towards a Newer Laocoon, another arena in which to act, all of that. Someone must have written the essay already on Greenberg and luchadores? If you dig for a second, you will find all the essays on Greenberg and Sullivanian Therapy, the pugnacious, polyamorous, and fight-prone “Upper West Side Cult” to which he adhered. Ineluctable. Fate as a headlock.

Adventures in summer reading. Yes, I'm reading Hemingway again, and sit by the pool to finish A Moveable Feast. But I am distracted by the young woman that comes out to sunbathe. No, not that way, she is on her phone of course the whole time, and the entire conversation puts Hemingway to shame. There is talk of her upcoming marine safari to watch the sardine migration off the coast of South Africa, to see the sharks feeding on them; there is talk of her friend on a safari watching the wildebeest migration across the plains; she tells a tale of being hit by a whale fin slapping the ocean water; she asks her friend if she has ever run with the bulls in Pamplona, and says she is going with her military friends, the only woman in the group, to run with them next year.

I finish the Feast, and move on to a novel by Elsa Morante, and the narrator tells a tale of seeing a white “dugong” crawl out of the Mediterranean sea onto his island. I have never heard of dugongs and look them up, losing an hour. But then I remember that I began my day over morning coffee reading of Doggerland, a lost area of Europe hit by a tsunami 8000 years ago, a real “Atlantis.” I ponder the connections, the dugongs and Doggerland, in the style of my friend Joni Spigler (you should know her). I read a specific account of the dugongs, searching for them off the Philippines, and the guide's name in the story searching for the dugong is Dogong. I read:

“Dugongs (Dugong dugon) are distant cousins of elephants—they grow up to three-meters and weigh about 400 kilograms. Also called sea cows, they inhabit shallow waters of the Coral Triangle, wherever seagrass is abundant—hence the bovine reference! They are the fourth member of the order Sirenia, alongside the three manatee species. The Steller’s sea cow was a truly gigantic cousin at 8 meters in length—but the last of them was in 1768. Dugong comes from the Malay word duyung, which means ‘lady of the sea.’”

Who were you? is a rabbit hole I often go down. I spend the day beating the heat with an execrable book, skimming, the book on the Black Dahlia murder and Surrealism. Struck by the wedding photo at the double wedding of Man Ray-Juliet Browner-Max Ernst-Dorothea Tanning hosted by the Arensbergs in Hollywood, taken—the book tells me—by a “protege” of Man Ray named Florence Homolka. I go down the hole, finding the blazing portraits of her taken earlier in the 1930s by Man Ray. Obviously in Paris, not the local LA story I am expecting. And then I quickly realize she was Florence Meyer, before she married the actor Oscar Homolka—Katharine Graham’s older sister, daughter of Agnes Meyer, member of Stieglitz’s circle, friend of Picabia. Her childhood “home” in Westchester was where the massive “lost” Picabia abstractions now at MoMA were found in the 1970s, rolled up in the basement under birdcages and a croquet set. The estate owned now, maybe only for a little while longer, by Donald Trump.

I find a photo of her, appropriately, by Steichen. She wanted to be a dancer. I become intrigued by the many photos I begin to find of her, very young, taken by Brancusi—clearly in his studio. And then later, photos by Homolka, of Brancusi, or of his studio, of his sculptures treated like Man Ray & Co.’s heads in the double wedding portrait. I find notices of an Eastern European auction, held during COVID year 2020, selling off a trove of Brancusi’s love letters to Homolka. They seem to stretch over twenty years. He writes in French, signs his name in code, but always calls her “Darling,” in English. She died suddenly, in 1962, in her home in Bel Air.

Who were you, Florence Meyer Homolka.

Morning rabbit hole. Picabia grew up an only child, as a child, but later he did have a much younger half-sister, who was friends with Duchamp’s sister Suzanne, and shared Duchamp’s other sister’s name: Yvonne. Picabia made a drawing of her when she was about 18 or 19 years old, it was in his “anti-Dada” figurative art show chez Danthon, in 1923, and it was until recently in a private collection in Encino. I don’t know too much about Yvonne yet. She wrote—she made books—she shows up on the Google as a “judge” in a naturist beauty pageant in the 30s in France. I recently added this later book of hers to my library: Histoires de marins et chansons rochelaises. It is filled with stories, songs, and drawings that seem to share a lot of the (Francis) Picabia topoi—dogs, drunken dogs, a monkey, graffiti, kitsch portraits … Who were you Yvonne (Gresse) Picabia?

Rabbit hole du jour. Here is a Man Ray group portrait from around 1930. It often gets wheeled out now to speak to the Surrealist group’s complex position in relation to homosexuality. In her otherwise incredible anthology on women surrealists, Penelope Rosemont points to the photograph as her reason for including the artist Georges Malkine—here in the back, on the left—as one of the queer surrealists, along with René Crevel and Louis Aragon (and Claude Cahun, and Valentine Penrose, and ...). But the photograph proves more complicated than that, more wild, and more in need of history. Robert Desnos is at the center, beautiful Desnos, who eventually died in the concentration camps, of typhoid, just before the camps were liberated (this fact often now gets wheeled out to speak to the Jewish members of the Surrealist circle, but Desnos was not in a concentration camp for being of Jewish descent—more history needed here as well, another rabbit hole to plumb). In the wake of Man Ray's film Starfish, made with Desnos, to one side is the actor from that film, André de la Riviere. To the other side of Desnos is André Lasserre, a Swiss sculptor, animalist and student of Bourdelle, why is he there? I love him for his biography, and his work on a monument to Paul Lafargue, Marx's son-in-law and author of The Right to Laziness. The most underknown of artists from the original Surrealist group is then behind, Georges Malkine, but he is kissing his wife, Yvette Malkine, who wore her hair short and “dressed in masculine guise” in these years.

And so the group portrait of a kind of collective embrace (the grasping hands, the interlocked arms, the gazes) does open onto a queer history, to be plumbed. Yvette Malkine was born Yvette Ledoux, in 1898 in Canada; her father was Urbain Ledoux, a figure more remembered now than his daughter perhaps, an American diplomat who became a peace activist, an early American convert to the Baháʼí faith, a “champion of the outcasts” who also called himself “Mr. Zero.” As in, when asked who he was as he ran bread lines and other resources for the destitute in New York, the impoverished of The Bowery,

“I am nothing, call me Zero.”

Yvette Ledoux shows up as the character “Angela Martin” in John Glassco's memoirs of Montparnasse. She had been a nurse in Europe during WWI, a dancer in the Ziegfield Follies, a part of an artist colony in Woodstock, NY. In 1920s Paris, she was the lover of the British lesbian sculptor “Gwen” Le Gallienne, notable for her nonconformity “even in Montparnasse.” The anti-Hemingway memoirs of the sexually-fluid fellow-Canadian Glassco remember Yvette and Gwen Le Gallienne and a dinner at “Chez Rosalie,” on the rue Compagne Premiere, which is also where Man Ray had his photography studio. In a blog about the food habits of bohemian Paris, I learn that Glassco memorializes the night at Chez Rosalie, as “run by one of Modigliani’s former models and well-known for the being ‘very good and incredibly cheap.’ Glassco is turned on by the amount of food the two girls eat. ‘They worked their way enthusiastically though the entire menu of the prix fixe and I found their healthy girlish appetites stimulated my own. We finished off with a chocolate mousse served in little earthenware pots covered by a circle of silver paper.’ Glassco follows the girls home to enjoy a night of three-way pleasure. The next morning the two girls start eating as soon as they wake. Buttered tartines, anchovy paste, tea and apricot jam: a feast of French and Anglo delights far more gluttonous than the pared-down breakfast Parisian women supposedly allow themselves today. Glassco leaves the apartment and buys himself a French pastry full of yellow custard. He is definitely with the girls on this occasion.” By 1929, the two women would sail for Tahiti, with Georges Malkine, and Yvette and Malkine fell in love on this voyage.

Unbelievably, the boat they sailed on was named “Antinous.” (The famed young lover of the Emperor Hadrian.)

This is the background I know so far to the group portrait by Man Ray. It is not an image of Malkine the gay surrealist, not exactly, but it is also a portrait of another Malkine the gay surrealist. There must be better ways to frame this, the homophobia of surrealism or the queerness of individual surrealists not the issue—rather the fluidity of these categories themselves. The photograph fixes nothing. And then, and then, I lose track of Yvette Ledoux Malkine. Where did she go after the portrait? What did she do? All I know for sure so far is that by the outbreak of WWII, she would leave Malkine to return to New York, to care for her father. Mr. Zero died in 1941. Yvette did not succeed in her efforts to get Malkine to leave Europe too, to join her in New York. Still alone, she died just at the war’s end, of tuberculosis, in November 1945, in the VA hospital that specialized in treating TB, just north of Beacon, in Castle Point, New York.

I will never visit Dia:Beacon again, without thinking of this photograph by Man Ray, of Yvette mistaken for a man, of the nonconformity of hers and many lives, and her demise so close by where I grew up—and never knew of her.

“The living being had no need of eyes because there was nothing outside of him to be seen; nor of ears because there was nothing to be heard; and there was no surrounding atmosphere to be breathed; nor would there have been any use of organs by the help of which he might receive his food or get rid of what he had already digested, since there was nothing which went from him or came into him: for there was nothing beside him. Of design he was created thus; his own waste providing his own food, and all that he did or suffered taking place in and by himself. For the Creator conceived that a being which was self-sufficient would be far more excellent than one which lacked anything; and, as he had no need to take anything or defend himself against any one, the Creator did not think it necessary to bestow upon him hands: nor had he any need of feet, nor of the whole apparatus of walking; but the movement suited to his spherical form which was designed by him, being of all the seven that which is most appropriate to mind and intelligence; and he was made to move in the same manner and on the same spot, within his own limits revolving in a circle. All the other six motions were taken away from him, and he was made not to partake of their deviations. And as this circular movement required no feet, the universe was created without legs and without feet.” ---Plato, Timaeus

All of the short texts here were written on my iPhone, to be posted on Instagram. They are in no specific order, are no longer chronological, and have been edited slightly and lightly for this context. --GB