So Mayer

A Walbrook

Why did you take the name of a lost river?

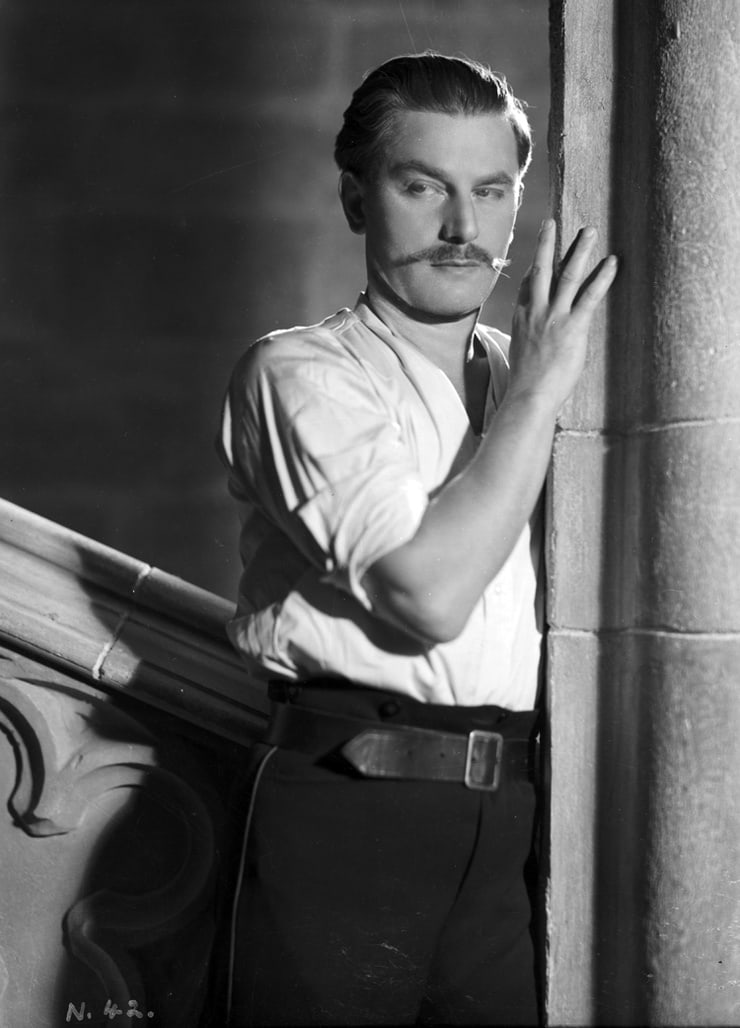

Your name is Adolf so you change it Anton. They say you're a traitor. That it's a mask or a mirror. What they mean is assimilated, what they mean is survivor. The wolf's way, alone. Hackles. What you found in the Hackeschemarkt, in Nollendorfplatz, boys with you in their wallets, cigarette cards, but that was in Berlin. You are in London playing a Prussian officer. A prisoner of war, a romantic hero who gets the girl, no. Gives her up to get the guy. You are in London making a speech about war. Masks and mirrors.

There is talc in your hair, that old ageing trick. They shall know you by your moustache. You are in Canada playing a Mennonite farmer, you who have never even baked bread, let alone grown wheat, the son of a clown and habitué of catch-as-catch-can. It takes all sorts, a shared pot and a big tent. You know how they think of the circus. You tell Max no, your Lolà is all wrong. It's not the glitter and fallibility. It's the work hammering tent pegs, ironing costumes, sewing sequins, sucking off the peep show swells. Whatever brings a pfennig. clowning. Well, that's hiding it, the work, everything easy.

Max, the first Max, in Berlin. He tells you about Pierrot, the great tradition, the great illusion. Dell’Arte, he stresses, a theatre of glances; even its sets like fluttered eyelids, like slanting stares. Max Reinhardt who taught everyone everything. Even Marlene, who was just a convent school girl before he found her. Bitter, bitte: you and she, the circus boy and the cut-glass girl, both playing the demi-mondaines to entertain Americans. You study her in Die Blaue Engel, thinking how you’d play that role. Imagine drawing her a moustache of soft kohl. Did you meet in Hollywood? Unhappy days, she had her circle, all the French emigrés eating lunch cooked with her own fair hands. Mutti Marlene. But you arrive too late and burdened with the wrong name. Not Jewish enough for America. Although you are Jewish enough for Hitler.

Now it's over and here you are in powder, exhorting your old friend to fight, fight by which you and you think the Archers know this means fuck. Although dear Roger doesn't. When you filmed the fencing scene in the bare old parade ground all you could think was the smell of sawdust. Your father in the ring shadow-boxing, collapsible swords, the horses, all the warm muscle of it and this the giant boxes that tower over you and command your performance. Emeric, your ringmaster, is flexing a foil against his foot as he describes to Michael and Roger, yes slash slash, a duel he must have seen in his youth. They are none of them young now although a dab of pancake. You're younger.

You think about your mother's father who took communion, he too was playing a role hoping to survive. It's not like it was invented with Dreyfus, anti-Semitism. Wasn't that the whole point of the trial that it has always been here, a spectre haunting Europe. You would like to play Dreyfus: another Pierrot. You would play him like Maria's Joan all face and fire and refusal. A tribute, as his trial was; a witch hunt. Roger charging in as Zola, shouting J'accuse! You love his big clumsy raffish smile. In the war one, what was it called? A Manner of Life and Death. Manners maketh man, that’s Roger. No, it’s Matter. The Shakespearean melancholy: the good man out yearning on the sidelines, that crash like T.E. Lawrence. What happens to men like us? Roger, you say as he strides over whipping his foil, we should do Dreyfus, but the camera gears are grinding and the lights and – Mark!