Andrew Hibbard

Eggplant, Banana, Super Glue

In my current course of NHS-furnished Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, I have been told to filter out my negative thoughts, to become aware of building a mountain out of a molehill.

I don’t particularly believe in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (in my undergraduate psychoanalysis seminar, I became convinced I was a Lacanian hysteric). CBT feels like a lot of clichés inching toward the worst form of mindfulness. But I increasingly feel like the cliché might be the most important form of knowledge. It’s probably wrong to summon Audre Lorde in this context, but I do believe she is right. “[T]here are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt, of examining what our ideas really mean (feel like) on Sunday morning at 7 AM.” That even holds for the most trite of ideas.

I bring this up because I’ve recently been thinking a lot about my relationship to art. Something that has always plagued me is the necessity to fit into a taxonomicstructure of the art world: artist, collector, critic, curator, dealer. My education in critical theory made me uncomfortable with all of these labels, despite being trained as a curator (or so my degree says). My CBT toolkit would suggest that I should bemore confident, that instead of focusing on how I have failed to fulfill some idea of these taxonomic structures, in some regards, I should focus on my successes, what I have done. I do curate and write things sometimes, ergo, those are my places in the taxonomy.

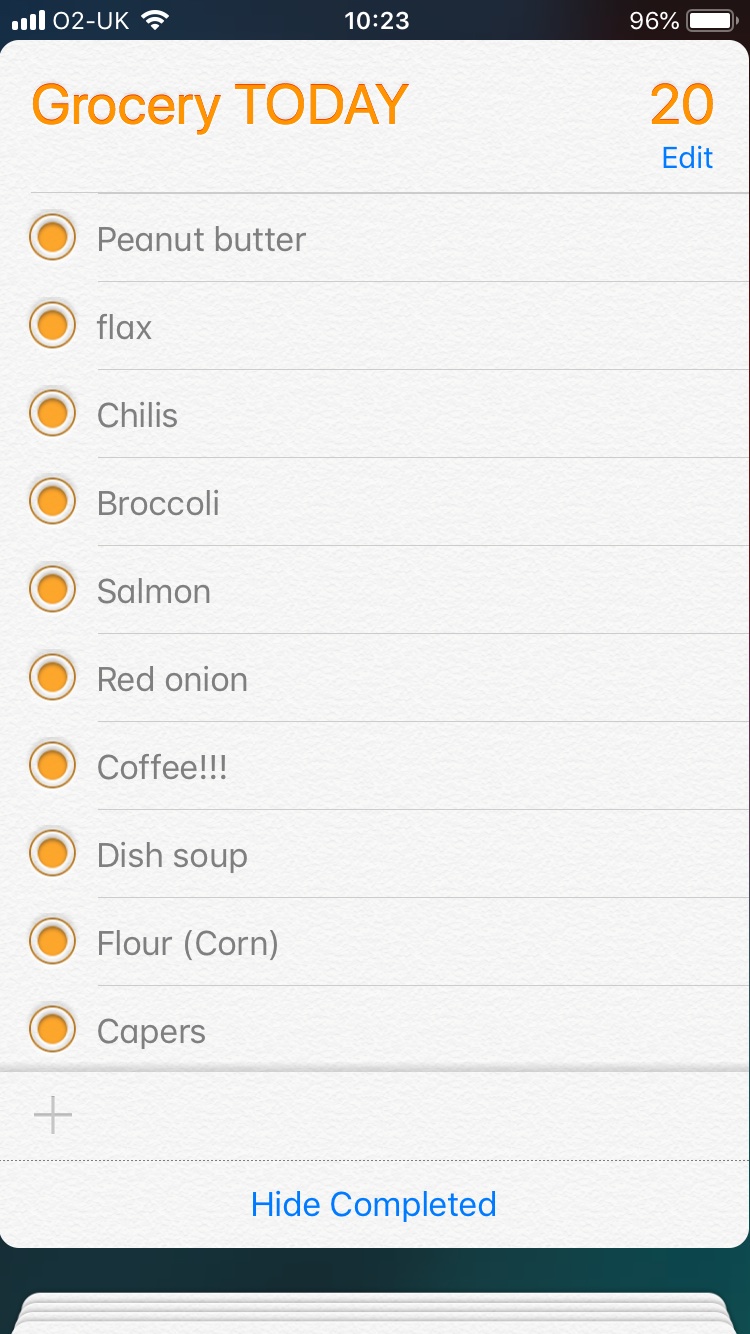

This presents the problem to me of what to contribute to this context. What have I written that hasn’t made it’s way into the world. Or photographed? I take a lot of pictures of dogs, but those always make it out into the world somehow. But in fact, so much of the writing I do, we all do, is enclosed to Post It notes and emails and other private channels. This is the way I am most a writer. And the thing I write about most is food. I’m constantly worried about what to eat. My dear friend Janique loves to ask me “what are you having for dinner?” “What should I make for lunch?” As we like to say, this is a question of great intimacy.

My interest in food might come across as some millennial cliché, but I do see that food has been an indelible aspect of my identity and cultural expression. My grandmother immigrated to the Boston area from Newfoundland in the 1940s, and my aunts and uncle would always tell me how they had to schlep to Wilson Farms to get the produce and dairy and meats. As my mom would say, “we were poor” [more accurately, upwardly mobile lower middle class] “but we always ate well.” My grandmother believed that preservatives were going to be the death of America. She was probably right.

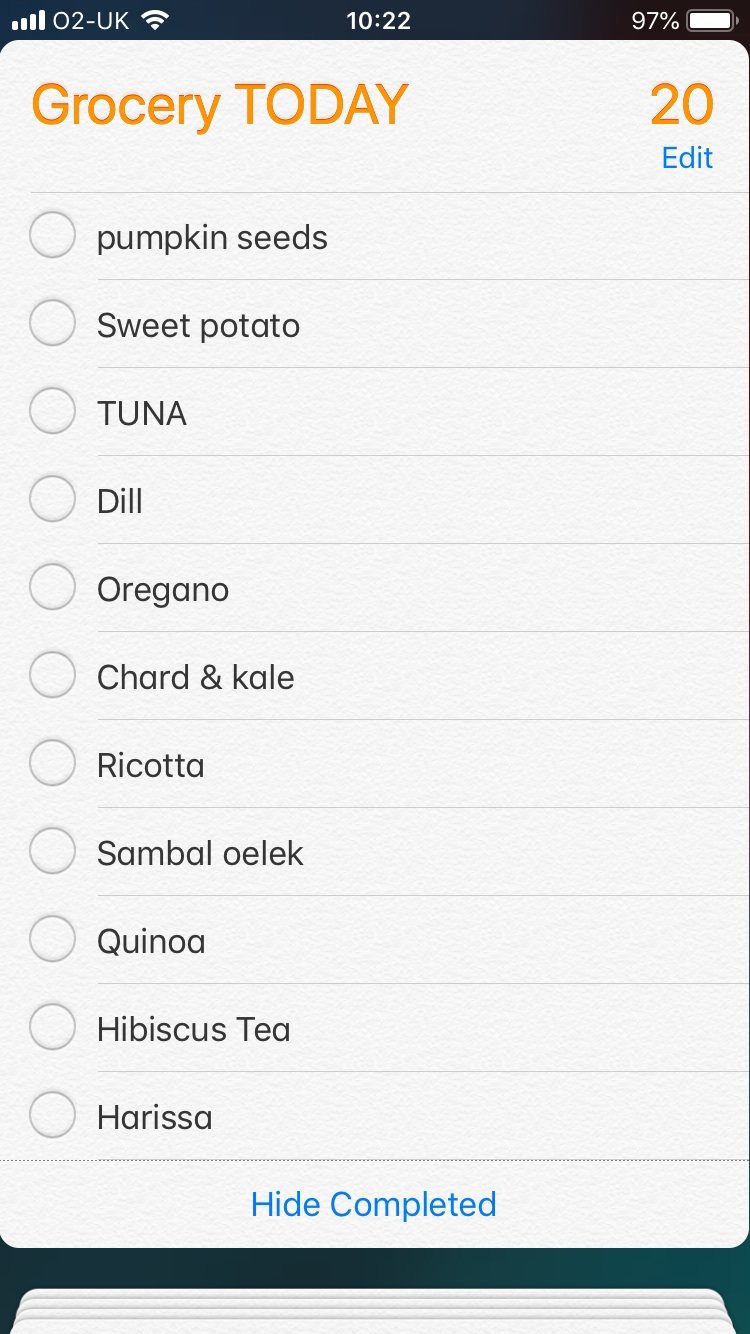

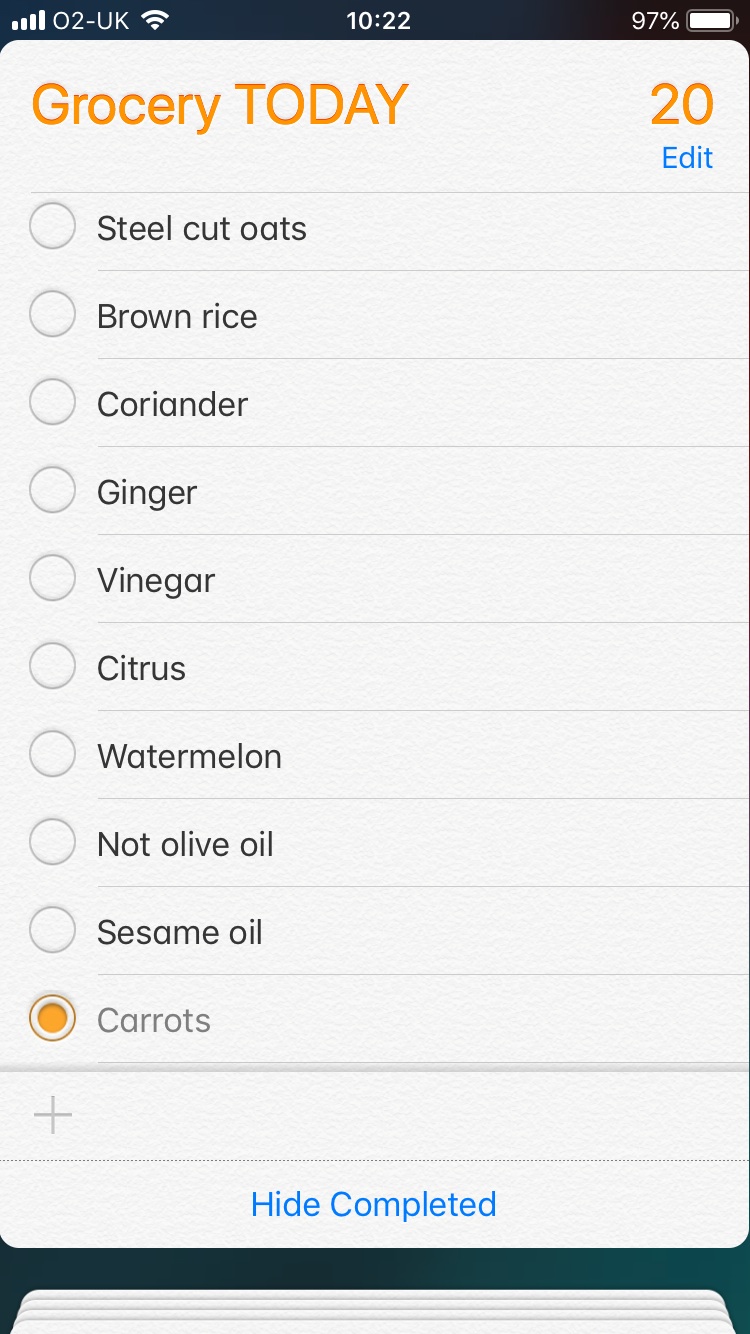

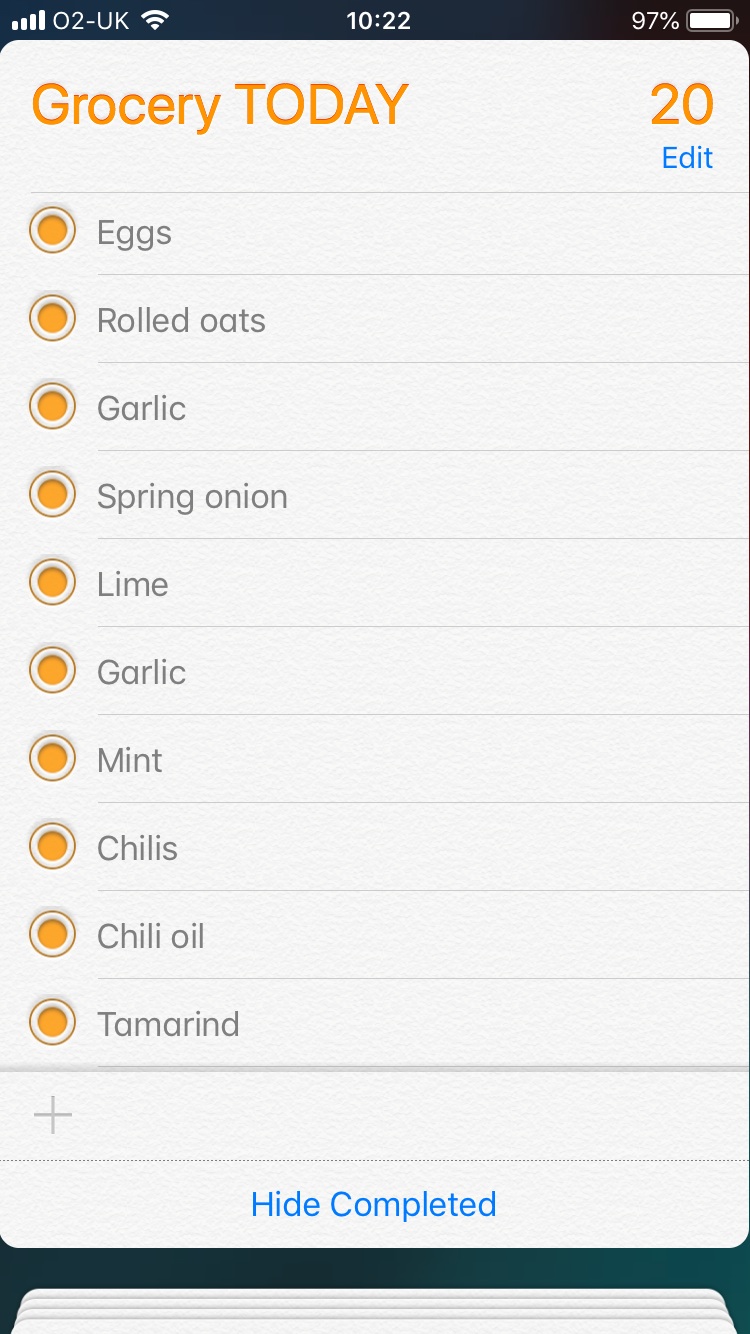

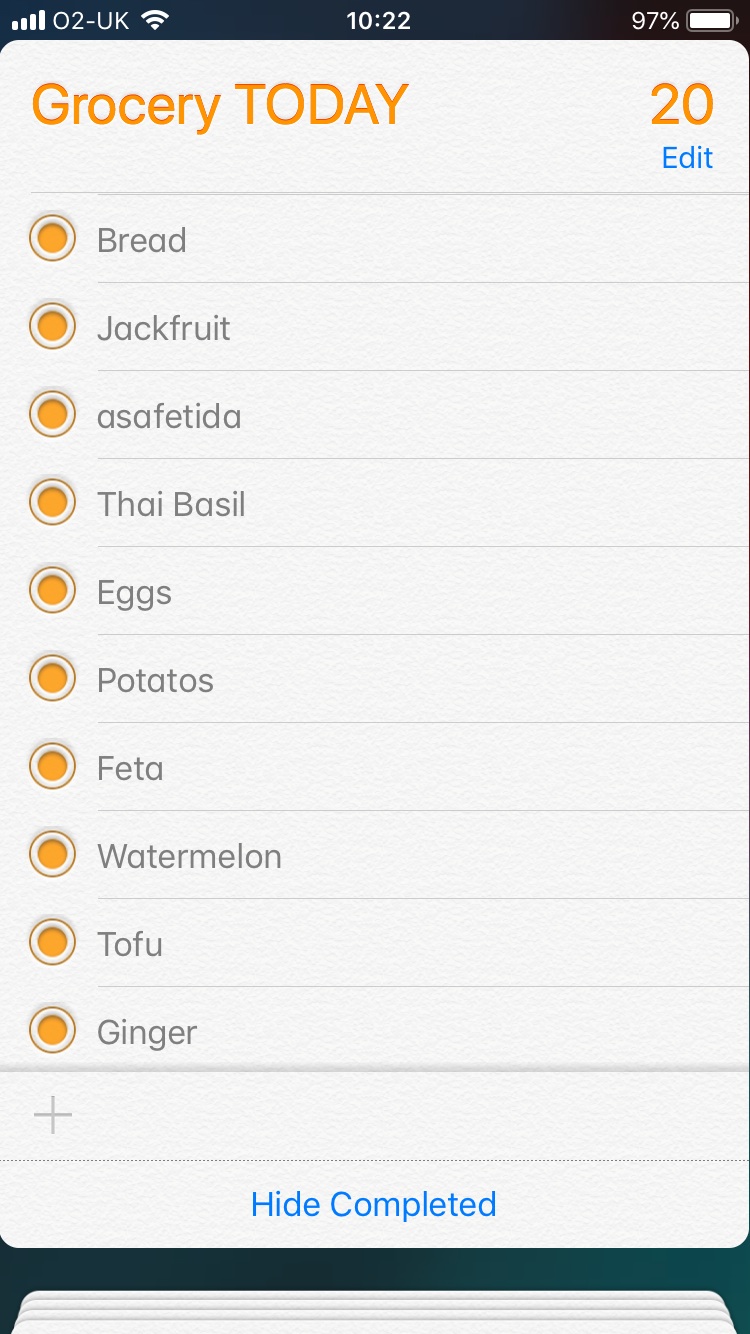

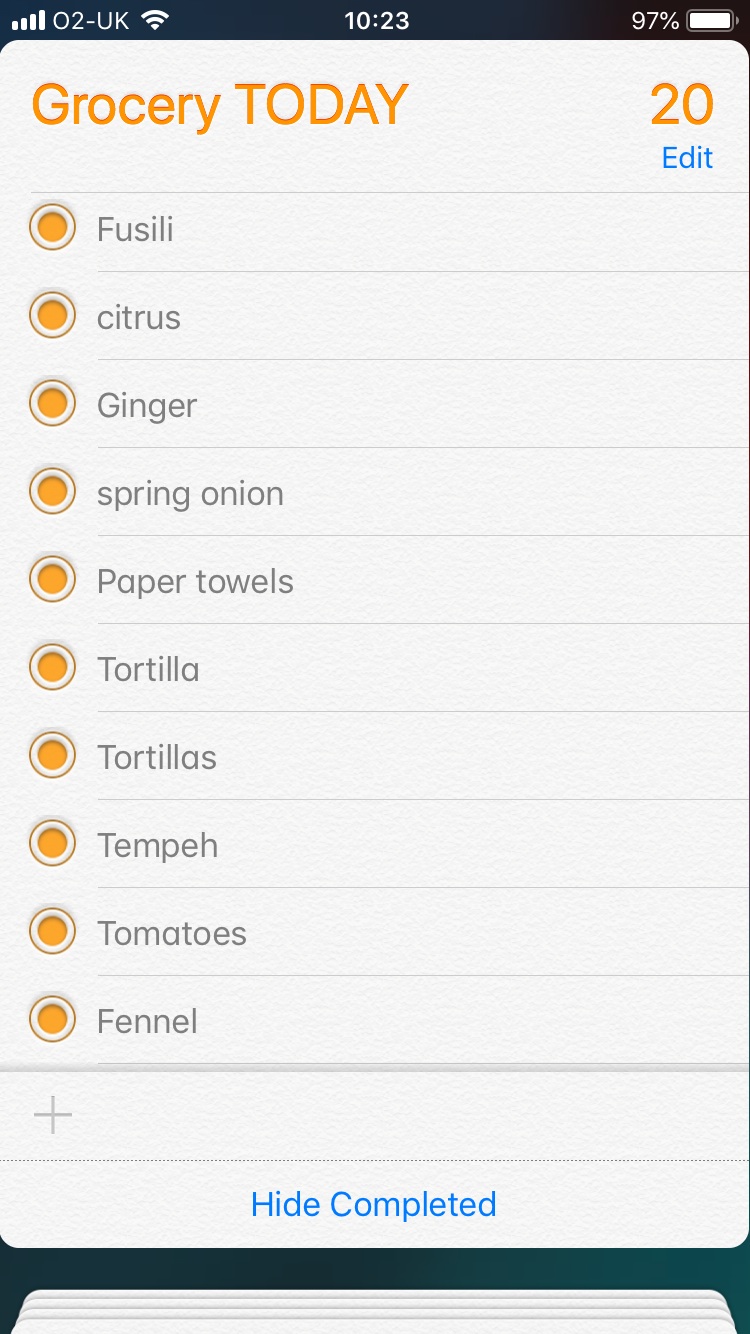

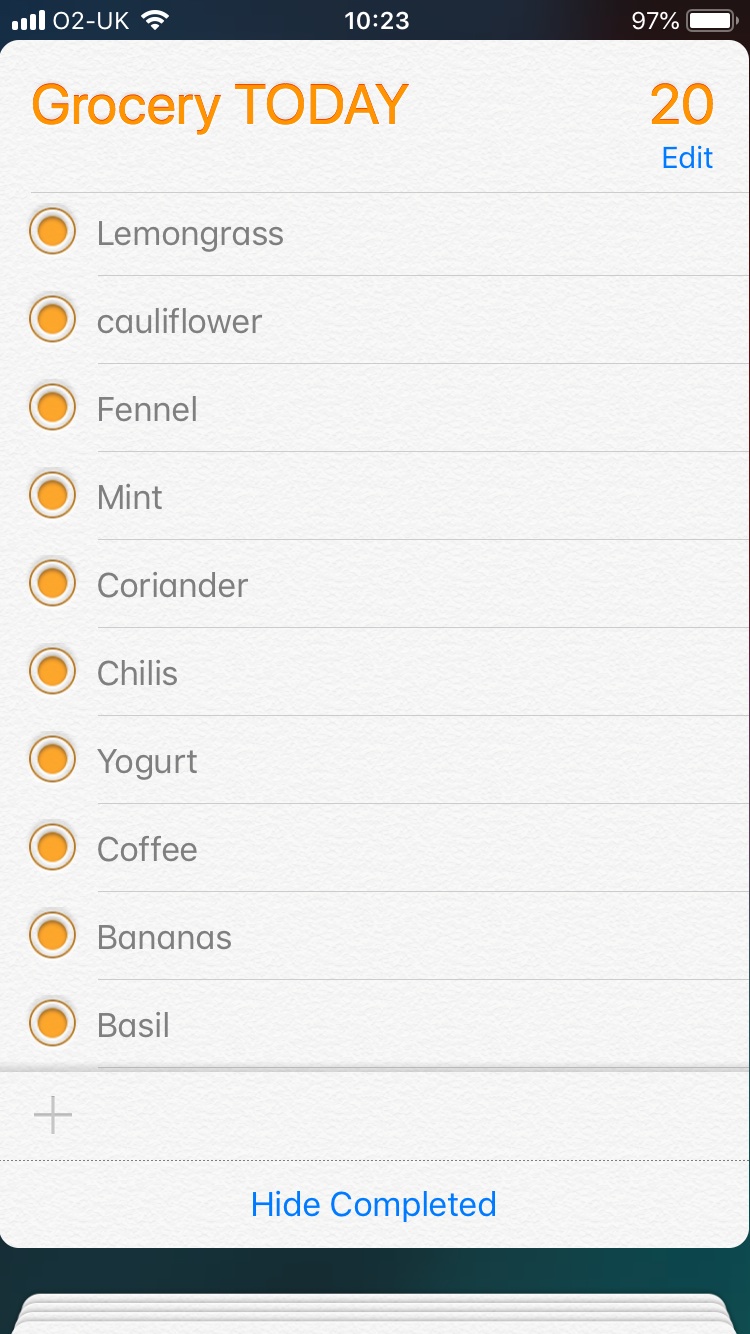

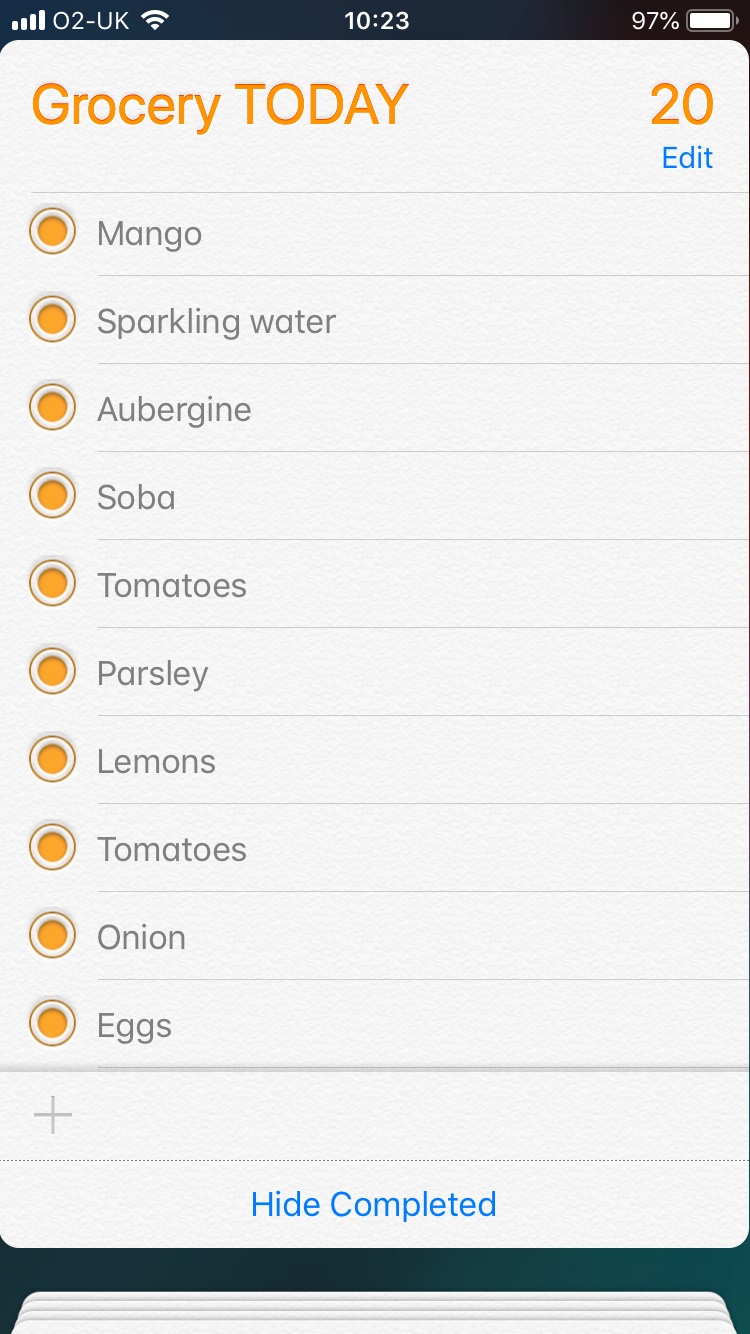

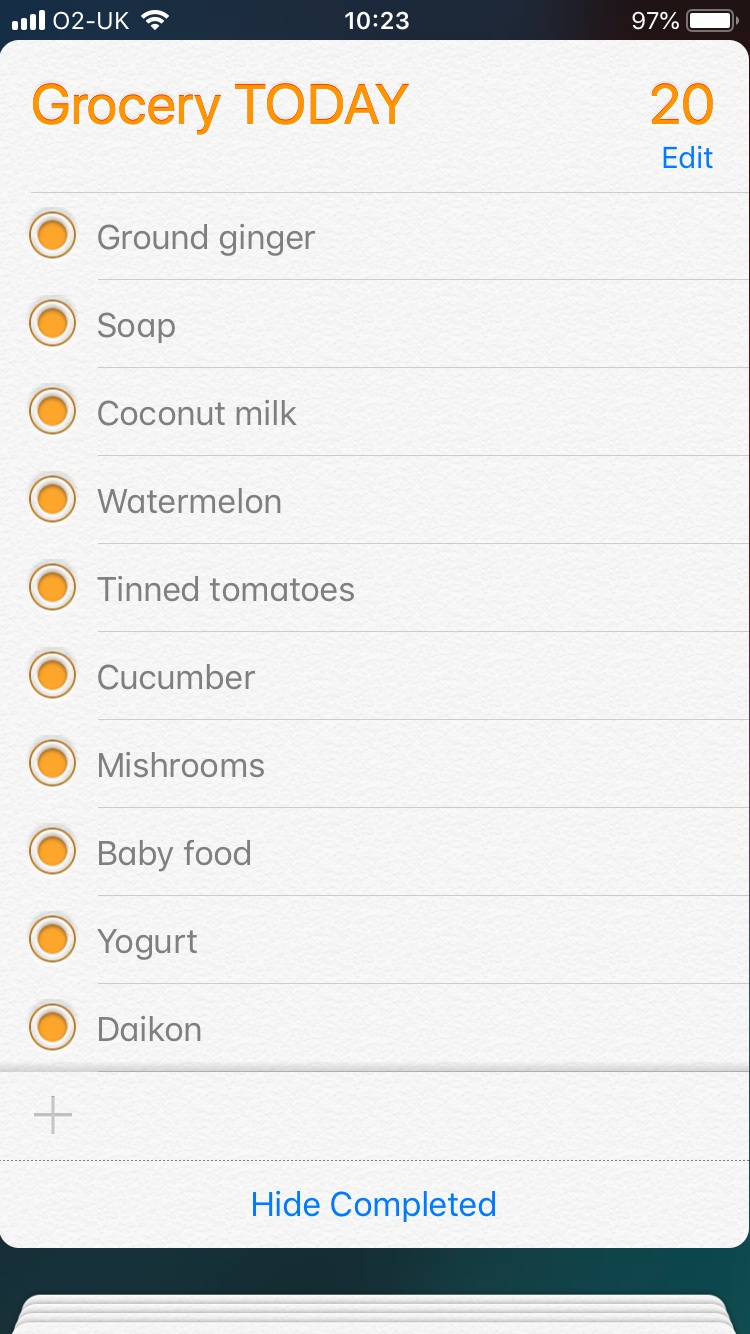

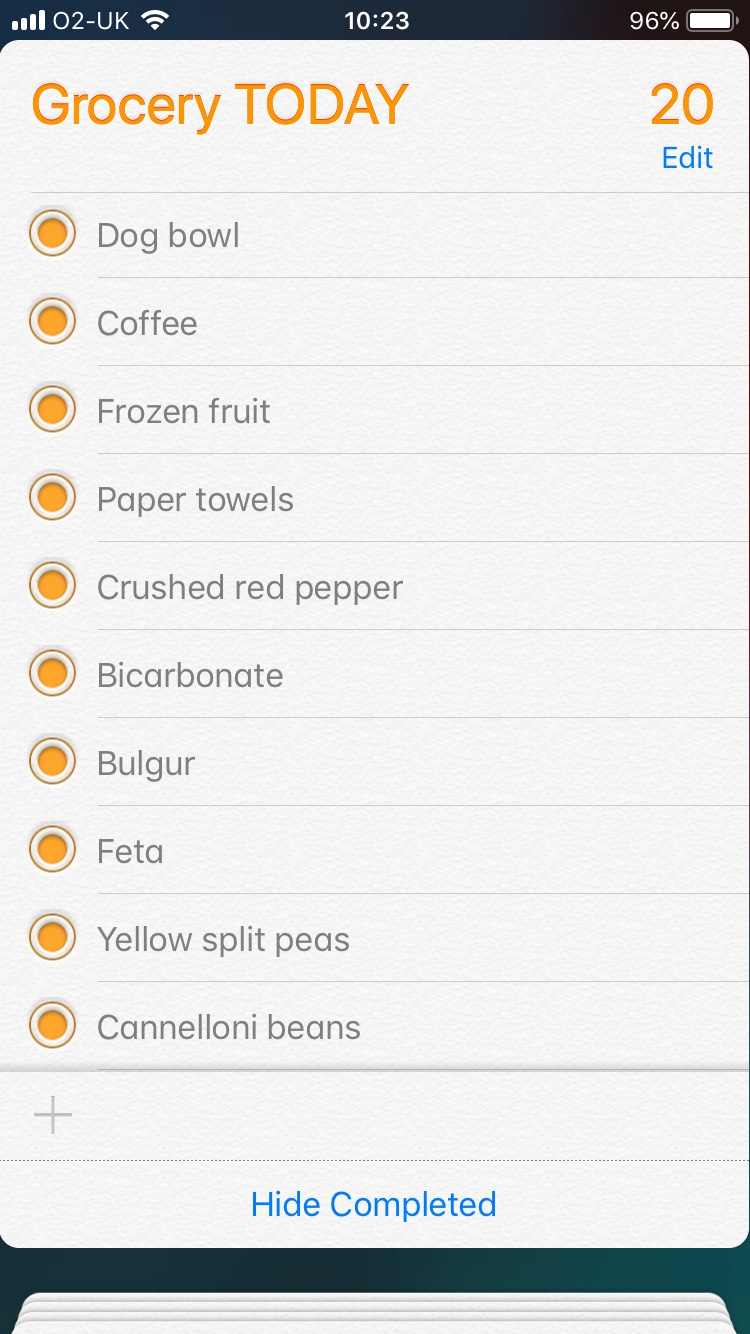

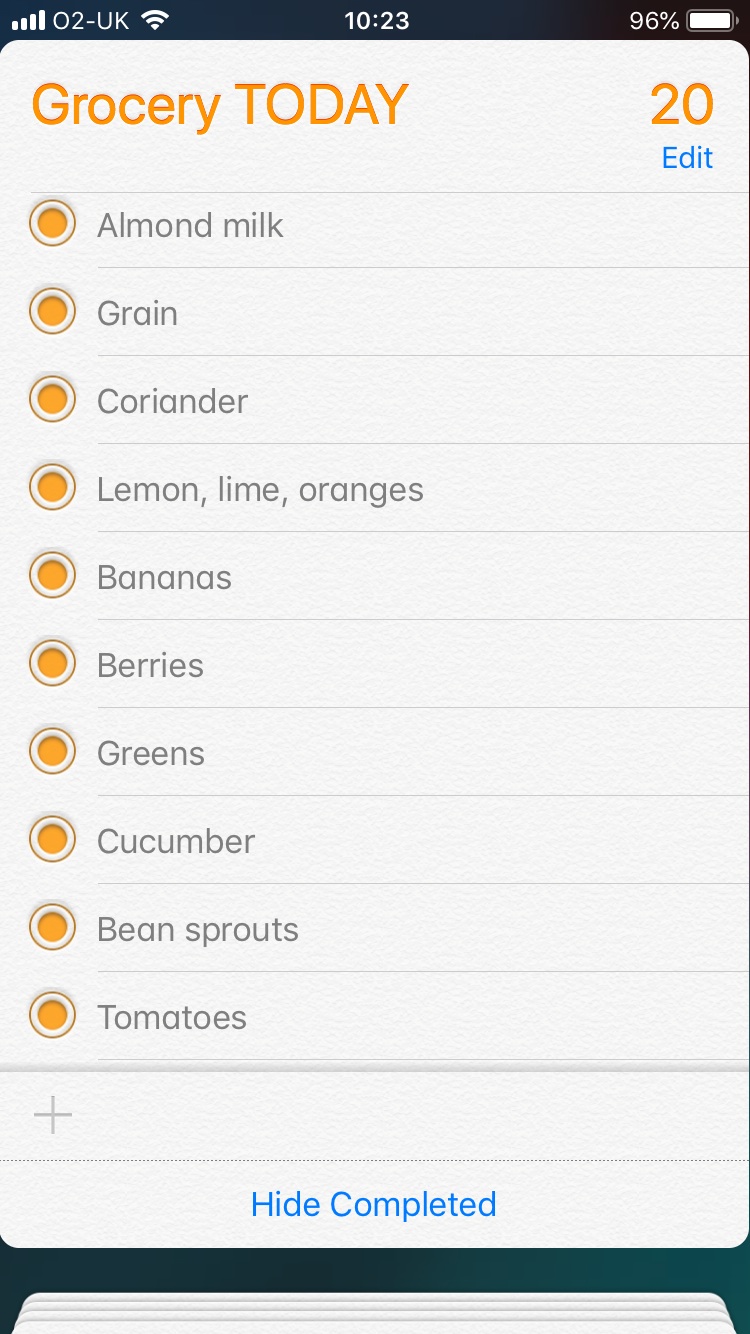

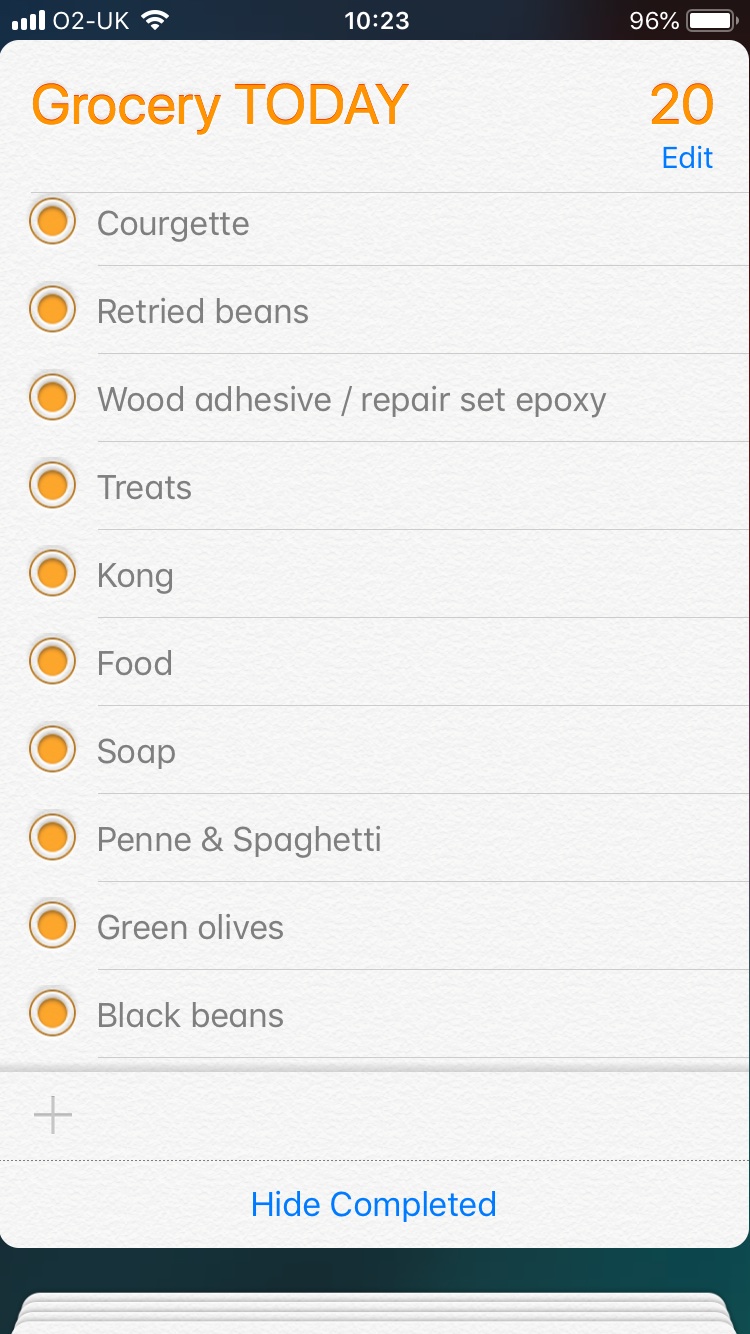

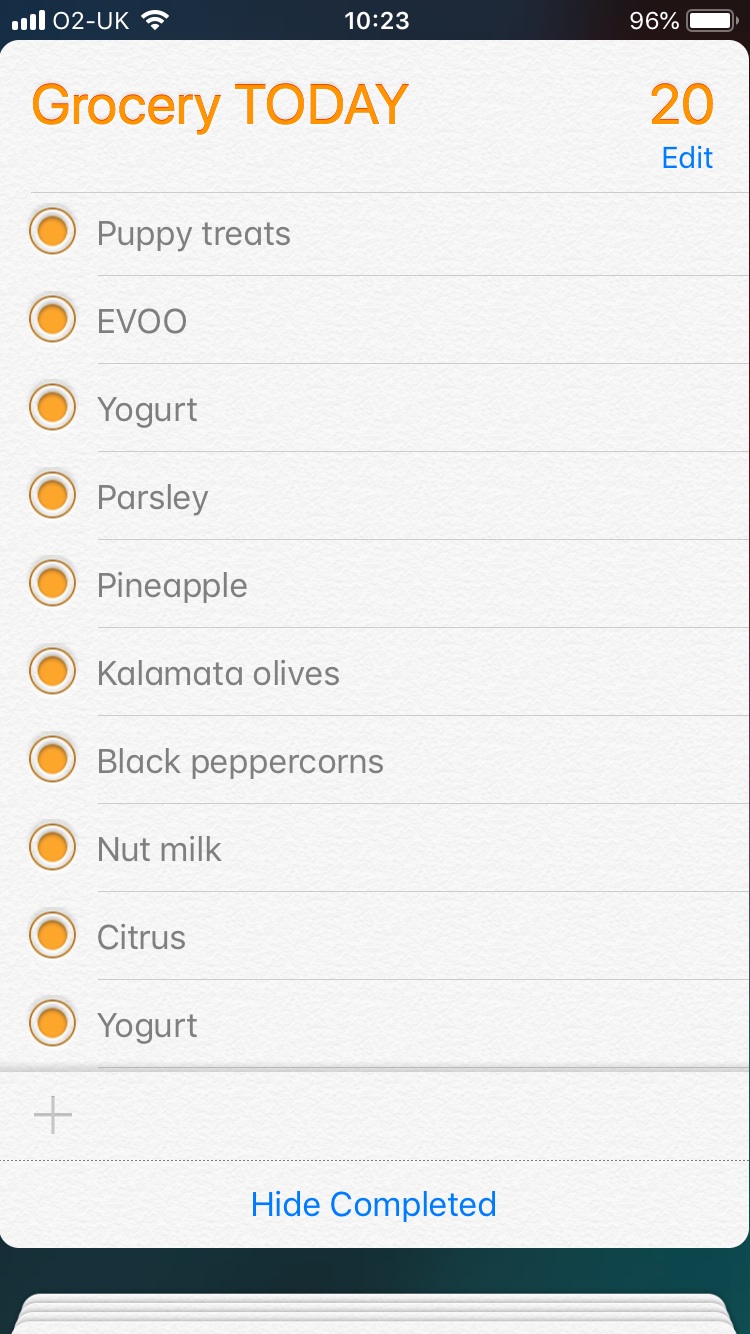

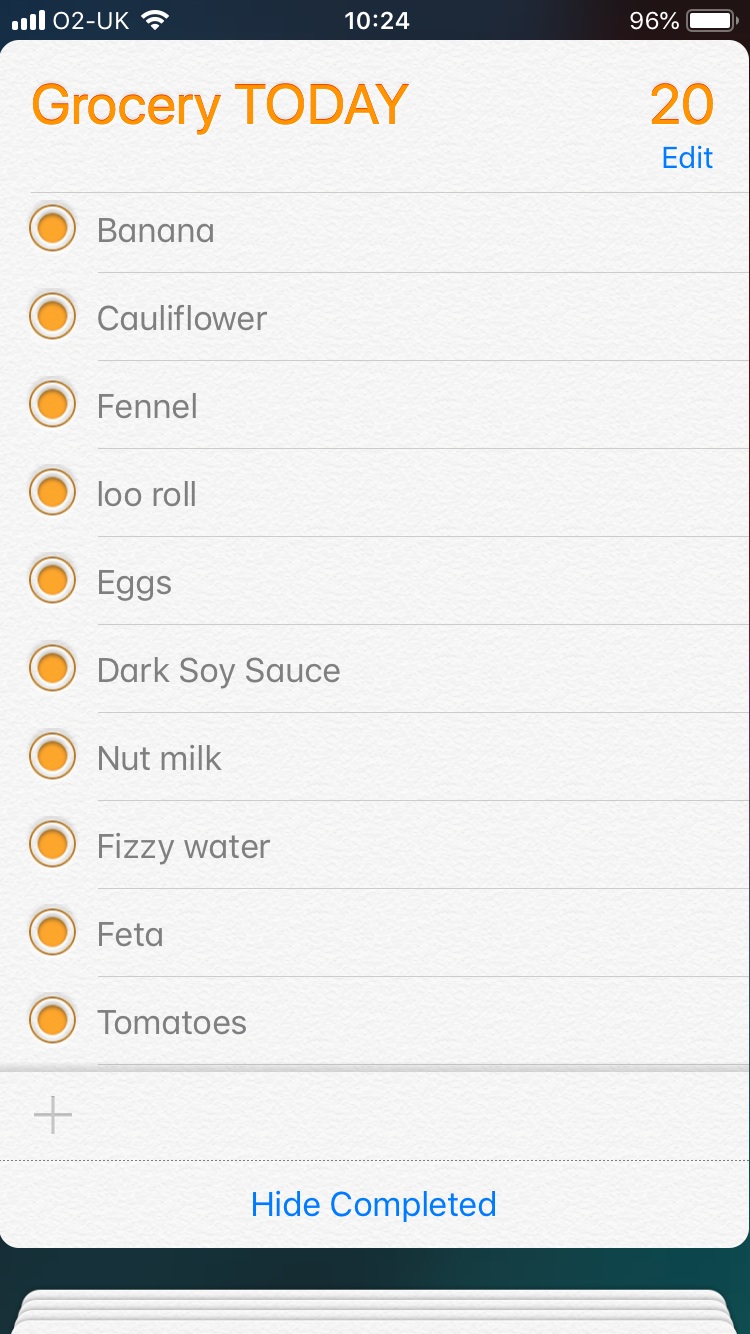

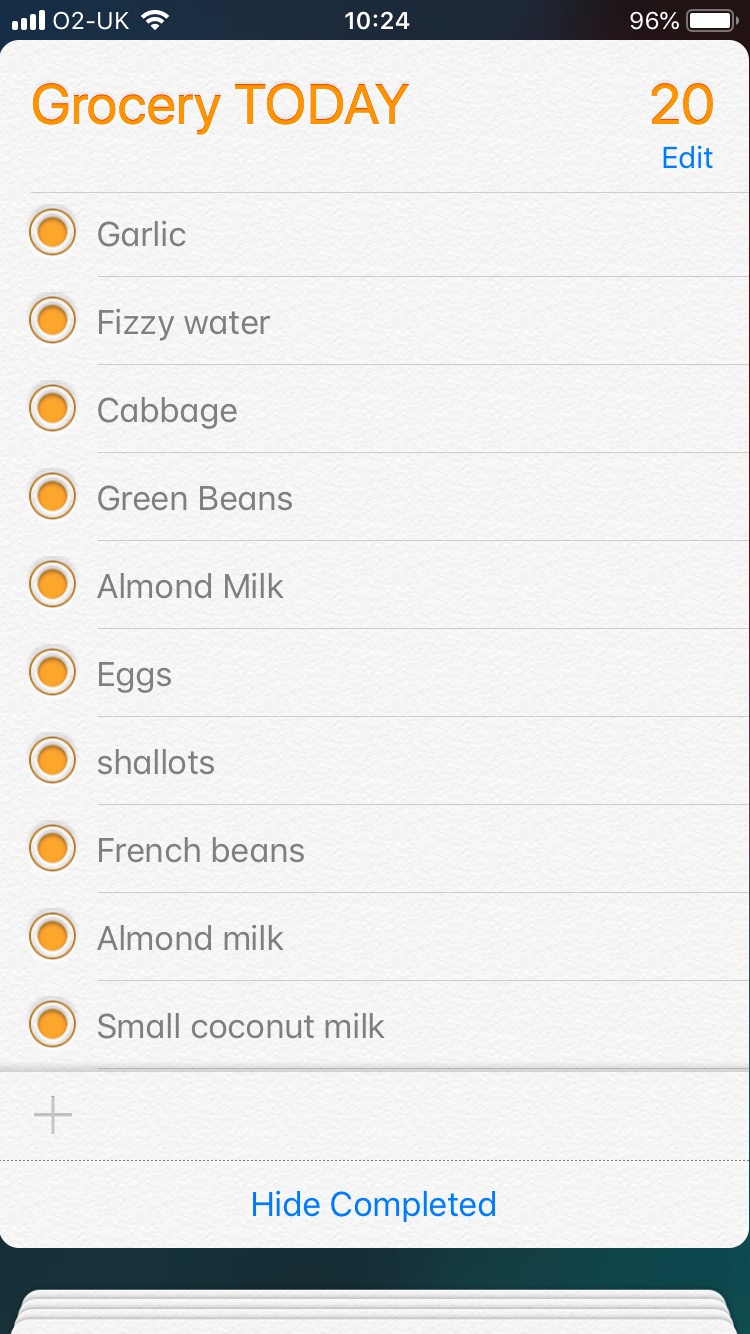

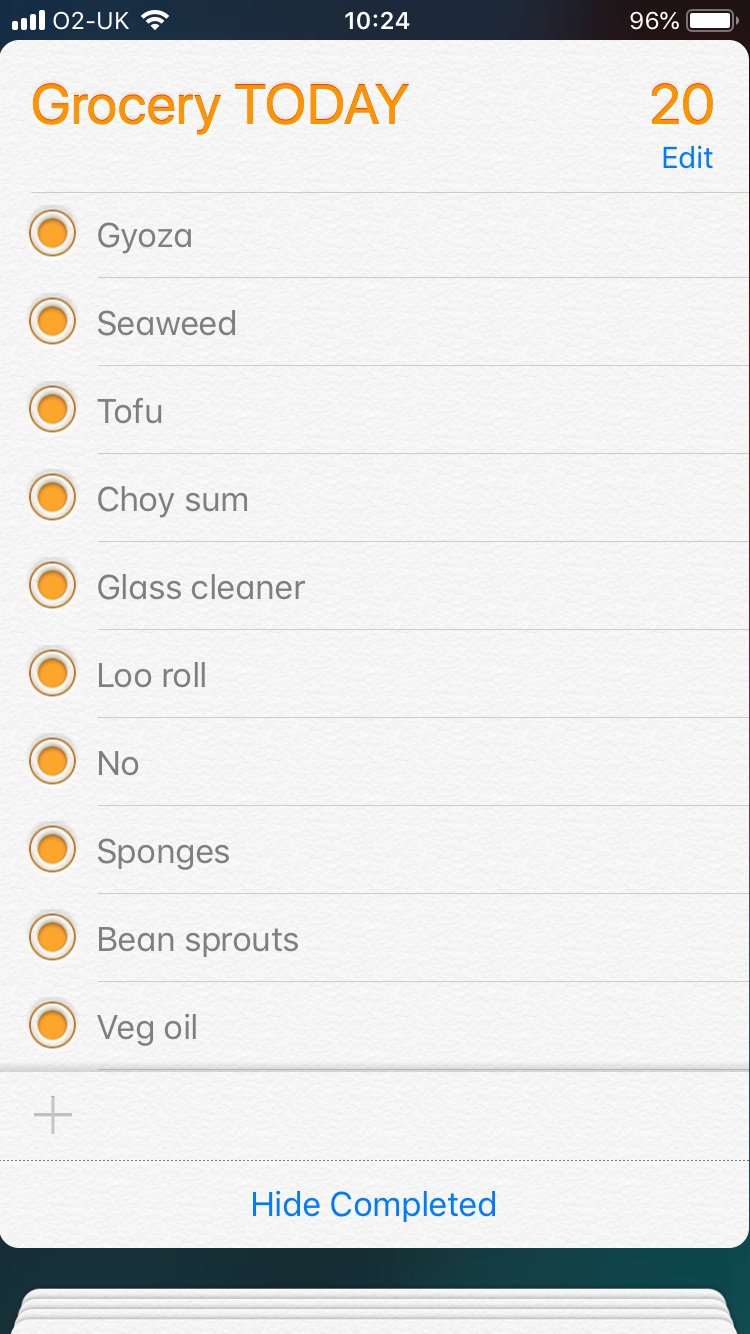

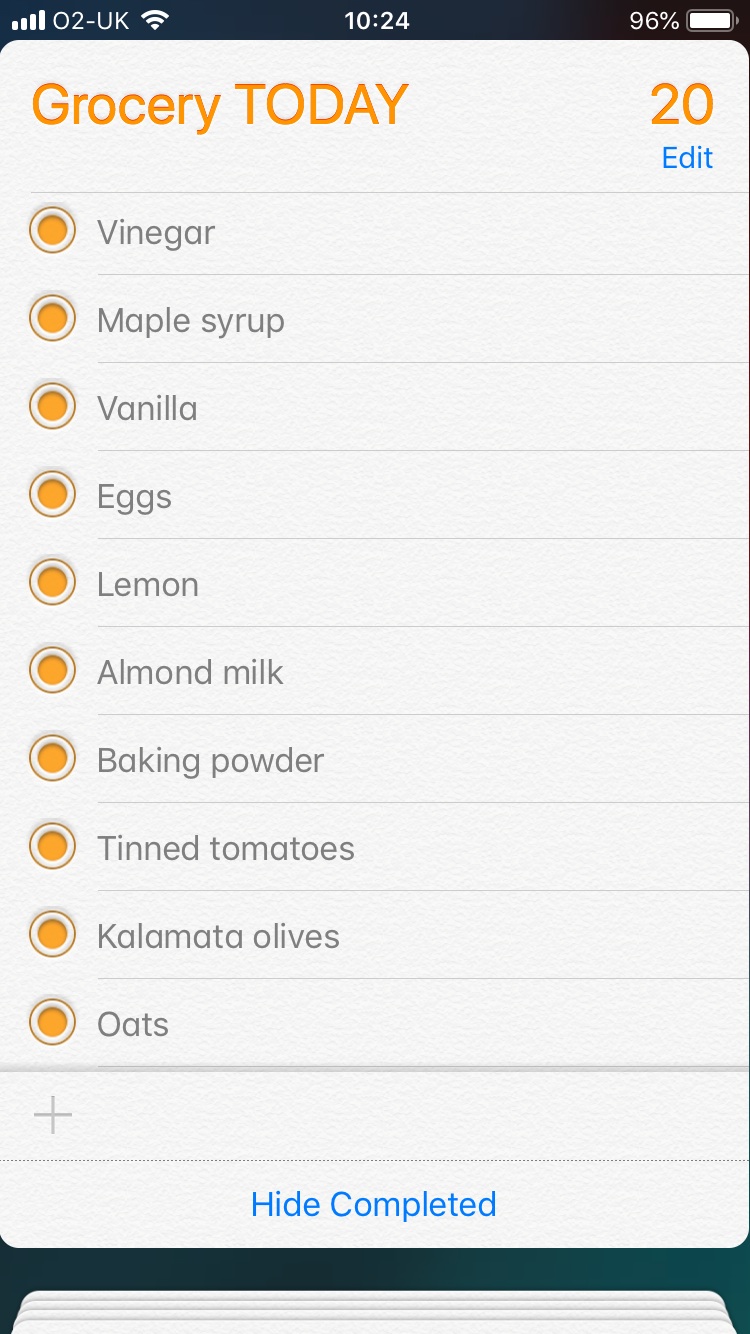

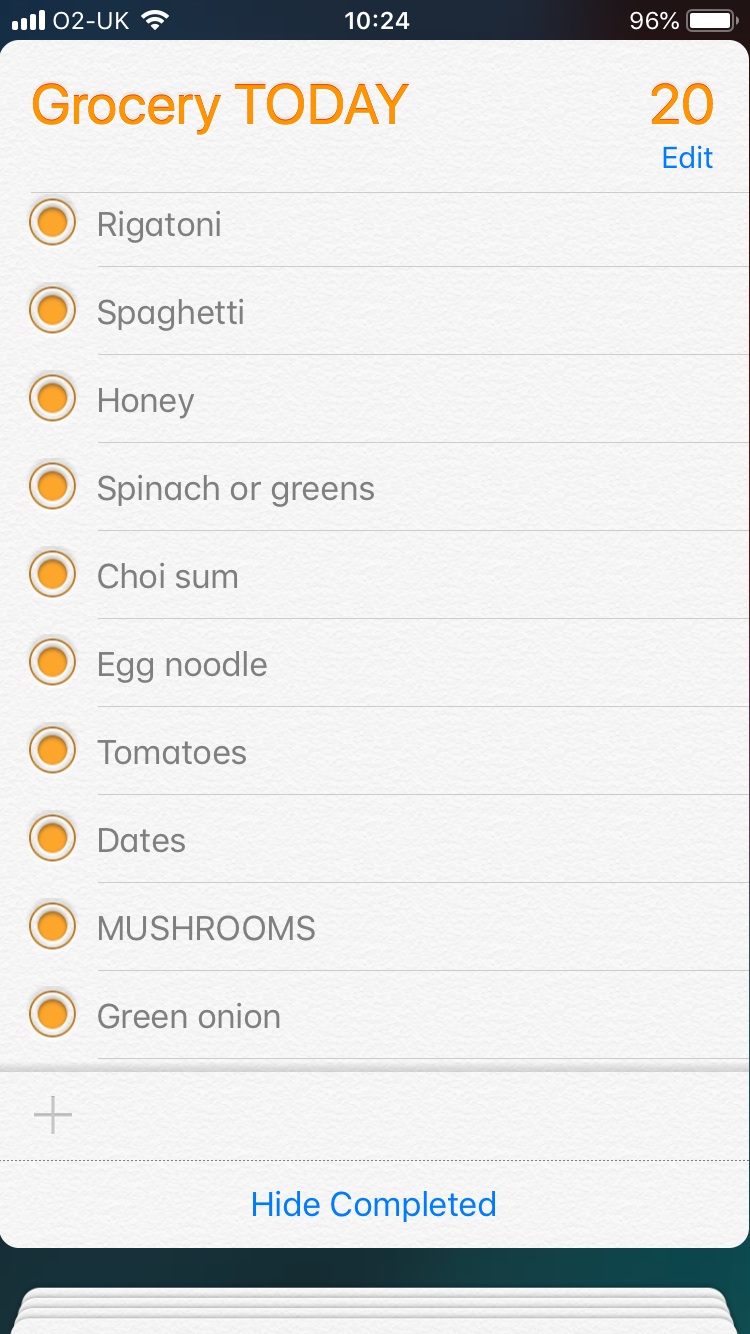

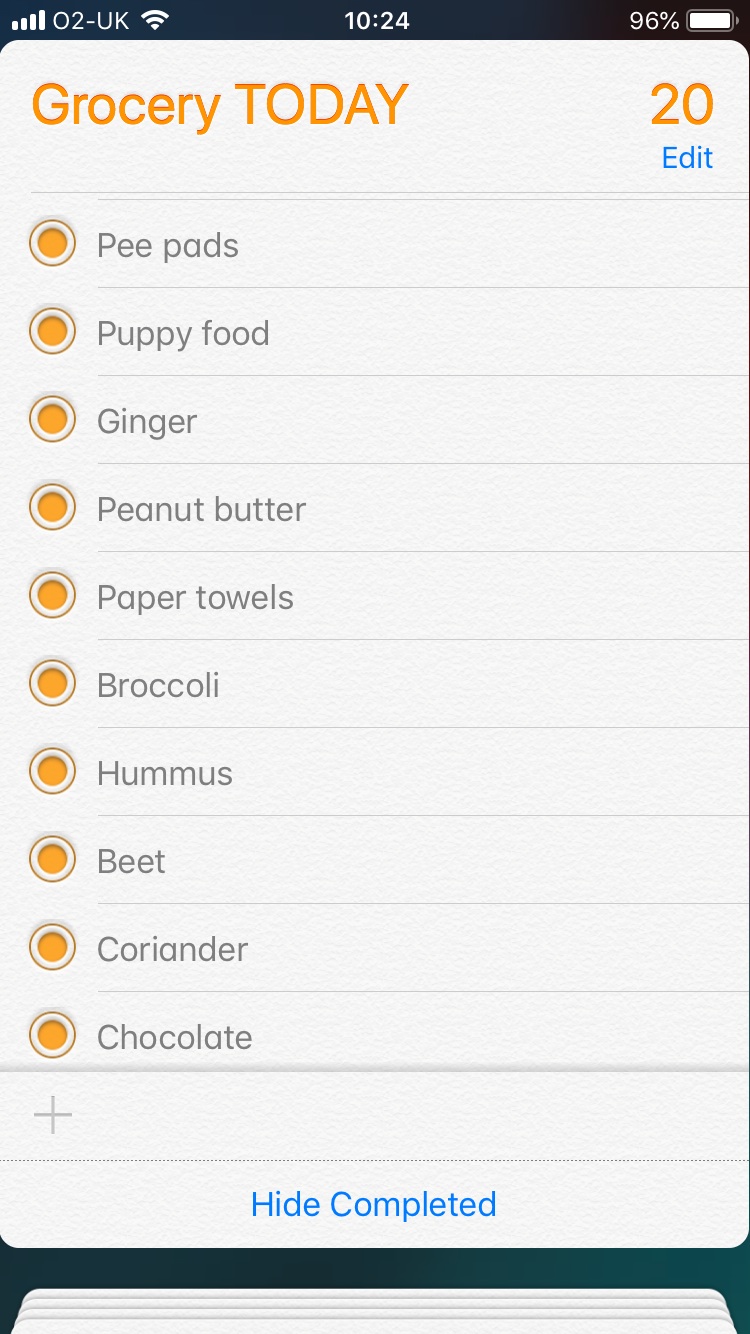

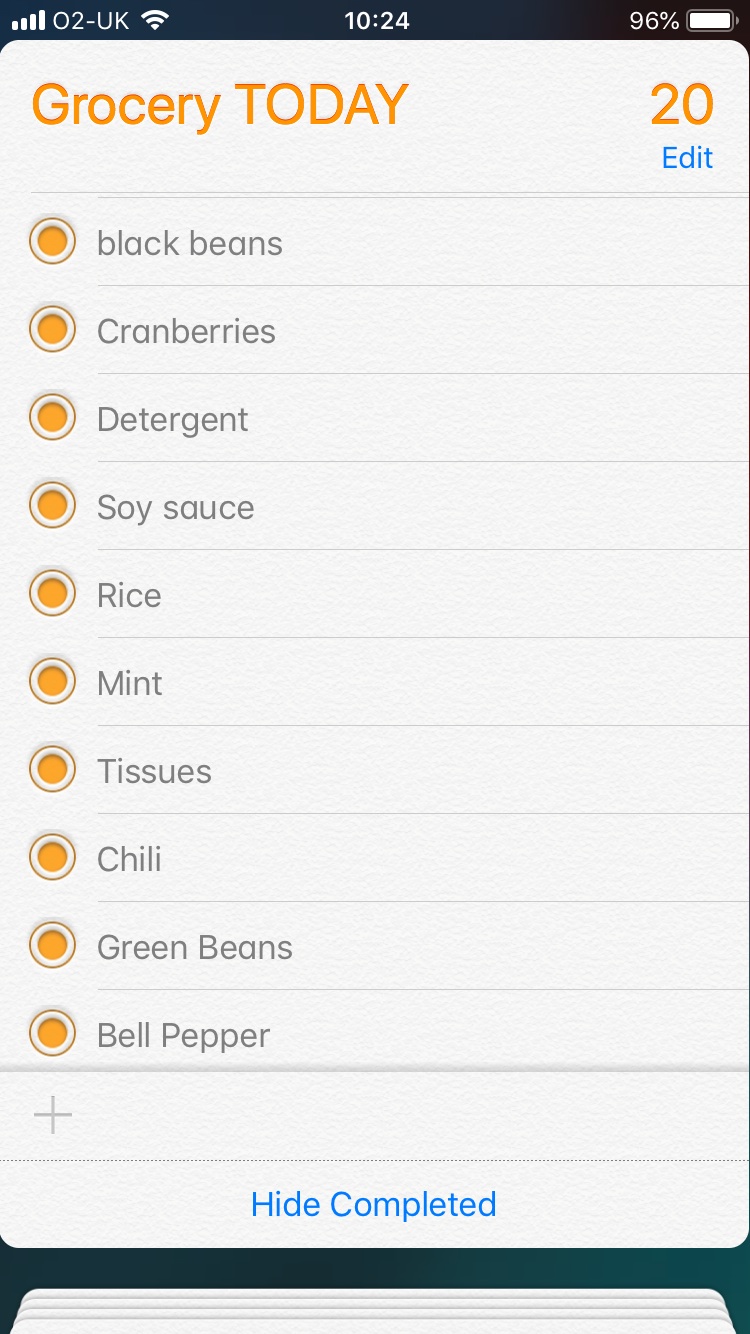

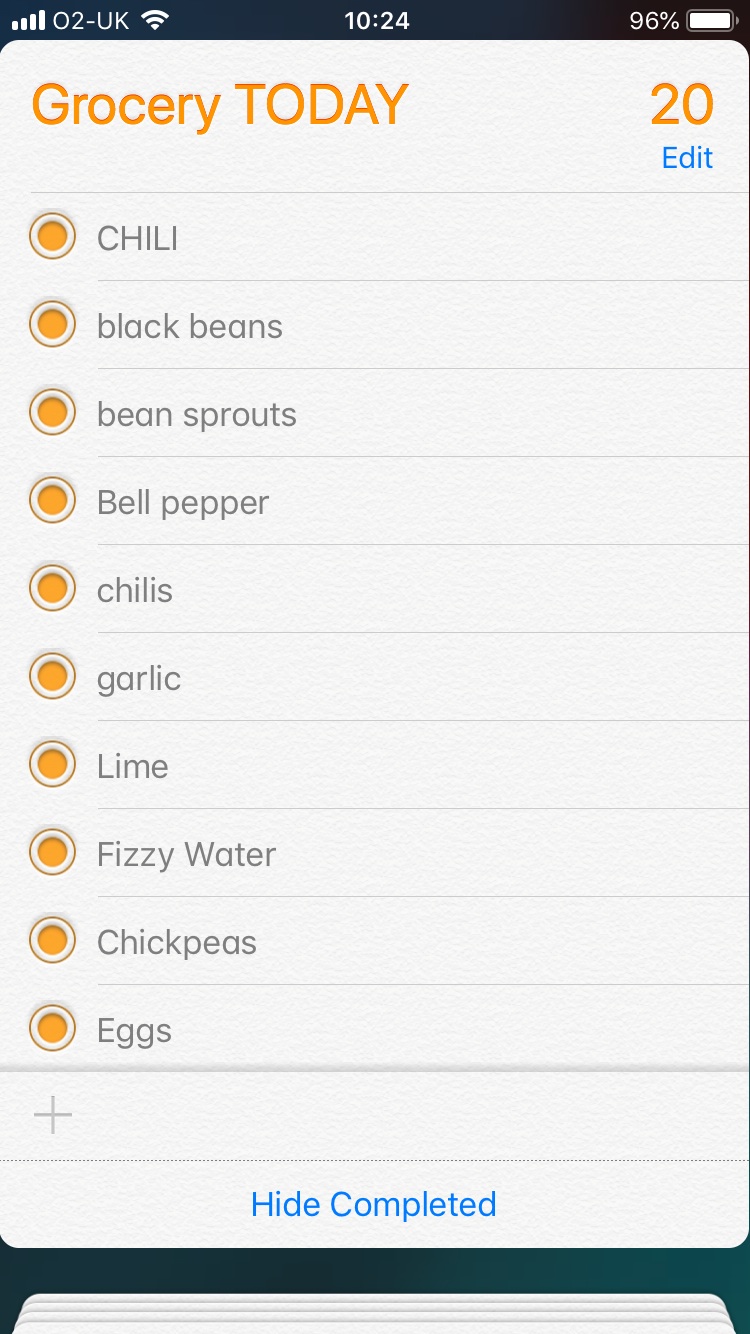

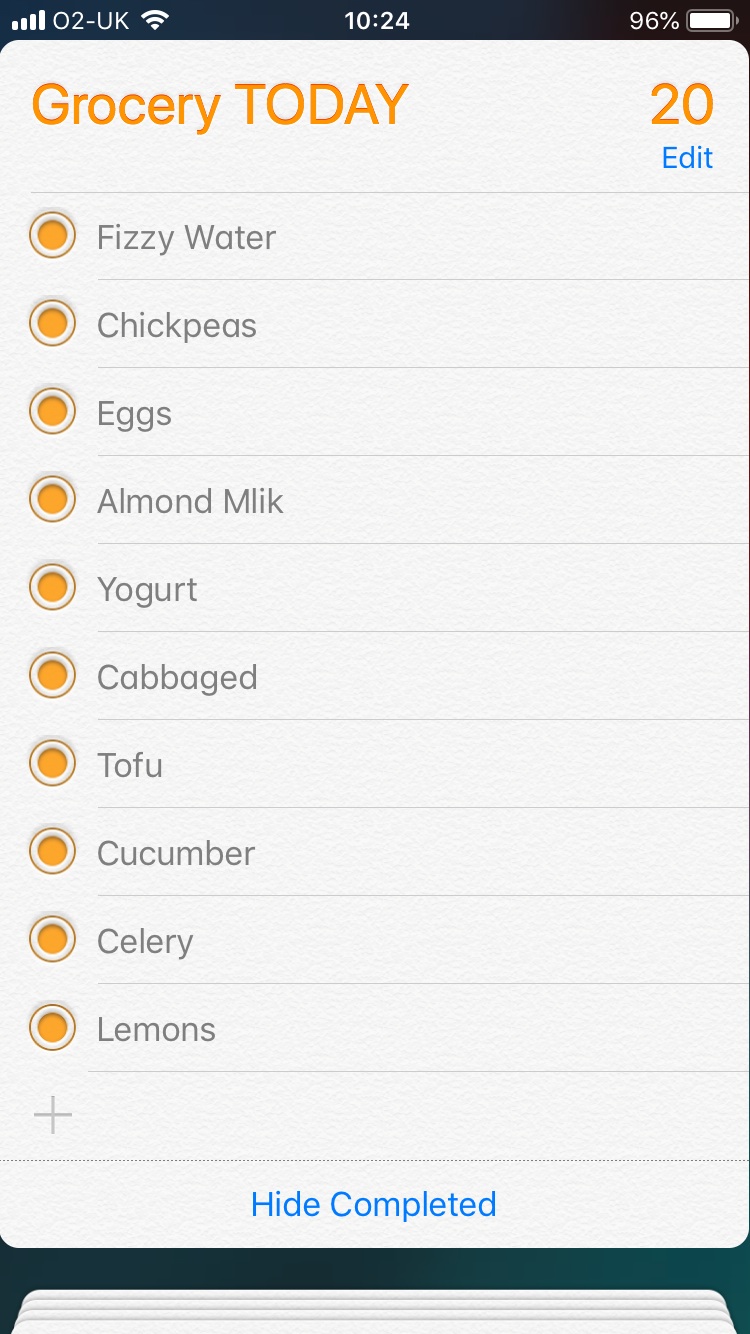

I realized recently that the thing I write the most is grocery lists. I have a document of my pantry essentials. I have a master grocery list. And then I have the list “Grocery TODAY.” I don’t much believe in the Hans Ulrich urgency model, but the capitalization of that list suggests that while the exhibition model might lack urgency, my groceries have it deeply. My list, and its completed items, are my own Sapphic fragments to my sustenance and luxuries. It is a deeply personal text, less personal than my receipts or a stool sample, but autobiographical nonetheless. Like my mother and grandmother before me, I insist on eating well.

This list is also full of shame for all my purchase of carbonated water in plastic bottles. And its ellipses are many – chocolate likely doesn’t appear because I dare not not have it. I wish this list could be time-stamped so it could show the changing seasons, and also to show how some things linger constantly unchecked, not as necessities, but signifiers of what I hope to eat and never do, horizons of a better life. But I should remind myself that, like poetry, ricotta is not a luxury.