Itziar Barrio

Some scholars have been encouraging people to move beyond place to just kind of think of everything maybe as space and so to get away from that dichotomy, or to come up with other language. For me place, because it's about meaning and meaning production, struck me as very important. The people that I was working with, the scientists, they are unaware of this Place/Space controversy so they use place with freedom and it means something specific to them. So what I decided to do in my research is to acknowledge this history of place and the problems with place, but to then still find a way that it can be used and used informatively. So when I use place I use it in its most colloquial sense, really a meaning filled location is how I think about place. So anywhere that someone has ascribed a particular feeling or attachment or a subjective way of knowing or thinking about to me that it is what a place is. Places change, they are static, so understanding how a place comes to be and maybe comes to be undone, produced by people and communities, is a very significant anthropological way of thinking about place.

It is in the text either spoken or written that you begin to see how things like metaphors and analogies let us know something about what these planets are in terms of places. There's a real fine line that planetary scientists has to walk. If they rely on metaphor and analogy too much they risk missing something. If you're only ever looking for Earth you're not going to see all the things that aren't Earth, but if you don't have metaphor and analogy as a little bit to guide you don't even know where to start looking. Metaphor and analogy are instrumental in the chatter, in the kind of off paper outside of the journal articles, conversations, that astronomers have with each other and with amongst themselves. But how a little bit of this gets stripped away as it goes further and further into the formalization, into the paper writing, in a way to reopen what kind of possibilities that might be.

So in science studies, in anthropology, and history of sciences one of the common themes and one I think is the most significant contributions of our field, is the idea that all science is constructed. This isn't to say that is made up or fake or wrong or misleading but that is the product of human work and that one doesn't just discover something but one asks a specific question and then comes up with specific methods and tools in order to answer that question. So all science is human constructed. Everything we know about planets is constructed and if you allow yourself to kind of philosophically take that to an extreme then you can say that the planet itself is also constructed. So a planet might be real but what we know about it and how we imagine it is 100% the work of human practice and therefore is constructed.

Excerpts from a conversation I had with professor of sociocultural anthropology at Yale University

Lisa R. Messeri, PhD (Placing Outer Space: An Earthly Ethnography of Other Worlds, 2016)

New York City, Summer 2018.

The imagination of space as a surface on which we are placed, the turning of space into time, the sharp separation of local place from the space out there; these are all ways of taming the challenge that the inherent spatiality of the world presents. Most often, they are unthought. Those who argue that Mozambique is just 'behind' do not (presumably) do so as a consequence of much deep pondering upon the nature of, and the relationship between, space and time. Their conceptualisation of space, its reduction to a dimension for the display/representation of different moments in time, is one assumes, implicit. In that they are not alone. One of the recurring motifs in what follows is just how little, actually, space is thought about explicitly. None the less, the persistent--

The politics of interrelations mirrors, then, the first proposition, that space too is a product of interrelations. Space does not exist prior to identities/entities and their relations. More generally I would argue that identities/entities, the relations 'between' them, and the spatiality which is part of them, are all co constitutive. Chantal Mouffe (1993, 1995), in particular, has written of how we might conceptualise the relational construction of political subjectivities. For her, identities and interrelations are constituted together. But spatiality may also be from the beginning integral to the constitution of those identities them selves, including political subjectivities. Moreover, specifically spatial identities (places, nations) can equally be reconceptualised in relational terms. Questions of the geographies of relations, and of the geographies of the necessity of their negotiation (in the widest sense of that term) run through the book If no space/place is a coherent seamless authenticity then one issue which is raised is the question of its internal negotiation. And if identities, both specifically spatial and otherwise, are indeed constructed relationally then that poses the question of the geography of those relations of construction. It raises questions of the politics of those geographies and of our relationship to and responsibility for them; and it raises, conversely and perhaps less expectedly, the potential geographies of our social responsibility.

Third, imagining space as always in process, as never a closed system, resonates with an increasingly vocal insistence within political discourses on the genuine openness of the future. It is an insistence founded in an attempt to escape the inexorability which so frequently characterises the grand narratives related by modernity. The frameworks of Progress, of Development and of Modernisation, and the succession of modes of production elaborated within Marxism, all propose scenarios in which the general directions of history, including the future, are known. However much it may be necessary to fight to bring them about, to engage in struggles for their achievement, there was always none the less a background conviction about the direction in which history was moving. Many today reject such a formulation and argue instead for a radical openness of the future, whether they argue it through radical democracy (for example Laclau, 1990; Laclau and Mouffe, 2001), through notions of active experimentation (as in Deleuze and Guattari, 1988; Deleuze and Parnet, 1987) or through certain approaches within queer theory (see as one instance Haver, 1997). Indeed, as Laclau in particular would most strongly argue, only if we conceive of the future as open can we seriously accept or engage in any genuine notion of politics. Only if the future is open is there any ground for a politics which can make a difference.

Excerpts from the book ‘For Space’ (SAGE, 2005) by geographer Doreen Massey.

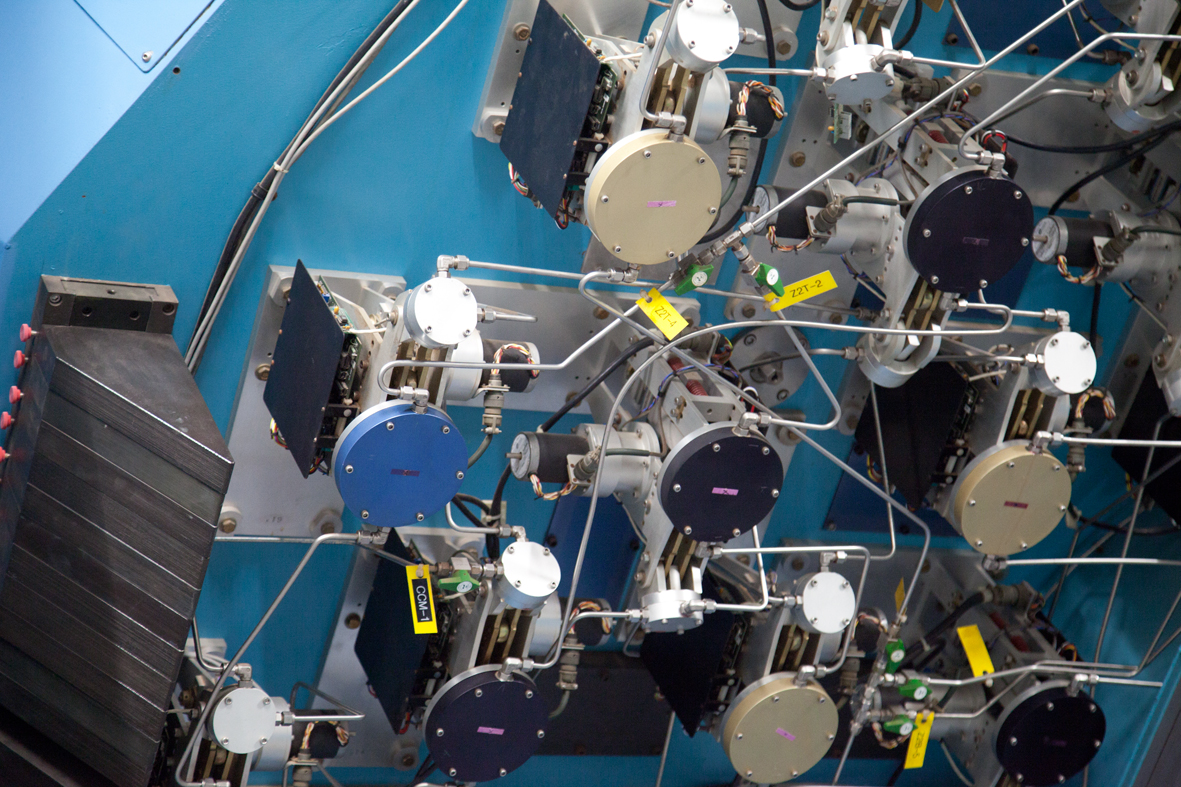

Telescope. Kitt Peak National Observatory. Tucson, AZ

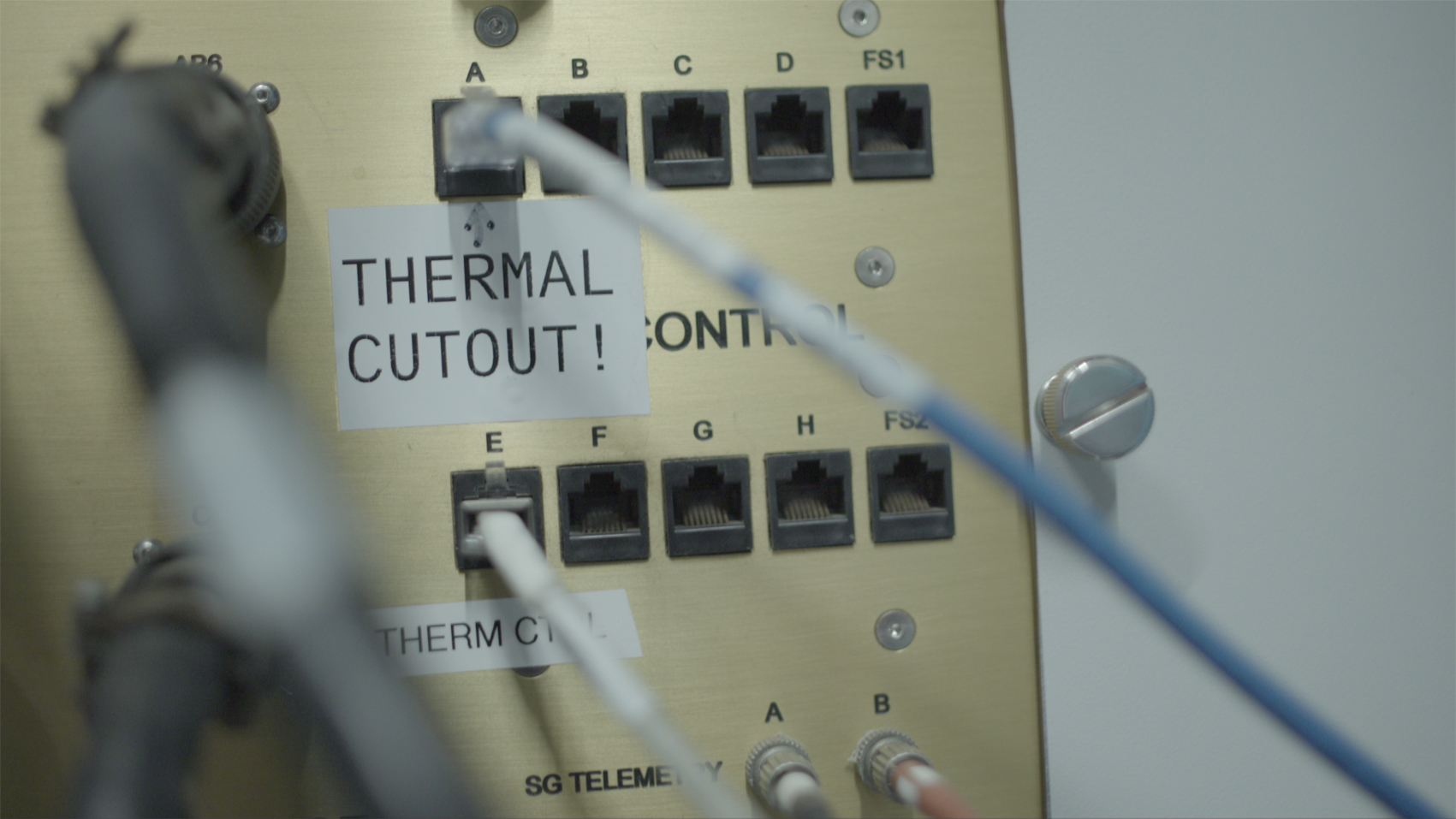

Telescope. Kitt Peak National Observatory. Tucson, AZ  ‘Warm room’ Kitt Peak National Observatory. Tucson, AZ

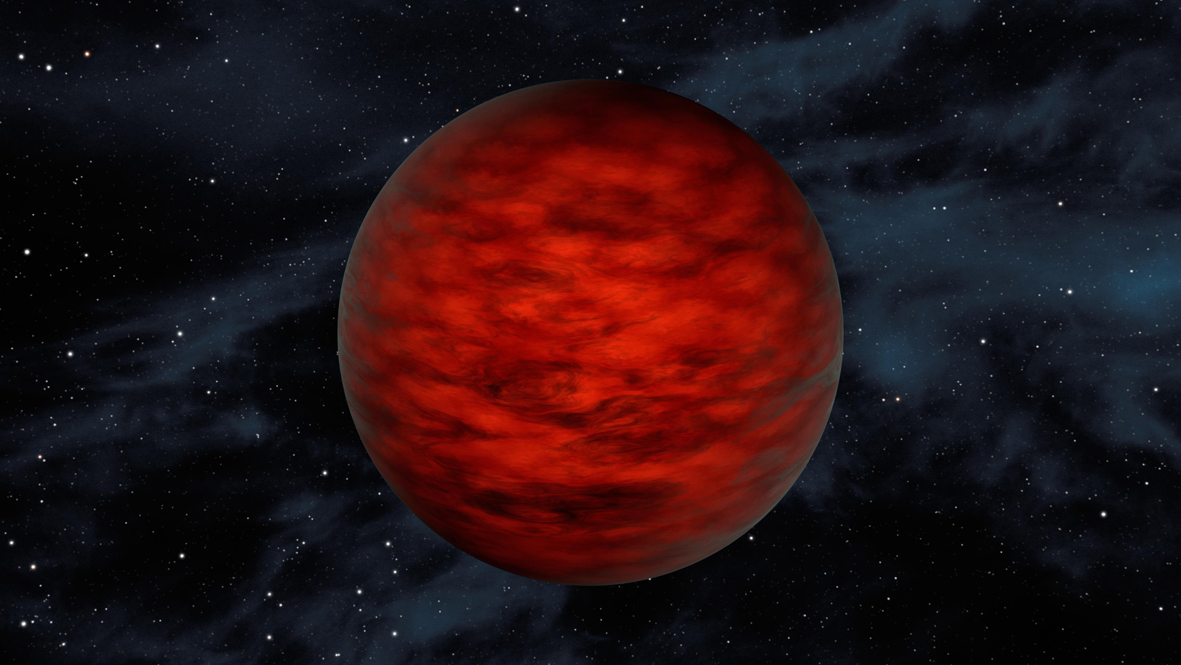

‘Warm room’ Kitt Peak National Observatory. Tucson, AZ Brown Dwarf. National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Brown Dwarf. National Aeronautics and Space Administration ’Warm room.’ Kitt Peak National Observatory. Tucson, AZ

’Warm room.’ Kitt Peak National Observatory. Tucson, AZ Telescope detail. Kitt Peak National Observatory. Tucson, AZ

Telescope detail. Kitt Peak National Observatory. Tucson, AZ  Bar LA CAVERNA. NYC

Bar LA CAVERNA. NYC Telescope detail. Kitt Peak National Observatory. Tucson, AZ

Telescope detail. Kitt Peak National Observatory. Tucson, AZ Video Still. A Demon that Slips into your Telescopes While You’re Dead tired and Blocks the Light. Itziar Barrio. 2020.

Video Still. A Demon that Slips into your Telescopes While You’re Dead tired and Blocks the Light. Itziar Barrio. 2020. Bar LA CAVERNA. NYC

Bar LA CAVERNA. NYC Kitt Peak National Observatory. Tucson, AZ

Kitt Peak National Observatory. Tucson, AZ