Assaf Evron

Erich Mendelohn's Park SynagogueIn 2019 I was invited by the curator Lisa Kurzner to visit Park Synagogue in Cleveland, Ohio for a potential project. Park Synagogue is one of four synagogues German Jewish architect Erich Mendelsohn built in the US. The project was never realized; however, a conglomerate of thoughts, research, and images was formed that I would like to share here.

Erich Mendelsohn is a man of the 20th Century, a man of many exiles. He was part of the German expressionist Avantguard of the teens and twenties. Among the many buildings he designed in Germany is the Einstein Tower in Potsdam, a sculpture and a building at the same time. He developed the streamlined modern department store and designed the Schocken stores across Germany. In 1933 with the rise of national socialism, Mendelsohn and his wife Luise fled to England. He split his time between London and Palestine collecting commissions in both places. In 1938, hoping to be more involved in the building of the developing country, he moved to Palestine. However, pretty quickly he realized that he would not receive the commissions he was hoping for, and in 1941 the Mendelsohns immigrated to the United States.

In the twenties, America had a significant influence on Mendelsohn. In 1924, he visited the US and published a photographic album based on his travels. Chicago, Detroit, Buffalo, and New York presented new architectural territories for him. Despite his criticism of American Capitalism (caption of allies island photo), he was fascinated with the American industry and the immense structures of grain elevators and silos. The utilitarian architecture, the organic nature of the structures (Letter Nov 7, 1947), and their matter-of-factness left a deep impression on young Mendelsohn and had a strong impact on his work in the twenties and thirties. However, in 1941, as an immigrant, his encounter with America was different.

As Erich and Luise Mendelsohn arrived in the US, with the support of his friend Frank Lloyd Wright, an exhibition of his works and drawings was presented at MOMA. The exhibition opened in November 1941, but with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the escalation of World War II, the exhibition did not receive any attention. Mendelsohn joined the American war effort, and with his knowledge of German architecture and infrastructure, he helped design A German Village in the Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, a test site for the bombing of Nazi Germany (Cabinet). Nevertheless, due to the strict immigration rules, Mendelsohn could not work as an architect and receive any building commissions until much later in 1946 when he became an American citizen. Despite the struggles of immigration, Mendelsohn kept his optimism and belief in the American Dream. In a letter to Julius Posener, he writes, “Work is everywhere, and a good worker works always as his own magnet. My migratory years will come to an end, and a new world will become my own. Where chances are plentiful, hazards don’t come. We Jews are used to it”.

Mendelsohn in America was living the life of the Wandering Jew. He was an architect in the autumn of his career on his third exile reinventing himself. At that point in his career, the personal and the professional intersected as never before. On the surface, it was a thing that a modernist architect could not afford, as there was no place for the personal in the so-called objective and functional world of architecture. However, the spiritual aspects of Judaism, the question of how to be a Jew in modern America in the shadow of WWII, and the difficulties of his years of immigration had stirred Mendelsohn’s practice in a new direction. He turned into himself and his community. During this US period, he mainly had built synagogues for communities across the Midwest: St. Louis (Missouri), Grand Rapids (Michigan), Minneapolis (Minnesota), and Cleveland (Ohio).

When Rabbi Armond Cohen from congregation Anshe Emet in Cleveland invited Mendelsohn in 1945 to discuss a commission for a new synagogue, Mendelsohn was very excited. He flew into Cleveland amid a snowstorm. Mendelson discussed with Rabbi Cohen his ideas about the design of the temple as a dome and having a tent-like structure shielding the arc. In that conversation, in a semi-comic remark, Mendelson said: “I am a one-eyed architect that can’t draw a straight line but the draftsmen in my office would generate perfect drawings for you” (based on the memories of Rabbi Cohen). On the surface a small anecdote, but looking at the building I could not stop seeing Mendelsohn’s eye.

In the short bio in the Mendelsohn archive at the kunstbibliotek in Berlin, the loss of the eye is described in these dry words: “In 1921, Mendelsohn’s left eye had to be removed due to cancer. The fact that this does not lead to any loss of business is due to the very good staff and employees, who worked in his office. Despite the accelerating inflation, he was able to realize large orders with his office in the early years of the Weimar Republic, including the conversion and expansion of the Rudolf Mosse publishing house in Berlin and the hat factory Friedrich Steinberg, Herrmann & Co. in Luckenwalde” (kunstbibliotek). The loss of the eye is presented here as a minor anecdote that should not interfere with the so-called objective and pragmatic image of a great architect of the 20th century—or this matter, the personal and the professional run on two parallel planes that should not intersect or interfere. However, Mendelsohn had a more complex understanding of objectivity in relation to architecture. “The analytic concept of architecture refuses vision; the visionary doesn’t understand analytic objectivity” (Letter Nov 7, 1947). For him, architecture is not a rationalist or a functionalist structure. Architecture, for him, is charged with meaning and significance. It is saturated with vision that is spiritual, cultural, and I would argue in the case of Park Synagogue, also psychoanalytical.

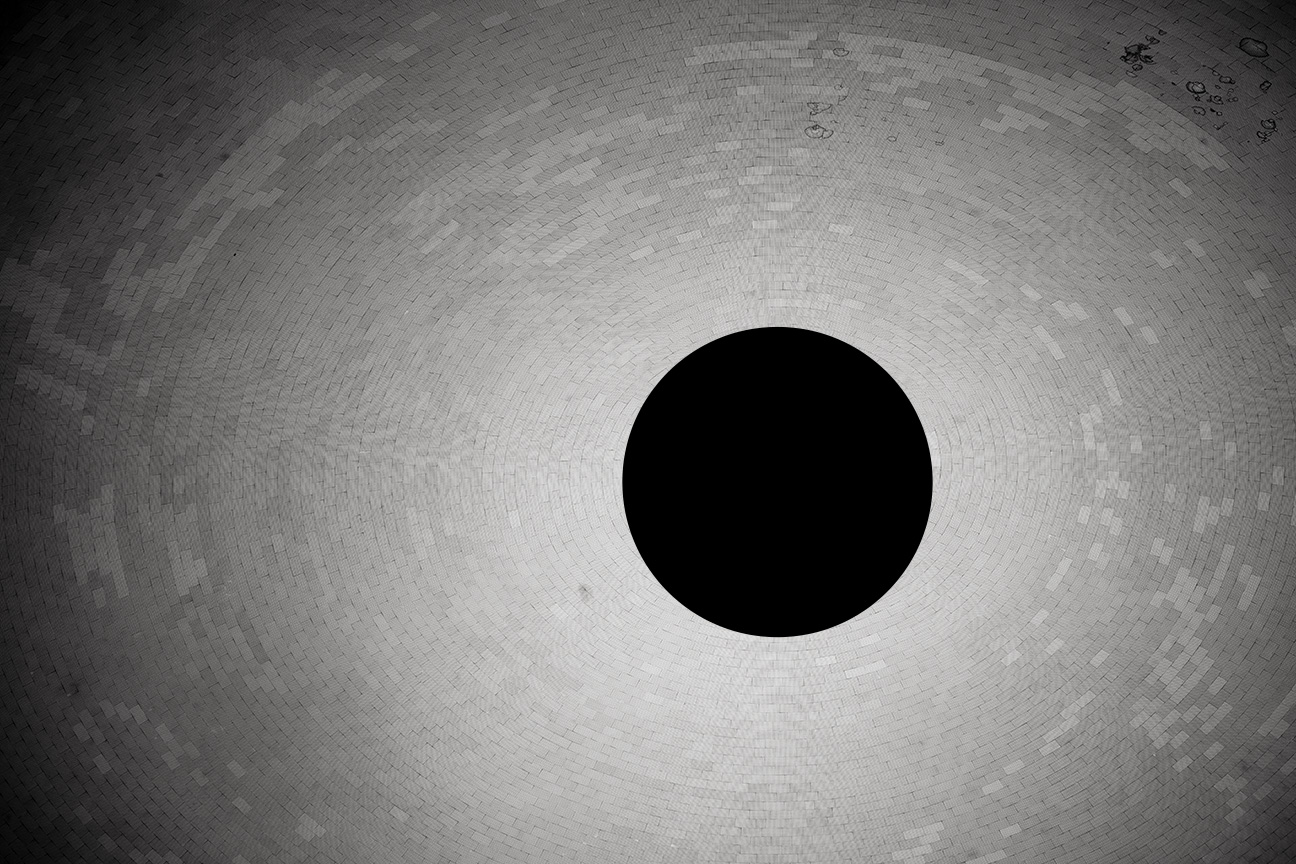

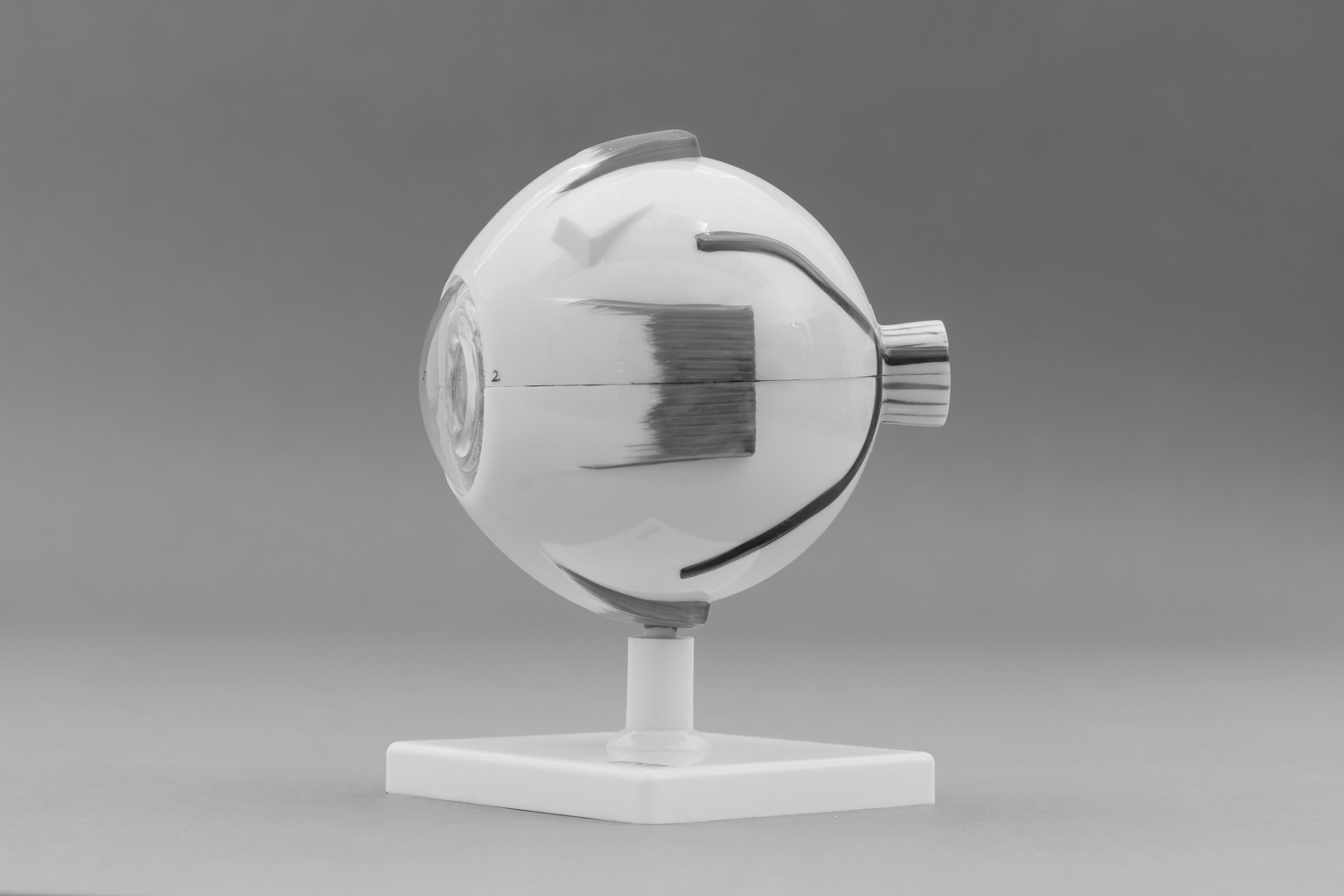

Once the story of the missing eye is introduced into the conversation, the architecture of Park Synagogue becomes saturated with Oculi. Every architectural feature in the building becomes an eye. The giant dome, the rounded windows, the light fixtures all become eyes—looking at you or for you to look through. Even the metalwork inspired by the Hebrew letter Shin resembles a clan of Cyclops holding hands.

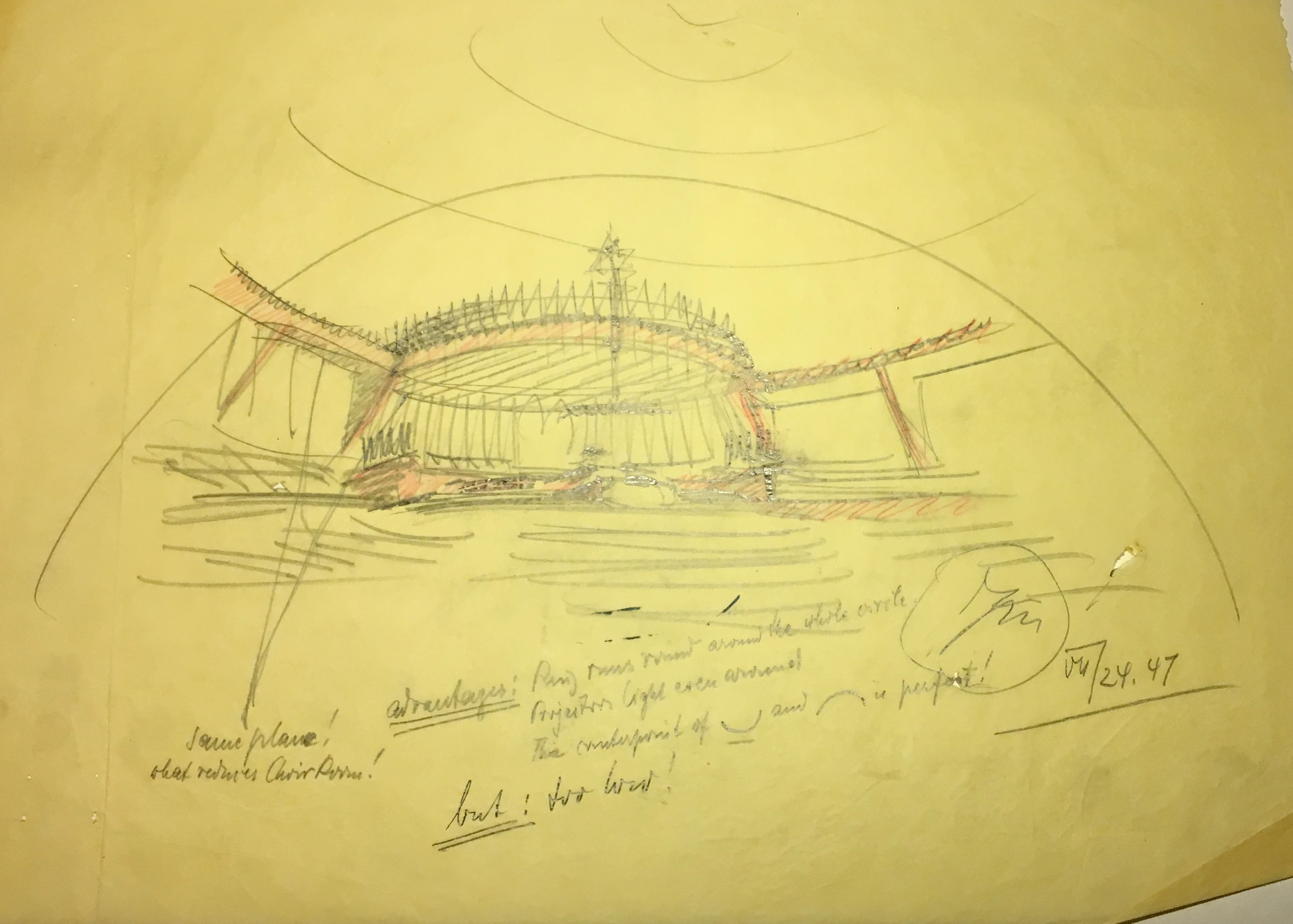

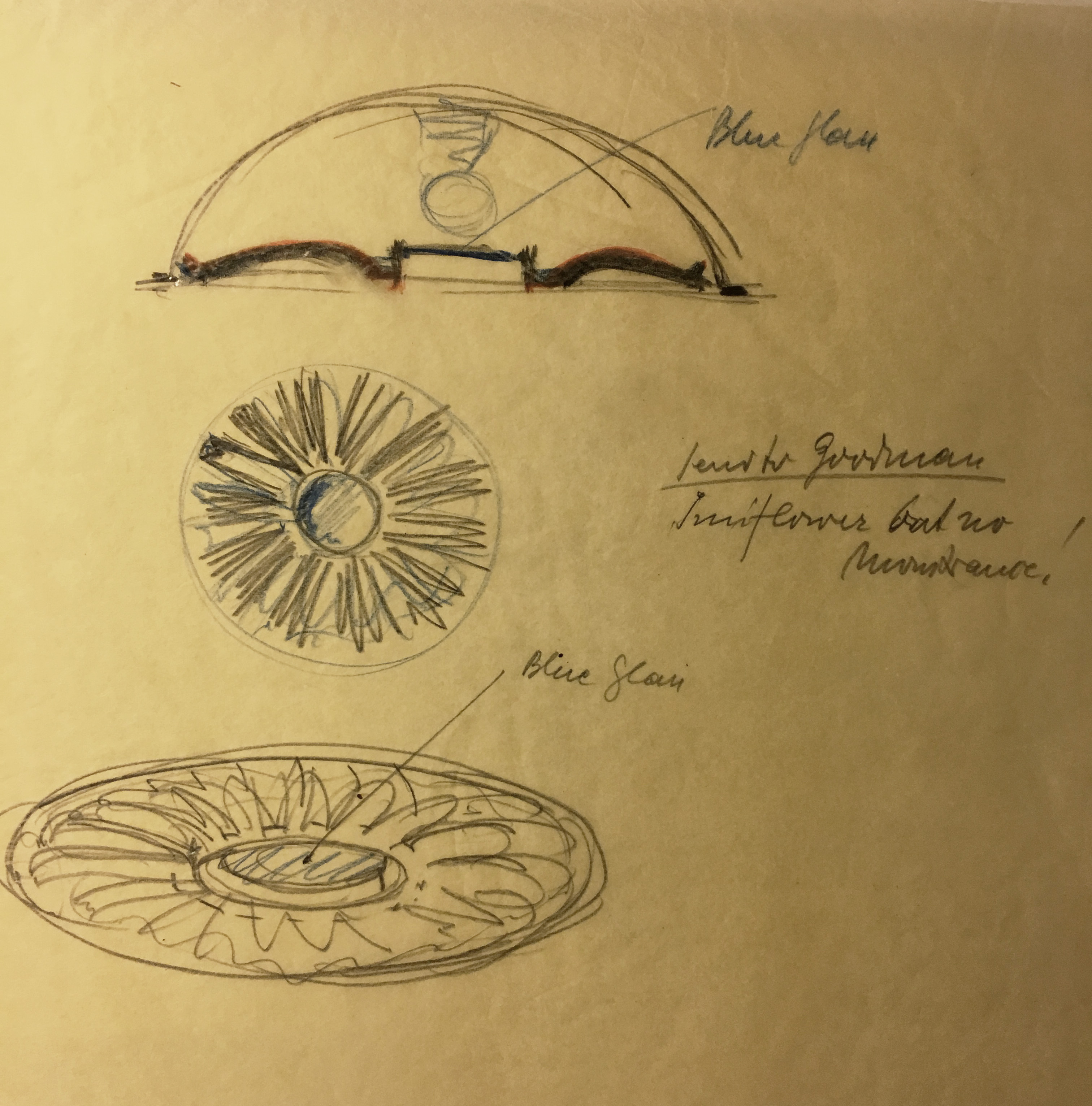

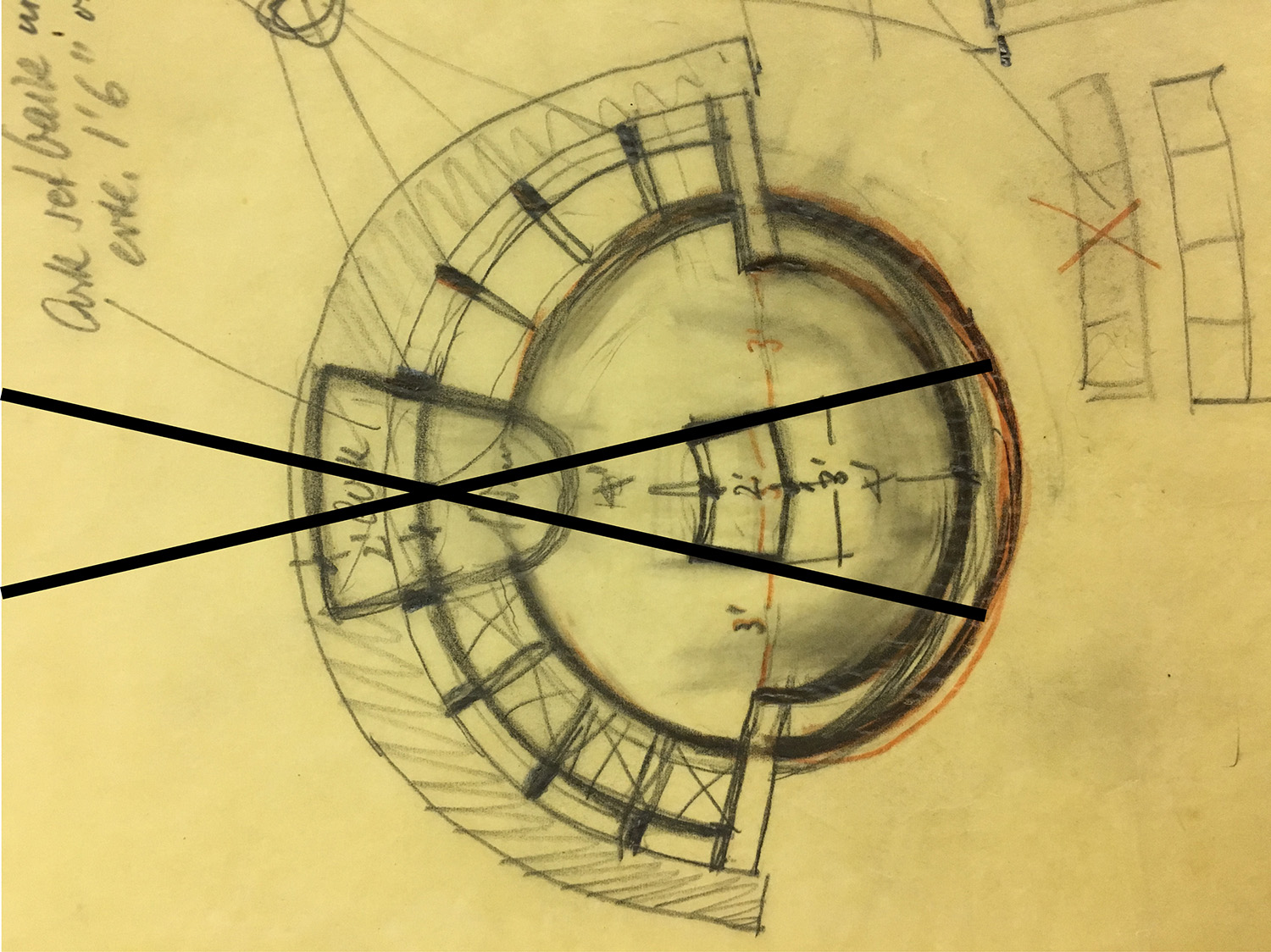

In “The Complete Works of Mendelsohn,” Bruno Zevi looks at the preparatory drawings for Park Synagogue. He focuses on the iconic sphere that characterizes Mendelsohn’s drawings throughout his career. In his sketches, Mendelsohn used the sphere to anchor the architecture under the sky and place it in a dynamic worldly environment. However, in the drawings for Park Synagogue, Zevi denotes that the celestial sphere and the dome or the cupola of the building are merged together. Zevi interprets this gesture as a metonymy; the dome stands in for the sky. It is also a poetic gesture, the crowd of worshippers gathering under the symbolic sky to pray. The idea of the dome as a sky is not new and has been applied throughout history since antiquity. However, Park Synagogue is the first and only building in Mendelsohn’s career with such a dramatic dome or Oculi.

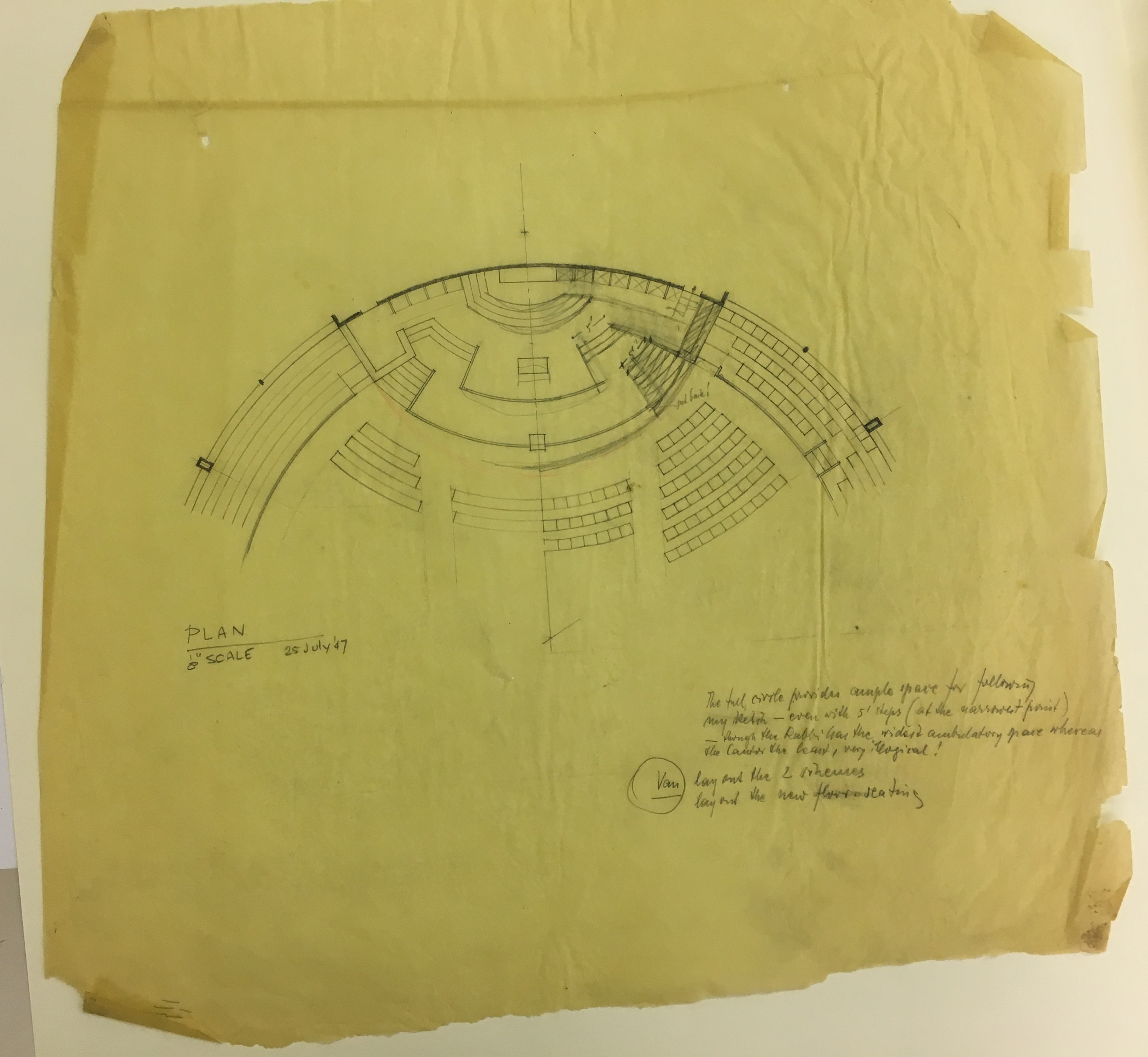

Looking at preparatory drawings and sketches can give great insight into architects’ ideas and thinking processes. Drawings can show the formal and conceptual development of ideas and disclose information that is not necessarily apparent in the accomplished building. drawings for Park Synagogue show that Mendelsohn’s absent eye might be more than an anecdote or a Freudian slip in his conversation with Rabbi Cohn. And perhaps the dome is not only standing in for the sky; maybe this is another one of Mendelsohn’s intelligible buildings similar to the hat factory.

The drawings for Park Synagogue show an explicit embodiment of the anatomy of an eye in the design of the building. The dome obviously operates as an oculus looking up at the sky, but the floor plan for the main congregation under the dome, as well as the annex, are surprisingly designed as an anatomical section eye. The lens, the retina, the iris, and the pupil are all present in the drawings. The retina is the back of the temple where the crowd enters the congregation, and the lens is where the arc resides at the optical focal point.

Thinking about Park Synagogue together with Mendelsohn’s drawings takes us back to the hat factory in Luckenwalde. Perhaps Park Synagogue is also one of these unique intelligible buildings but in a slightly different way. Unlike the clear and direct appearance of the hat factory, Park Synagogue does not look like an eye but rather has the structure of an eye as an organizing principle. The eye is sublimated and abstracted into the plan of the building. It operates on a formal and a metaphorical level to convey how ideas of spirituality can intertwine with architecture. But there is another voice hidden here, a personal one, the voice of a one-eyed architect on his third exile.

Images:

1. Erich Mendelsohn, Hat Factory Friedrich Steinberg Herrmann & Co. , Luckenwalde, Brandenburg, Germany

2. Erich Mendelsohn, Hat Factory Friedrich Steinberg Herrmann & Co. , Luckenwalde, Brandenburg, Germany

3. Richard D. Burke, Pizza Hut restaurant

4. Assaf Evron, Park Synagogue, Windows

5. Erich Mendelsohn, Drawing for Park Synagogue, Western Reserve Historical Society, CLE

6. Assaf Evron, Park Synagogue

7. Assaf Evron, Park Synagogue, Dome, Altered

8. Assaf Evron, Park Synagogue, Metal Work

9. Erich Mendelsohn, Drawing for Park Synagogue, Western Reserve Historical Society, CLE

10. Erich Mendelsohn, Drawing for Park Synagogue, Altered, Western Reserve Historical Society, CLE

11. Assaf Evron, Anatomical Model of an Eye

12. Erich Mendelsohn, Drawing for Park Synagogue,Western Reserve Historical Society, CLE

13. Assaf Evron, Park Synagogue, Doors

1. Erich Mendelsohn, Hat Factory Friedrich Steinberg Herrmann & Co. , Luckenwalde, Brandenburg, Germany

2. Erich Mendelsohn, Hat Factory Friedrich Steinberg Herrmann & Co. , Luckenwalde, Brandenburg, Germany

3. Richard D. Burke, Pizza Hut restaurant

4. Assaf Evron, Park Synagogue, Windows

5. Erich Mendelsohn, Drawing for Park Synagogue, Western Reserve Historical Society, CLE

6. Assaf Evron, Park Synagogue

7. Assaf Evron, Park Synagogue, Dome, Altered

8. Assaf Evron, Park Synagogue, Metal Work

9. Erich Mendelsohn, Drawing for Park Synagogue, Western Reserve Historical Society, CLE

10. Erich Mendelsohn, Drawing for Park Synagogue, Altered, Western Reserve Historical Society, CLE

11. Assaf Evron, Anatomical Model of an Eye

12. Erich Mendelsohn, Drawing for Park Synagogue,Western Reserve Historical Society, CLE

13. Assaf Evron, Park Synagogue, Doors