Enrique Ramirez

To The Pole Star

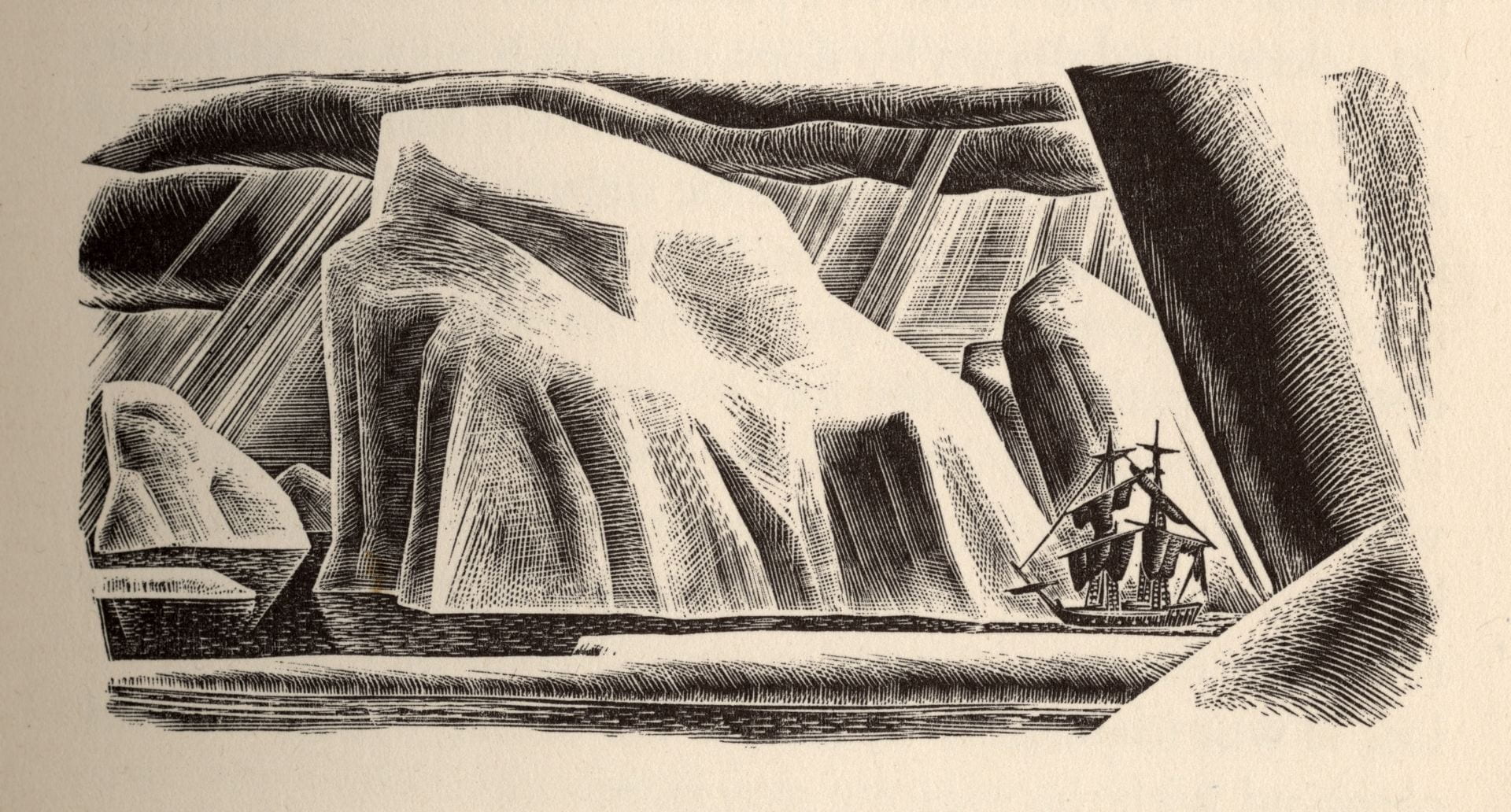

Lynd Ward, Wood-engraved illustration for Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley's Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus. New York: Harrison Smith and Robert Haas, 1934. Lynd Ward Wood Engravings and Other Graphic Art, Pennsylvania State University, Special Collections Library.

Amid the northward journeys of my youth, a desert. Not the kind with spiny cacti bristling from the baked earth. No, in this desert, there is only a stillness of the kind that makes a day like this ever so more frigid and desolate.

The sun hangs in a cloudless sky. The air bristles with needles. This is winter in suburban Chicago. Evanston, to be exact, less than a mile from the shore of Lake Michigan. I am unprepared for this weather, so unlike anything I had ever known growing up in the Caribbean and the Gulf Coast. The threadbare car coat I wear belonged to my father, but I cannot recall whether this was the coat he purchased for a business trip to Montréal back in the 1970s. My alpaca wool hat was supposedly a kind worn in Peru. I bought it at a store not far from the El called, laughably, The Mexican Store. On my hands are unlined leather work gloves, a kind that may have been worn while operating a lawn mower.

The skies turned dark, as they often did in the colder months. I looked up and imagined a map of the skies. Polaris hung there, ensnared in a dense weave of isobars and isotherms above me. Every shallow dip in this fabric brought a mass of frigid air, covering everything with a thin layer of ice. Here, on this street, it registered as heavy snowfall. Sheets of snow fell from skies as if from a giant unburdening, titans in the air releasing an epoch of pent-up cold on the unsuspecting world below.

In this snowstorm, a bookstore. It was called Great Expectations, which, in retrospect, was not so much a literary name, but an indication of its owners’ unabashed optimism. This is where one went for refuge, and the rewards were great. I do not remember much of about the exterior (who does), but inside, it looked like the aftermath of a storm—a storm of books. Imagine being inside a house, and now imagine it cast adrift in an expanse of water. You look at the white caps only to realize that they are not foamy, cresting waves. They are pages of opened books, fanned apart, rustling in the violent winds. They undulate in giant, epic swells that appear as moving mountains, or rather giant, slovenly piles that stalk the horizon. You see these through a large window framing this violent scene. A wave crashes through, and the inside is strewn with piles and piles of books. There is no logic, no order. You hold on to a pillar, searching for familiar titles as if they were life preservers, hoping that holding on to them will keep you moored. But this is before you surrender to the undertow. You are adrift, perhaps like Ophelia, going where the books take you, letting them weigh you down.

As I recovered, things began to reveal themselves to me slowly. I saw the owner, or at least, a man who I thought was the owner. He was a large man with a gray beard. He wore a red tartan shirt and suspenders that hoisted his fading jeans. He read a small paperback and occasionally turned the knob on a stereo console behind him. He may have been playing any kind of music. These sounds are lost to time. But there are things that I still recall in sharp detail. Like the cats. They sat on stacks of books like slovenly sphinxes. One even threaded its slinky body between my feet as I browsed a bookshelf. There was no reason here, only atmosphere. Yet there were some places in here where the books were arranged in manner so obvious that it was halting. All the Penguin Classics, for example, were kept in a room in the back of the store. The titles were not alphabetically arranged, however. They were grouped according to the colored flashing at the top of the spine. German and French titles were in yellow. Classics in purple. Chinese, Arabic, and Japanese in green. In the grouping of American and British titles, with their distinctive red flashing, I found Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. My knowledge of this book was only through movies stills, comic books, and Halloween costumes. And here I was, in a cocoon of books, swaddled by words. I was comfortable, not wanting to venture out into the storm. I found a comfortable chair and began to read.

I spent the rest of that afternoon with Frankenstein. Reading it was a kind of voyage, treacherous, sometimes confusing. I encountered tricky passages and strange words, and before I was left adrift in these shoals, I collected myself and walked to a giant open dictionary mounted on a wooden lectern. It sat there like a ship’s helm, and from this vantage point I looked at the world outside. The pale wintry light flowed through the shop window, casting a dull glow on the stacks of books. Gusts of wind rattled the pane, and through it I saw the snow drifts accumulate and cover the world outside in a powdery swirl.

I held on to this image when I got back to Frankenstein. It was no longer a horror fantasy, but an Arctic adventure where one of the most famous creatures ever committed to the page drives a sled team through the boreal night. The cold fascinated me, born in Texas and raised in the Caribbean, and never having experienced anything like winter until a couple of days earlier. That was when I stood on the edge of campus, on the shore of Lake Michigan, bracing myself against the freezing gale and staring at the beach rocks covered by sheets of broken ice. I had never seen anything like it. The ice became giant shards of glass, a treacherous valley of crags and planes I would picture as the setting for Frankenstein here on this snowy afternoon. I bought the book and a small paperback atlas and walked home in time for dinner. Why an atlas? Something about Frankenstein required it. I wanted to anchor these images of vast Arctic landscapes to something known. I used the atlas as a kind of reference in the same way I would use a dictionary or thesaurus. This led to a discovery. The action in Frankenstein moved along a northerly course. Victor Frankenstein is Genevese, born in Naples, at forty degrees north latitude. He studies at the University of Ingolstadt, in Bavaria, at forty-eight degrees north latitude, which is also the place where he assembles his creature. In the Orkney Islands, around fifty-nine degrees north latitude, Frankenstein begins—and abandons—experiments to create a female companion for his humanoid male. And as for the novel, it is written in an epistolary fashion, secreted away in a packet of letters written by one Captain Walton while on a brig, first near Saint Petersburg, also fifty-nine degrees north latitude, then near Arkhangelsk (Archangel), on the shores of the White Sea, at sixty-four degrees north latitude. Once north of this bearing, which we can assume is somewhere near seventy degrees north latitude, Captain Walton sees the Aurora Borealis and has his first sightings of Victor Frankenstein’s sled team. Frankenstein is in hot pursuit, which means that his creature, also on a sled team, may be well above eighty degrees north latitude.

Looking back at the years since this discovery, I understand my education has been one where I too have been reading towards the northern latitudes. Several years later, as a law student living in Washington, DC, I learned the importance of incorporating maps into fictions and landscapes. I was taking a class with an English lawyer who made a career of working on territorial disputes before the International Court of Justice. In his honeyed gravitas, he described the international law of territory as a tangle of meridians and parallels, a terrain where history and self-determination were almost always at odds. His knowledge of a particular case drew on his broad knowledge base, a chance to argue that whether drawing a coastline on the Barents Seas or settling a boundary between Botswana and Namibia, these were issues rooted in the annals of the Justinian Code or in the Commentaries of Accursius. So was his latest case: a territorial dispute concerning the status of the waters between the Eastern coast of Greenland and the Norwegian island of Jan Mayen. In the case, the International Court of Justice created boundary zones between Greenland and Jan Mayen that respected both international law as well as the behaviors of Denmark and Norway throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It was important to have a map in these cases, for the legal arguments made no sense without any kind of guide to the spaces that were being deliberated in the tony tribunals of international law.

Without maps, international law is only dead reckoning. The outcome of one dispute can only be located by fixing a previous one. This was the lesson of these disputes between Denmark and Norway. The Jan Mayen case had its origins in 1933 with the Eastern Greenland Case, the only decision that established principles of territorial sovereignty in the Polar regions. This dispute began in 1931 when an expedition from the Norwegian Arctic Trading Company planted a flag on Myggbukta, a small whaling station on King Christian X Land on Greenland’s eastern shore. This act set off a chain of diplomatic cables claiming that Norway was violating Danish territorial sovereignty. In a previous treaty, Denmark agreed not to make any claims on Spitsbergen (now known as Svalbard) if Norway left Greenland alone. As contentious as this case may have seemed, the two countries agreed to have an international tribunal settle the dispute. The Permanent Court of International Justice—established by League of Nations in 1922—considered the geographical and historical factors at play. It looked at the claims from a broader environmental, geographical, and historical context. Drifting ice sheets and polar bear migrations showed that gaining a foothold in this land was tricky. Language was also an issue, for there was little agreement among the medieval Nordic sagas concerning crucial historical details. At the heart of the Grœnlendiga saga, or “History of the Greenlanders,” is the story of Bjarni Herjólfsson, plying the northern oceans in hopes of joining his father, Herjólfr Bárðarson, who founded the settlement of Herjolfsnes on the southernmost tip of Greenland in the tenth century. And though this colony would be settled continuously for the next half century, the account of its founding is absent from another important Nordic saga. In Sturla Thórdarson’s Hákonarsaga, Greenland was originally two independent colonies: Vestrigybd, on the western coast of Greenland, and Estrigybd on the East. Both were ruled by Eerik Raude, also known as Erik Thorvaldsson, or Erik the Red, and both colonies became part of Norway in 1261.

In 1993, my teacher arrived at Jan Mayen and Greenland’s eastern coast with a team of surveyors and lawyers. They were there to verify the legal and geographical claims that were laid out in the 1933 case. At Jan Mayen, they walked along the black volcanic sands along the eastern coast. They visited remnants from other epochs: graves of seventeenth-century Dutch sailors; abandoned equipment, rusted and worn, once part of a Norwegian meteorological station; and the crumpled remains of Luftwaffe bombers. Wearing brightly colored parkas, and armed with radio transmitters, they trundled along the rocks and ice fields, always keeping sight of the massive Beerenberg volcano, and active presence in the land. Successive eruptions in 1970 and 1985 created lava fields that spread to the north, altering the island’s terrain, and increasing its surface area.

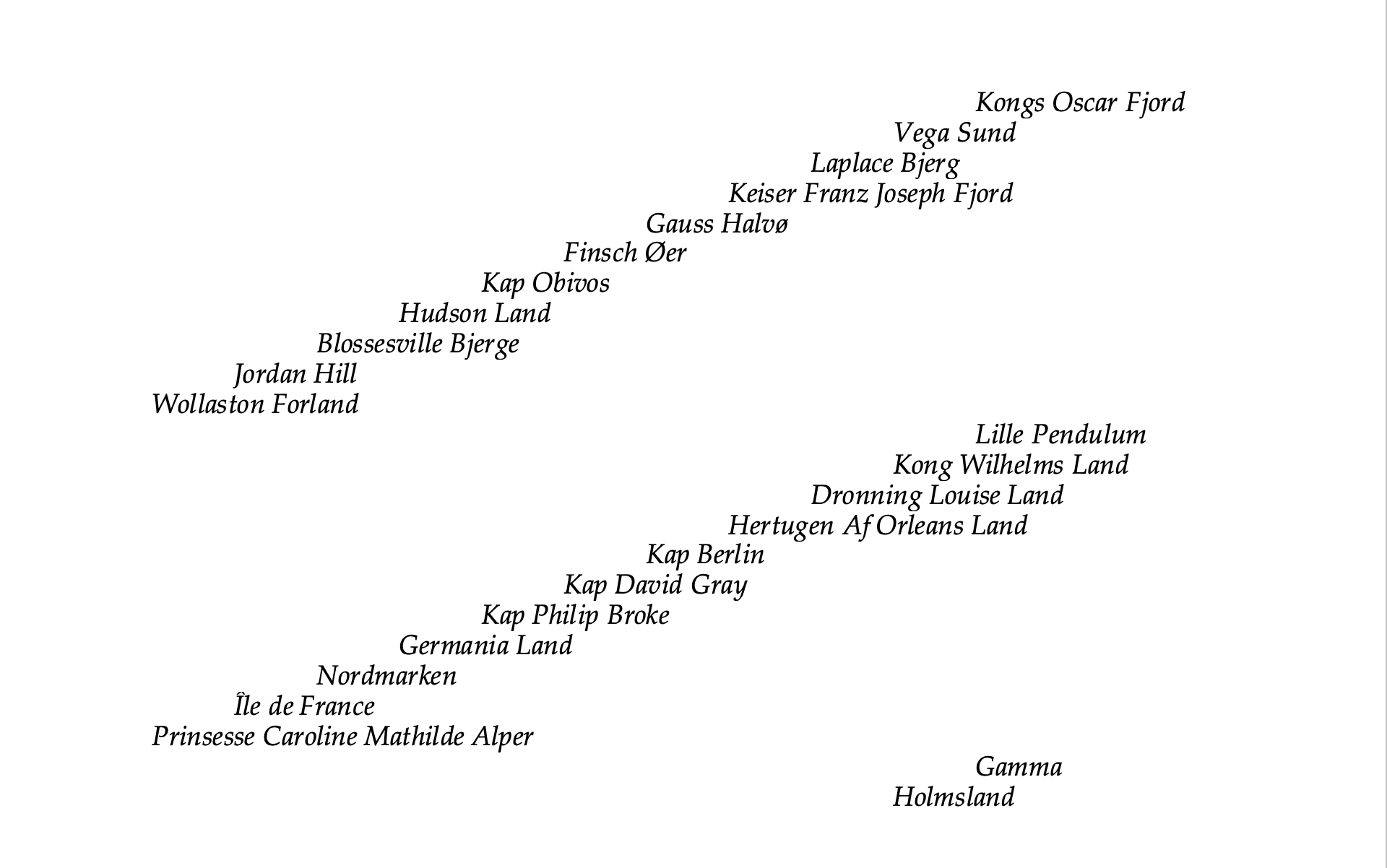

They crossed the Denmark strait and sailed up the coast of Eastern Greenland from Scoresby Sound to Shannon Island. Their guide was a map with hundreds of small dots, each labeled “Trapper’s Hut” and scattered among inlets, sounds, and fjords. It was an architectural archipelago, or even a triangulation net draped over this desolate and forbidding land, a true settlement pattern. Along the crenelated coast, both land and water carried the names of dead royals and distant worlds,

Amid the northward journeys of my youth, a desert. Not the kind with spiny cacti bristling from the baked earth. No, in this desert, there is only a stillness of the kind that makes a day like this ever so more frigid and desolate.

The sun hangs in a cloudless sky. The air bristles with needles. This is winter in suburban Chicago. Evanston, to be exact, less than a mile from the shore of Lake Michigan. I am unprepared for this weather, so unlike anything I had ever known growing up in the Caribbean and the Gulf Coast. The threadbare car coat I wear belonged to my father, but I cannot recall whether this was the coat he purchased for a business trip to Montréal back in the 1970s. My alpaca wool hat was supposedly a kind worn in Peru. I bought it at a store not far from the El called, laughably, The Mexican Store. On my hands are unlined leather work gloves, a kind that may have been worn while operating a lawn mower.

The skies turned dark, as they often did in the colder months. I looked up and imagined a map of the skies. Polaris hung there, ensnared in a dense weave of isobars and isotherms above me. Every shallow dip in this fabric brought a mass of frigid air, covering everything with a thin layer of ice. Here, on this street, it registered as heavy snowfall. Sheets of snow fell from skies as if from a giant unburdening, titans in the air releasing an epoch of pent-up cold on the unsuspecting world below.

In this snowstorm, a bookstore. It was called Great Expectations, which, in retrospect, was not so much a literary name, but an indication of its owners’ unabashed optimism. This is where one went for refuge, and the rewards were great. I do not remember much of about the exterior (who does), but inside, it looked like the aftermath of a storm—a storm of books. Imagine being inside a house, and now imagine it cast adrift in an expanse of water. You look at the white caps only to realize that they are not foamy, cresting waves. They are pages of opened books, fanned apart, rustling in the violent winds. They undulate in giant, epic swells that appear as moving mountains, or rather giant, slovenly piles that stalk the horizon. You see these through a large window framing this violent scene. A wave crashes through, and the inside is strewn with piles and piles of books. There is no logic, no order. You hold on to a pillar, searching for familiar titles as if they were life preservers, hoping that holding on to them will keep you moored. But this is before you surrender to the undertow. You are adrift, perhaps like Ophelia, going where the books take you, letting them weigh you down.

As I recovered, things began to reveal themselves to me slowly. I saw the owner, or at least, a man who I thought was the owner. He was a large man with a gray beard. He wore a red tartan shirt and suspenders that hoisted his fading jeans. He read a small paperback and occasionally turned the knob on a stereo console behind him. He may have been playing any kind of music. These sounds are lost to time. But there are things that I still recall in sharp detail. Like the cats. They sat on stacks of books like slovenly sphinxes. One even threaded its slinky body between my feet as I browsed a bookshelf. There was no reason here, only atmosphere. Yet there were some places in here where the books were arranged in manner so obvious that it was halting. All the Penguin Classics, for example, were kept in a room in the back of the store. The titles were not alphabetically arranged, however. They were grouped according to the colored flashing at the top of the spine. German and French titles were in yellow. Classics in purple. Chinese, Arabic, and Japanese in green. In the grouping of American and British titles, with their distinctive red flashing, I found Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. My knowledge of this book was only through movies stills, comic books, and Halloween costumes. And here I was, in a cocoon of books, swaddled by words. I was comfortable, not wanting to venture out into the storm. I found a comfortable chair and began to read.

I spent the rest of that afternoon with Frankenstein. Reading it was a kind of voyage, treacherous, sometimes confusing. I encountered tricky passages and strange words, and before I was left adrift in these shoals, I collected myself and walked to a giant open dictionary mounted on a wooden lectern. It sat there like a ship’s helm, and from this vantage point I looked at the world outside. The pale wintry light flowed through the shop window, casting a dull glow on the stacks of books. Gusts of wind rattled the pane, and through it I saw the snow drifts accumulate and cover the world outside in a powdery swirl.

I held on to this image when I got back to Frankenstein. It was no longer a horror fantasy, but an Arctic adventure where one of the most famous creatures ever committed to the page drives a sled team through the boreal night. The cold fascinated me, born in Texas and raised in the Caribbean, and never having experienced anything like winter until a couple of days earlier. That was when I stood on the edge of campus, on the shore of Lake Michigan, bracing myself against the freezing gale and staring at the beach rocks covered by sheets of broken ice. I had never seen anything like it. The ice became giant shards of glass, a treacherous valley of crags and planes I would picture as the setting for Frankenstein here on this snowy afternoon. I bought the book and a small paperback atlas and walked home in time for dinner. Why an atlas? Something about Frankenstein required it. I wanted to anchor these images of vast Arctic landscapes to something known. I used the atlas as a kind of reference in the same way I would use a dictionary or thesaurus. This led to a discovery. The action in Frankenstein moved along a northerly course. Victor Frankenstein is Genevese, born in Naples, at forty degrees north latitude. He studies at the University of Ingolstadt, in Bavaria, at forty-eight degrees north latitude, which is also the place where he assembles his creature. In the Orkney Islands, around fifty-nine degrees north latitude, Frankenstein begins—and abandons—experiments to create a female companion for his humanoid male. And as for the novel, it is written in an epistolary fashion, secreted away in a packet of letters written by one Captain Walton while on a brig, first near Saint Petersburg, also fifty-nine degrees north latitude, then near Arkhangelsk (Archangel), on the shores of the White Sea, at sixty-four degrees north latitude. Once north of this bearing, which we can assume is somewhere near seventy degrees north latitude, Captain Walton sees the Aurora Borealis and has his first sightings of Victor Frankenstein’s sled team. Frankenstein is in hot pursuit, which means that his creature, also on a sled team, may be well above eighty degrees north latitude.

Looking back at the years since this discovery, I understand my education has been one where I too have been reading towards the northern latitudes. Several years later, as a law student living in Washington, DC, I learned the importance of incorporating maps into fictions and landscapes. I was taking a class with an English lawyer who made a career of working on territorial disputes before the International Court of Justice. In his honeyed gravitas, he described the international law of territory as a tangle of meridians and parallels, a terrain where history and self-determination were almost always at odds. His knowledge of a particular case drew on his broad knowledge base, a chance to argue that whether drawing a coastline on the Barents Seas or settling a boundary between Botswana and Namibia, these were issues rooted in the annals of the Justinian Code or in the Commentaries of Accursius. So was his latest case: a territorial dispute concerning the status of the waters between the Eastern coast of Greenland and the Norwegian island of Jan Mayen. In the case, the International Court of Justice created boundary zones between Greenland and Jan Mayen that respected both international law as well as the behaviors of Denmark and Norway throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It was important to have a map in these cases, for the legal arguments made no sense without any kind of guide to the spaces that were being deliberated in the tony tribunals of international law.

Without maps, international law is only dead reckoning. The outcome of one dispute can only be located by fixing a previous one. This was the lesson of these disputes between Denmark and Norway. The Jan Mayen case had its origins in 1933 with the Eastern Greenland Case, the only decision that established principles of territorial sovereignty in the Polar regions. This dispute began in 1931 when an expedition from the Norwegian Arctic Trading Company planted a flag on Myggbukta, a small whaling station on King Christian X Land on Greenland’s eastern shore. This act set off a chain of diplomatic cables claiming that Norway was violating Danish territorial sovereignty. In a previous treaty, Denmark agreed not to make any claims on Spitsbergen (now known as Svalbard) if Norway left Greenland alone. As contentious as this case may have seemed, the two countries agreed to have an international tribunal settle the dispute. The Permanent Court of International Justice—established by League of Nations in 1922—considered the geographical and historical factors at play. It looked at the claims from a broader environmental, geographical, and historical context. Drifting ice sheets and polar bear migrations showed that gaining a foothold in this land was tricky. Language was also an issue, for there was little agreement among the medieval Nordic sagas concerning crucial historical details. At the heart of the Grœnlendiga saga, or “History of the Greenlanders,” is the story of Bjarni Herjólfsson, plying the northern oceans in hopes of joining his father, Herjólfr Bárðarson, who founded the settlement of Herjolfsnes on the southernmost tip of Greenland in the tenth century. And though this colony would be settled continuously for the next half century, the account of its founding is absent from another important Nordic saga. In Sturla Thórdarson’s Hákonarsaga, Greenland was originally two independent colonies: Vestrigybd, on the western coast of Greenland, and Estrigybd on the East. Both were ruled by Eerik Raude, also known as Erik Thorvaldsson, or Erik the Red, and both colonies became part of Norway in 1261.

In 1993, my teacher arrived at Jan Mayen and Greenland’s eastern coast with a team of surveyors and lawyers. They were there to verify the legal and geographical claims that were laid out in the 1933 case. At Jan Mayen, they walked along the black volcanic sands along the eastern coast. They visited remnants from other epochs: graves of seventeenth-century Dutch sailors; abandoned equipment, rusted and worn, once part of a Norwegian meteorological station; and the crumpled remains of Luftwaffe bombers. Wearing brightly colored parkas, and armed with radio transmitters, they trundled along the rocks and ice fields, always keeping sight of the massive Beerenberg volcano, and active presence in the land. Successive eruptions in 1970 and 1985 created lava fields that spread to the north, altering the island’s terrain, and increasing its surface area.

They crossed the Denmark strait and sailed up the coast of Eastern Greenland from Scoresby Sound to Shannon Island. Their guide was a map with hundreds of small dots, each labeled “Trapper’s Hut” and scattered among inlets, sounds, and fjords. It was an architectural archipelago, or even a triangulation net draped over this desolate and forbidding land, a true settlement pattern. Along the crenelated coast, both land and water carried the names of dead royals and distant worlds,

It was a journey north through the links on a chain of title, a rambling meridian that tracked along the original line of settlement described in the Hákonarsaga as a voyage “right up to the Pole Star.”

Enrique Ramirez is a writer and historian of art and architecture. His work considers histories of landscapes, buildings, and cities within larger cultures of literary and artistic production in Europe and the Americas.