Lisa Tan

Mere Document

Beverly was married to a poet. That’s how she ended up living in Westbeth. I once saw her husband duck to hide behind the sofa, as I passed their common area on my way to the room where she held our weekly sessions.

She’d taken me on in her retirement because she was interested in the Asian American psyche (her words). Everything in the loft was thoroughly lived in—most of all Beverly herself—she was ancient. She must’ve been among Westbeth’s early residents, some of whom are art world luminaries. Lorraine O’Grady, Hans Haacke, the late Diane Arbus. But most of the artists, writers, dancers, musicians, filmmakers, activists, are not as readily known.

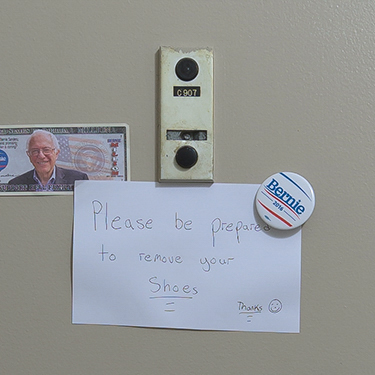

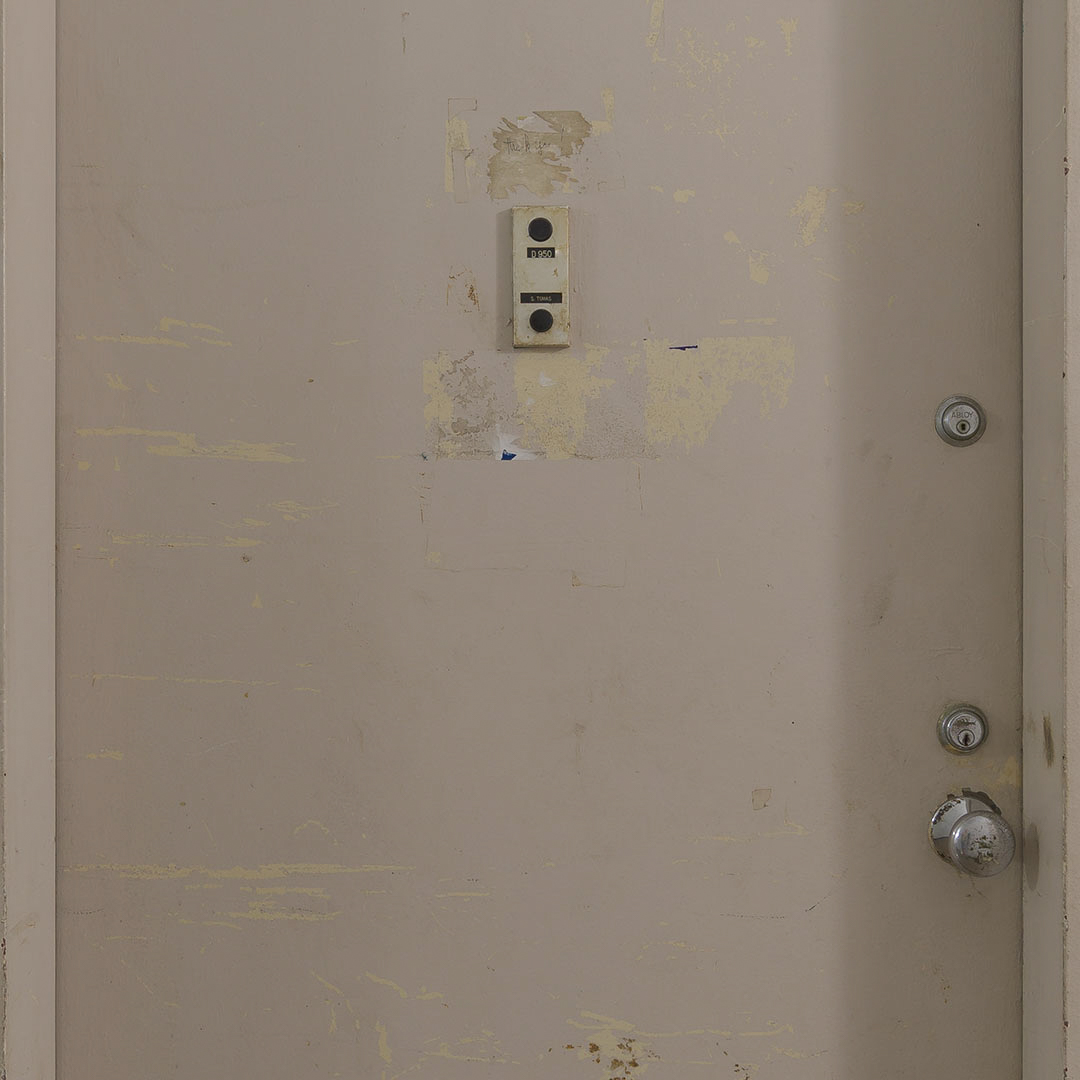

Therapy is good, if for nothing else, than for the ritual it creates outside of work. Westbeth had the symbols to lend, by way of its tenant’s doors. The corridors became a kind of processional walkway and a yellow triangle on Beverly’s door consecrated each of our sessions. She wore the same thing: leather pants, a silk shirt, a potent red lip. She’d sometimes use ‘fuck’ as a response to my stories, and she called the guy I was dating—the one I’d end up moving to Sweden for—‘the Swiss.’

Beverly’s daughter was a dancer. She had worked with Merce Cunningham, who I’d occasionally see, by then in a wheelchair. His company’s studio was on the 11th floor. Once, Lisa Oppenheim and I poked around up there and filmed on 16mm. She was humoring me. I thought I’d found an excuse for the analogue. Westbeth itself was analogue to the core—it originally housed Bell Labs, where early broadcast and communication technology was developed. In 1968 Richard Meier redesigned the building into affordable housing for artists, inaugurating the first work-live lofts in the country.

Neither the footage that we took then nor the pictures I’ve taken over the years ended up becoming anything. Some things resist being made into art, or art of a certain order—there’s just nothing more to fabulate. What takes hold instead is mere document.